ANYONE WHO HAS been out into the countryside on the Swedish island of Gotland will no doubt have noticed that many of the buildings have a wooden roof. Timber boards have been a common roofing material on many different types of building – not only on Gotland but across Sweden.

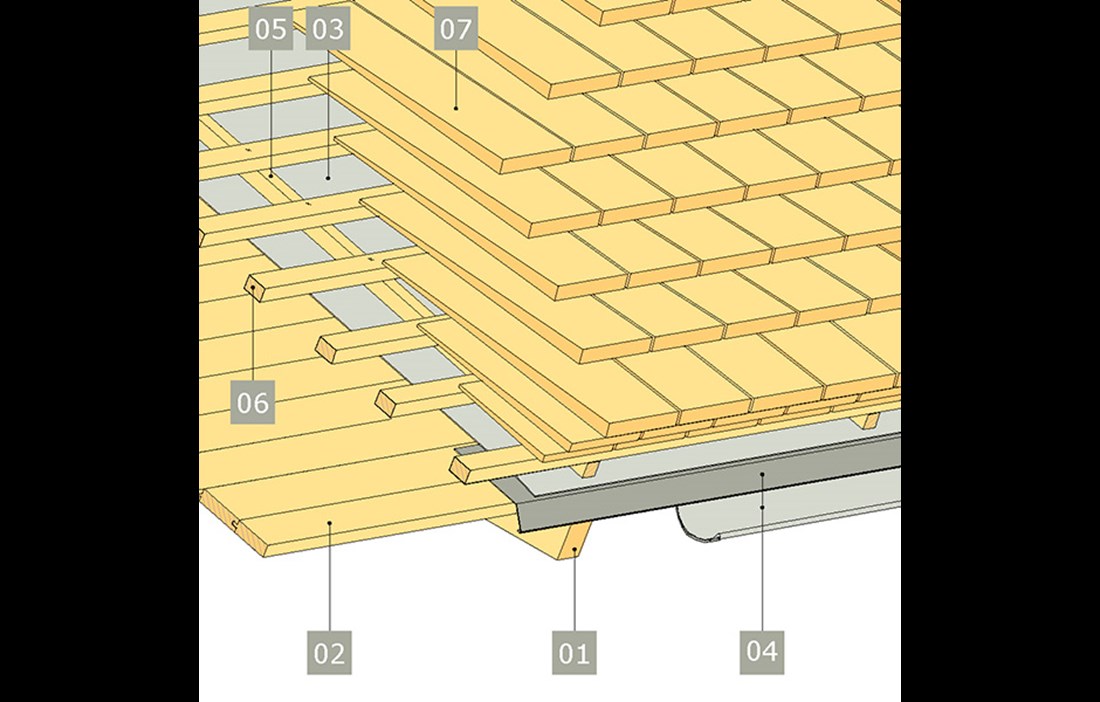

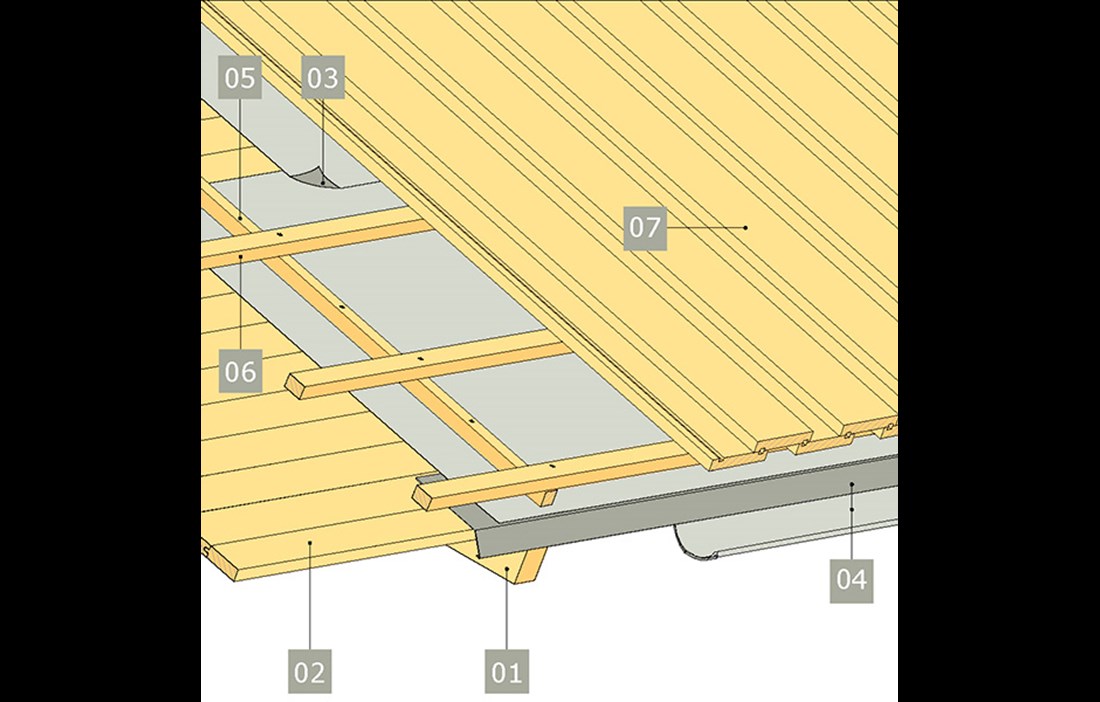

A board-on-board roof comprises a double layer of vertical boards that follows the fall of the roof. Some roofs have two or three drainage grooves in the boards, and there are numerous variations in roofing technique. The roof is constructed so that the boards tighten up against each other when they bow. The boards are installed heartwood side up, and the underlayer of boards should have drainage grooves in the upper side. The roof is constructed so that it can be aired and any moisture can run off or be ventilated away.

The boards used for this kind of roof have traditionally been heartwood pine that is treated with pine tar every few years. Today there are a range of options for anyone wanting a board-on-board roof, including impregnated pine (wood preservation class NTR/AB), larch heartwood or western red cedar.

The lifetime of a board-on-board roof in impregnated timber is estimated at around 30 years, while the figure is slightly shorter for pine or larch heartwood and longer for impregnated timber that has also been treated with oil. The lifetime depends on the workmanship, location and maintenance.

One benefit of the board-on-board roof is that it does not need replacing in its entirety. If damage is found, only the damaged boards need to be replaced.

ARCHITECT ANDERS LANDSTRÖM grew up in Norrbotten and has a special relationship with wood. Using wood in construction and interiors is a signature for both him and his practice Landström Arkitekter.

“Wooden roofs bring something extra to a building,” says Anders. “It’s often a particular aesthetic, a way of connecting with nature or an older building.”

Landström Arkitekter has chosen wooden roofs for several of its projects. A summer cottage on Lisslö in the Stockholm archipelago was topped with a boarded roof in heartwood pine, for example. And the children’s zoo Lill-Skansen, which was completed in 2012, also has boarded roofs in flame retardant heartwood pine on several of its buildings.

