OVER THE PAST century the district of Werd in central Zürich has developed into quite a hub for the Swiss media. The morning newspaper Tages-Anzeiger was first to claim their space in 1902 and since then many more companies have headed here to share in the creative climate that defines the area. The biggest news in the district right now is media group Tamedia’s seven-storey office building. The company’s employees were previously dispersed across various locations around Zürich. In January 2009, planning permission was granted for a new, larger headquarters designed by Shigeru Ban. This is the Japanese architect’s first building in Switzerland and the country’s tallest ever timber construction.

“Shigeru Ban was chosen as the architect because we see many similarities between his architecture and our business,” explains Christophe Zimmer, Head of Corporate Communication and Investor Relations at Tamedia. “Working for a media company means always having to come up with new ideas and be creative. And that’s also something of a signature for Shigeru Ban, who time and time again shows it is possible to be innovative, even with seemingly ordinary materials.”

The ground was first broken in August 2011 and by mid-June 2013 the newspapers 20 Minuten and Tages-Anzeiger were beginning to move their editorial teams in. The construction work was preceded by rigorous preparations involving some of Switzerland’s leading timber frame designers.

Christophe Zimmer puts Shigeru Ban’s choice of timber frame down to his previous collaboration with the Swiss engineer Hermann Blumer. He specialises in complex timber constructions and, together with Shigeru Ban, is able to look back on a number of prestigious projects, including the Centre Pompidou-Metz in France with its billowing timber-framed roof. Hermann Blumer was brought on board for Tamedia’s headquarters at an early stage.

“My task in our collaboration is to interpret Shigeru Ban’s architectural solutions and make sure they are technically deliverable. We don’t talk much to each other, communicating more via sketches and drawings. We also use the same CAD programme,” comments Hermann Blumer.

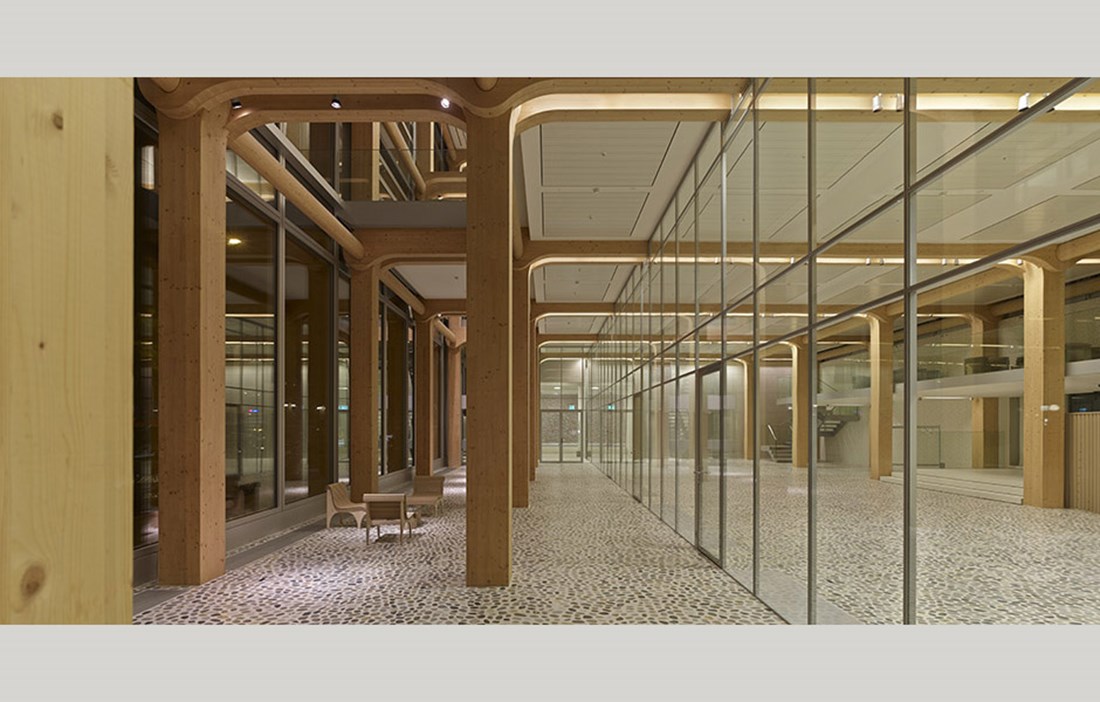

IT IS NOTICEABLE that the architect is not looking to dominate the cityscape with his building. It is far from discrete, and yet it melts into the existing built environment. The ground floor has double ceiling height, just like the surrounding properties. The mansard roof with its sloping sides also follows the lines of the other architecture nearby. What makes the building stand out is the enormous glulam timber frame. Instead of concealing the timber, Shigeru Ban leaves it fully exposed. The full glass facade also imbues the building with a level of transparency that a media group in particular would appreciate.

