ACCORDING TO UNESCO, the impressively expansive mountain landscape of Laponia and its well preserved cultural capital constitute “the largest area in the world (and one of the last) with an ancestral way of life based on the seasonal movement of livestock.” The area has been populated by the Sami since prehistoric times, and has been a World Heritage Site for 18 years. The Sami tradition has shaped the landscape, with reindeer husbandry setting the tone. Now the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency has created a dedicated visitor centre here, in the middle of Stora Sjöfallet National Park. The educational centre is intended to inspire fun and discovery by providing knowledge about the landscape, and also – primarily – generating an understanding of Sami culture.

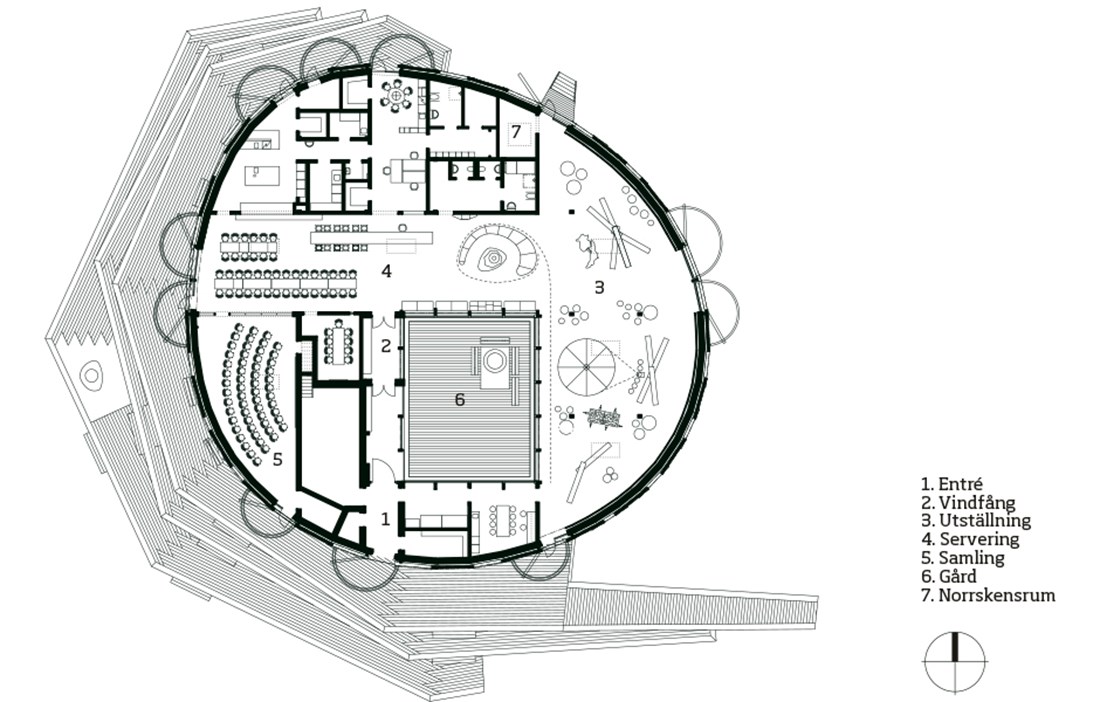

The site was chosen by the Sami community of Unna Tjerusj, but the Swedish state only has the land on loan. The visitor centre is almost a force of nature in itself. The round building sits tentatively on the rock, resting on 90 supporting plinths. The shape was chosen by the chief architects from Wingårdh Arkitektkontor for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

“I knew that rounded shapes are popular in Sami culture. The building also stands in the middle of a reindeer herding route. If it is going to have several thousands of reindeer passing by, we needed to make sure there were no corners or other protruding parts where they could get stuck,” says architect Gert Wingårdh.

Solid pine heartwood beams are stacked around the whole of the well insulated core, given the impression of a trellis. The wide gaps in between will trap snow and make the frozen precipitation part of the facade. It is not for nothing that the building is called the Snow Trap. In just a few years, the pale yellow wood will have silvered.

“We want the building to melt into its natural surroundings. It is quite big, and yet somehow scaleless. The sleekly rounded shape is deceptive. Everyone’s surprised that the building is so big inside. The design language is timeless. Looking back, it will be by no means obvious that this was designed in the 2010s. It could just as well have been built in the 1960s or 50 years from now,” states Gert Wingårdh.

THE ARCHITECTS CAME up with the idea of placing the building in the open landscape, where it is most exposed to the might of the weather. They noted that there were fewer mosquitoes out on the plain than nearer the forest. It does, however, place the building in one of the windiest locations in Sweden. In winter, wind speeds often reach in excess of 15 metres per second. In fact, winds reached 60 metres per second once during the building’s construction.

This prompted the inclusion of an atrium courtyard, which can provide shelter from the wind and at the same time help to capture the snow. On the windward side of a building, the snow blows away, but on the leeward side the wind loses its energy and the snow drops down. The architects hope to achieve this effect in the atrium courtyard, so that it fills up with snow, which will then remain long into the spring as a reminder of the extreme winter climate.

A sloping hipped roof leads down towards the atrium courtyard, where there is a fire pit to gather around. The idea has been to capture the drive to seek shelter, rather than creating a building with big panoramic windows overlooking the surrounding countryside.

“The interior is very inward looking and dark. Like an abstracted Sami tent , but on a different scale,” relates Gert Wingårdh.

Much of the 950 square metre Snow Trap is made of wood. The roof comprises primary beams of 700 millimetre glulam and a secondary structure of 360 millimetre plywood beams with insulation in-between. The roof is then supported by a wooden structural frame. Transverse beams and braces in the partition walls give the structure strength and rigidity. The outer layer of the roof is finished in roofing felt.

Building in wood was an obvious choice. Partly because so much of Sweden’s wood grows up here in the north. And partly because the wood structure is seen as easy to disassemble and carry away. This fulfils a condition of the project stating that the land will one day be returned to the Sami people, with as little effect on nature as possible.

It should not require masses of vehicles and cranes to take the building down.

“The facade is stacked so that it looks like it can be taken down by two people, and erected somewhere else. We felt this was a desirable effect,” says Gert Wingårdh.

There has been little in the way of groundworks. With the building raised on plinths, there is no need for drainage. And visitors heading from the building out into the surrounding pine forest proceed along raised wooden walkways, designed by Andersson & Jönsson Landskapsarkitekter, so as not to damage the fragile lichens on the ground.

INTERNALLY, VISITORS ARE led past the atrium courtyard into increasingly impressive rooms, which meet the sometimes heavily and sometimes gently curved outer wall. The reception has a café at one end and an open fire at the other. In the observatory, one window rises upwards so that visitors can marvel at the stars in the night sky.

The interior too is dominated by wood. The original idea was in fact to have concealed plywood beams, rather than the visible glulam structure. The whole building was also going to use textiles inside and out. However, uncertainty about this approach led to the current, tried and tested design. Fabric would probably have been used to create the ceilings. Gert Wingårdh is pleased with the result. There was no friction in the collaboration with the clients, the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and the County Administrative Board, and the contractor Nåiden Bygg worked exceedingly hard, often in very difficult conditions, to realise the vision.

GERT WINGÅRDH IS particularly pleased that the Sami have taken the visitor centre to their hearts, so it looks like it is going to be a proper Sami centre. There is a good chance that the Snow Trap will be a lasting feature in Laponia. It is certainly robust enough.

“It survived the storm, with its winds of 60 metres per second. The thick beams on the facade wear by just a few millimetres per year, giving an expected lifetime of several hundred years.”

Text Johan Bentzel