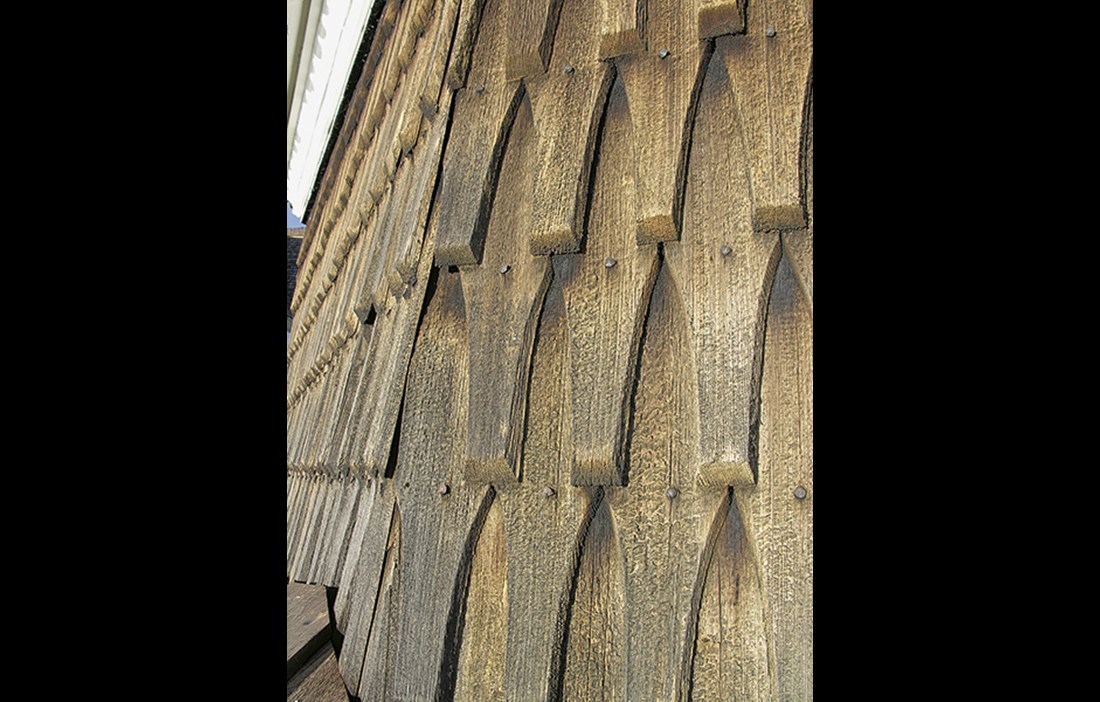

SHINGLE ROOFS ARE another type of wooden roofing that has a long tradition in Sweden. The oldest wooden tiles are the thick shakes that were split by hand and often used on churches. Pine shakes from the 12th century have been found on Skaga stave church in Västergötland.

Wooden roof tiles come in two varieties, shakes and the thinner shingles. Shakes are thicker, tapered tiles in pine, spruce or occasionally oak. They are usually 450 millimetres long and the width should be a third of the length, so around 150 millimetres. Western red cedar and larch shakes are also available, as is impregnated wood (preservation class NTR/AB). The wood should be straight and knot-free.

These days, shakes are made mechanically with one sawn and one split surface, with the split surface always facing upwards. The shakes are usually laid over 20 millimetre sheathing and underlay felt (grade YAP 2500). Roofs made from shakes have to be regularly treated with pine tar. Tarred and well maintained shake roofs can last 100 years or more.

SHINGLES ARE THINNER, at 3 – 7 millimetres thick. The length varies, but is usually 400–600 millimetres. Shingles can be split, planed or sawn. They should be laid over a well aired underlay and are ideal for houses with an uninsulated roof or an unheated outbuilding. Shingles can often still be in place under a more recent tiled or metal roof.

Shingles are sometimes impregnated, dipped or boiled in a solution of water and iron sulphate. They may also be painted red, but they are usually left untreated.

The high-rise apartment blocks in Sundbybergs Strandpark, designed by Wingårdh Arkitektkontor, have facades and roofs clad in shingles, with the wood taking on a lovely patina in the sun and rain. The Western red cedar shingles have a finely sawn surface and provide natural resistance to wet and dry rot. The supplier Moelven Wood reckons that these untreated shingles will last a good 50 years.

But how can more people be persuaded to choose wood as a roofing material? Anna Pousette, researcher at SP Trä, the wood division of SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden in Skellefteå, believes the key is to spread information and knowledge – promoting good examples that show how well it can work.

“Increased demand would have several positive effects, including a better range of products from good raw materials. That’s essential for the durability of the roof.”