AMONG FINLAND’S DEEP spruce forests, moss-covered mountains and thousands of lakes, nature and myth merge in a unique way. In Finnish folk tales, God is called “Ukko” and is a kind of father-figure – but he is only one of many spirits in nature. The most sacred animal is the bear, whose name is said in a whisper so as not to disturb the magical creature. Birds are also sacred. According to myth and legend, they live at the world’s end, flying across the night sky and leaving a trail in the form of the stars in the Milky Way – before landing on a person’s pillow and awakening her soul while she dreams.

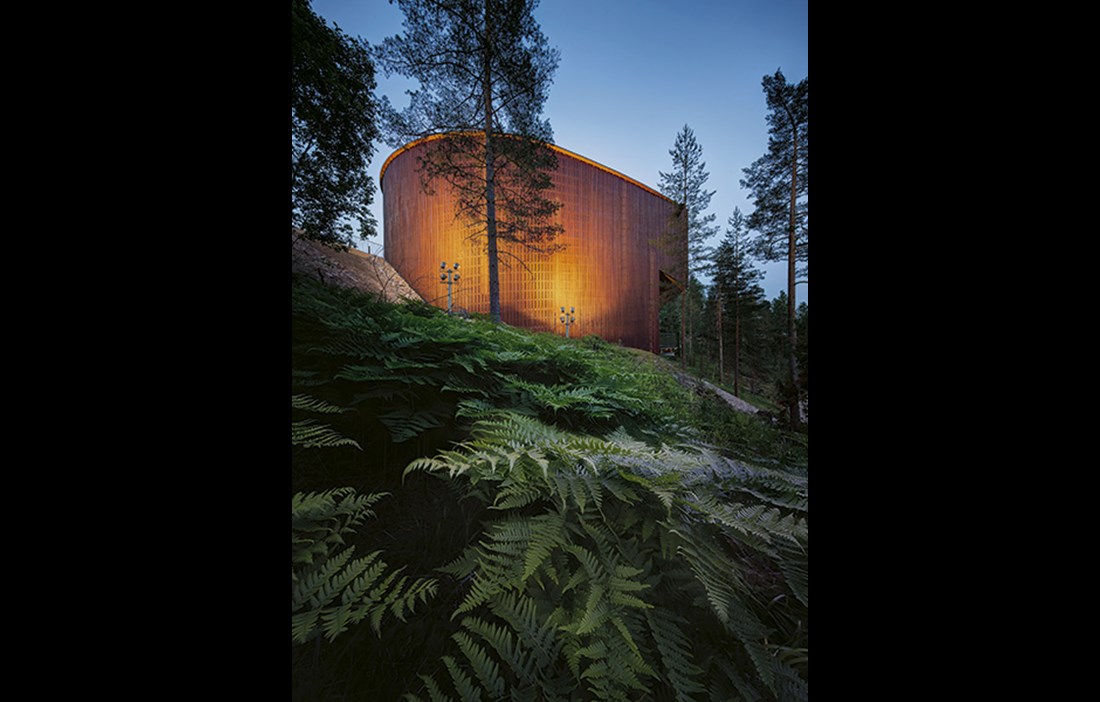

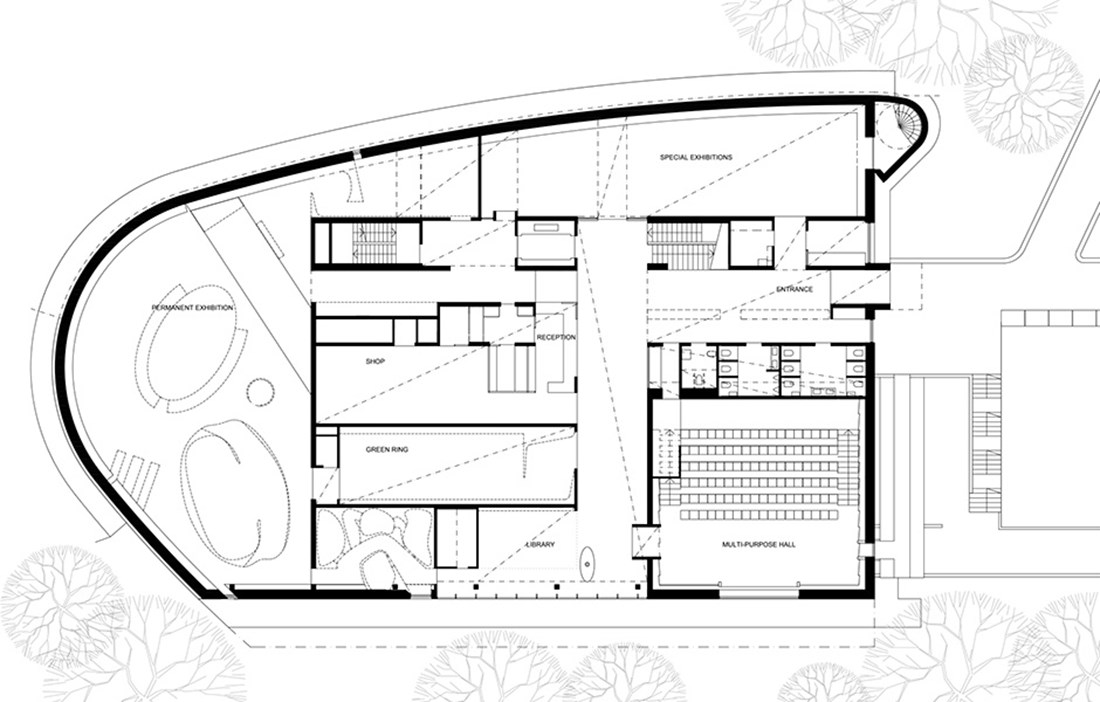

The key role of the bird in Finnish folklore was an inspiration in creating the Haltia visitor centre. When designing the building, Lahdelma & Mahlamäki took as their starting point the Finnish epic poem Kalevala’s saga about the duck that lays an egg containing the world. From a distance, Haltia looks like a huge brooding duck in wood that watches over the Finnish forests. The tower at one end is reminiscent of the bird’s neck. Inside the large hall in the building you can even see the mythical egg – here in a wooden structure that houses a video installation by Finnish artist Osmo Rauhaia. Since Haltia opened in May in 2013, it has held a collection of all the finest Finnish nature, from the archipelago environments in the south to the mountain peaks of Lapland, within easy reach of nearby Helsinki.

“Haltia serves as the headquarters for all Finland’s rural visitor centres. We have around 40 across the country, all with a focus on their respective geographical areas. However, most of them are in northern or eastern Finland and are relatively inaccessible. That’s why we built Haltia. The aim is to give visitors an insight into our stunning countryside and encourage them to go out and look at it,” explains Rainer Mahlamäki, chief architect on the project.