The timber construction is precision work with Hermann Blumer’s fingerprints all over it. It is designed as a framework of posts and beams prefabricated by the company Blumer-Lehmann in Gossau. Each frame weights 24 tonnes and comprises four 21-metre posts and five 17.5-metre double beams. The timbers were transported to the site by lorry at night for immediate assembly the next morning. Since there was no option to store the prefabricated timbers on site, there was also no scope for specification errors. The team assembled one frame at a time, with the previously erected frame providing the model for the next. The nature of the design meant the building did not rise up vertically, the way we are used to seeing new buildings take shape. Instead of aiming for the heavens, the carcase emerged more on a horizontal plane as the frames were connected to each other.

The structure has required a considerable amount of spruce timber, 2,000 cubic metres in fact, which amounts to around 3,600 trees. Shigeru Ban also specified slow-grown spruce with narrow growth rings from the same location, at least 1,000 metres above sea level. These conditions give the timber better properties than trees with a faster growth rate, including improved dimensional stability. With such large quantities required, the timber had to be sourced from the neighbouring country of Austria and the region of Steiermark, which has the nation’s greatest density of forest. The trees were harvested here and turned into glulam before being shipped on to Blumer-Lehmann, whose CNC milling machines created the 1,400 structural timbers.

The wood in the framework was delivered untreated and will remain that way.

“The best maintenance is no maintenance at all! Since wood is a living material, it will change over time and age gracefully, without us having to get involved,” says Christophe Zimmer.

KNOWING THAT SHIGERU BAN has done away with any hint of metal in the timber frame makes the building even more fascinating. But not one nail or screw has been used to join together the prefabricated timbers. Instead of steel joints, Hermann Blumer developed a special system using a large wooden peg in a harder wood – beech.

The tendency nowadays is almost exclusively to use screws and nails to join timbers. As a consequence, Hermann Blumer feels timber construction has lost something both technically and in design terms.

“That’s why it’s so exciting that Shigeru Ban has taken a step back and returned to the traditional methods of jointing without screws and nails. The idea of a beech peg might seem like a new innovation, but the system has actually been put to use before in manufacturing. Wooden pegs used to be employed to fix the bearings in place on rotating metal axles,” explains Hermann Blumer.

The architect made his choice out of a desire not to have any fittings interfering with the timber construction, but also a desire to use renewable materials as far as possible. This type of advanced joinery technology is reminiscent of traditional Japanese wooden architecture. In theory the framework could be disassembled and reassembled, without damaging the materials.

However, Shigeru Ban is not the only one focused on environmental criteria. Sound eco-credentials were required by the city of Zürich, whose population voted in favour of ‘the 2000 Watt Society’ in 2008. This is an energy policy model that shows how it is possible to only consume as much energy as the world’s reserves permit. The 2000 Watt Society places tough environmental requirements on industry, not least concerning material choice, energy consumption and climate impact.

Building a prefabricated timber building in the heart of Zürich city centre has been the greatest challenge, according to Christoph Zimmer, who also mentions having long conversations with the fire safety authorities.

“Since all the timber in the building is visible, we needed to install a sprinkler system. In addition, all the glulam timbers went through a separate inspection to ensure their load-bearing capacity in the event of a fire.”

TAMEDIA ESTIMATES THAT the total construction cost of EUR 40 million is around 20 percent higher than if they had chosen a more traditional building material such as concrete.

“We feel the higher cost is justified since our new headquarters put both Tamedia and Zürich on the map. A building like this shows we are a company that believes in the future. And of course, our staff deserve a good working environment that encourages them to be creative. The choice of wood plays a central role in this respect, with all its tactile splendour. Wood smells good, gives good acoustics and indoor climate and is also very easy on the eye.”

It is already clear that Tamedia’s headquarters are not the last mark Shigeru Ban will be making in Switzerland. Next in the pipeline is a commission for the country’s famous watch manufacturers Swatch and Omega, whose new headquarters in Biel will be completed by summer 2015.

Text Katarina Brandt