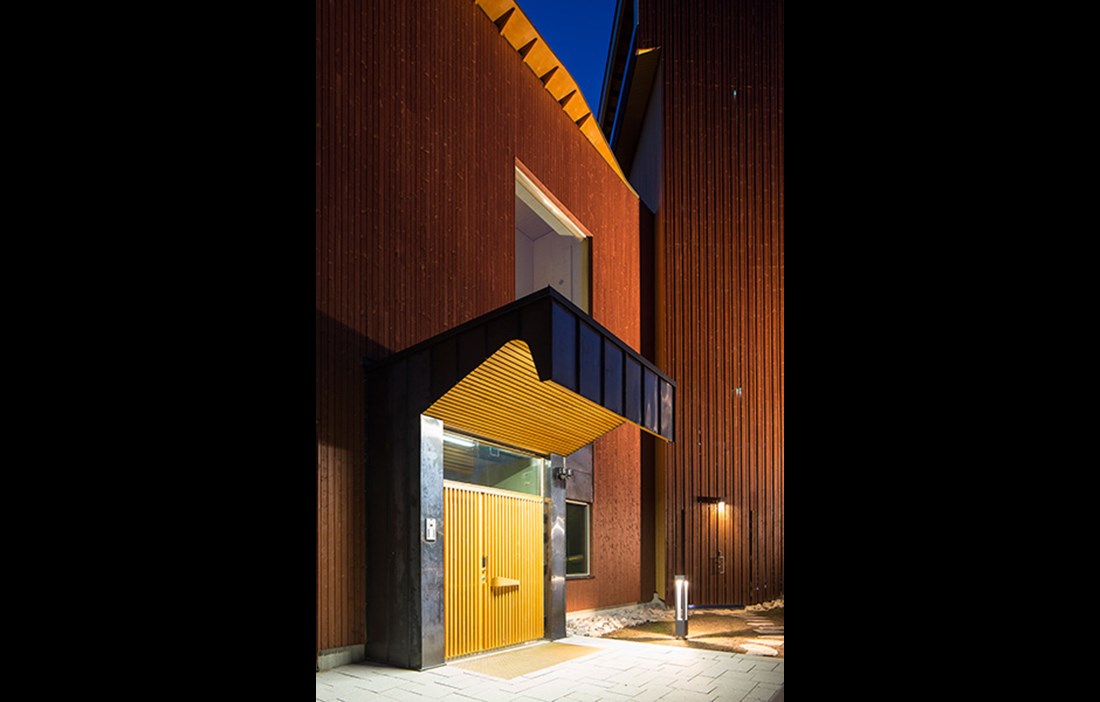

THE MAIN EXHIBITION at Haltia comprises nature films, photographs and an animated, soundtracked landscape panorama. The visitors also have an opportunity to experience a night walk in the Finnish wilderness, and visit a bear in its winter lair. As well as its exhibitions, the building has conference facilities, a restaurant, a café and an auditorium. Since Haltia sits on a 40-degree slope, the entrances to the different levels have been placed at different points on the hillside, creating separate entrances for each level. This also provides clever evacuation routes from the premises, which combine with a sprinkler system to meet the fire safety standards for a wooden building of this scale.

“The slope did impose some constraints on us, but for an architect that can often form a creative starting point. The only real problem with the slope was that we were forced to limit the use of wood to a certain extent, since the sloping ground required concrete to stabilise the building,” says Rainer Mahlamäki.

APART FROM THE ground floor, where some concrete had to be used, Haltia is a building made entirely from wood. The whole visitor centre is constructed using prefabricated cross laminated timber (CLT) in spruce that was manufactured in Austria. The strength of the material means that there is no need for structural posts or beams. The panels were delivered in 4 x 16 metre pieces of varying thicknesses, which were then customised by a Finnish company in Pälkäne before being shipped to the site. The building is the first in Finland to use this type of CLT throughout – from the structure to the facades, to the ceilings and floors. Haltia’s inspiring use of wood helped it to win last year’s Finnish Wood Prize. However, using wood to this extent has not been possible in Finland until very recently.

“We designed a visitor centre in the forests of Punkaharju in the early 1990s, a kind of museum relating Finland’s history with wood. Ironically, we were forced to build it largely out of concrete, since the fire safety regulations of the time made it very difficult to build in wood. Fortunately, things are very different today.”

Spruce was used in part because it is a relatively light material, which would make the whole construction process easier. Using the same material throughout the building also gave Haltia a coherent feel. The dark-brown tones of the facades are the result of a process where the wood is heated under pressure – and treated with silicon dioxide vapour – to kill the cell structure and make the material more resistant to sun, damp and rain.

“Just like many other architects, we tend to avoid treating wood in any way. Not even painting it. It looks so good as it is. But the idea of this building is that it will stay looking the same over time, which is why we used this technique.”

Energy efficiency is an important part of Haltia’s philosophy. The aim is for the groundbreaking eco-technology to inspire – and serve as a model for – climate-smart technologies. Standing up in the viewing tower, there are equally good views of the lake and the carbon-capturing grass roof, as well as the building’s solar panels immediately below. Haltia is largely self-sufficient in heating through solar energy and an extensive geothermal energy system, with 11 kilometres of piping drilled into the rock. The system supplies heating in winter and cooling in summer. A lift was essential in the building, but it was located for the smartest use – by staff and visitors alike. Haltia’s terrace at the back overhangs a large picture window on the floor below and therefore provides shade and cool in the summer. The partly rounded facades reduce the wall area and are thus better at keeping the heat in and the cold out.

HALTIA IS LOCATED a couple of kilometres outside Noux National Park, but is still surrounded by the key components of the Finnish countryside: forests, mountains and lakes. The building is designed to sit naturally in its setting, as expressed in the choice of materials and design. At Haltia, strict rectangular shapes meet a freer, more curved design, symbolising the structured human world meeting the natural world. The hill rises north of the building, giving Haltia the impression of huddling up and seeking protection from the Finnish dark and cold. To the south, the tower faces out towards the lake, the open landscape, light and warmth.

“Finnish design often tends to stand in dialogue with its surroundings. The harmony can be felt and seen, and Haltia couldn’t be transferred to any other country, or indeed any other location in the Helsinki area. The fact that the building is made in wood reinforces the Finnish, perhaps even Nordic, feel. In Finland, there is a strong tradition of building in wood, which we’re continuing.”

Text Erik Bredhe