THE LIGHT WEIGHT. The formability. The suitability for large spans. There are many reasons for choosing wood when building a roof, according to Roberto Crocetti, Professor of Structural Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering, Lund University. He has also been involved in establishing construction company Limträteknik’s new office in Malmö, which opened in September. Roberto Crocetti has noticed a growing interest in wood for large roof structures. This is true not least in countries where wood has historically not been as popular as in Sweden.

“Many architects realise the freedom that the material offers. Wood is relatively cheap. Another benefit in roof structures is that wood can stretch over large spans. I’d say it’s one of the best materials in terms of its strength to weight ratio.”

However Roberto also sees challenges. Wood is a living material that moves. As a structural engineer, it is crucial to predict the movements that might causes stresses. And this is particularly important when designing joints in wood.

“You need to have a feel for the material, to know how joints should be worked out and to protect the wood from the elements, either with various surface treatments or by enclosing the parts that are exposed to moisture. That way, the structure will last and last.”

Another thing promoting increased use of wood is the interest in sustainability issues. This has long been a determining factor for Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. In April 2014, he was awarded the prestigious Pritzker Prize, often referred to as the Nobel Prize of the architectural world, whose purpose is “to honour a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which have produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.”

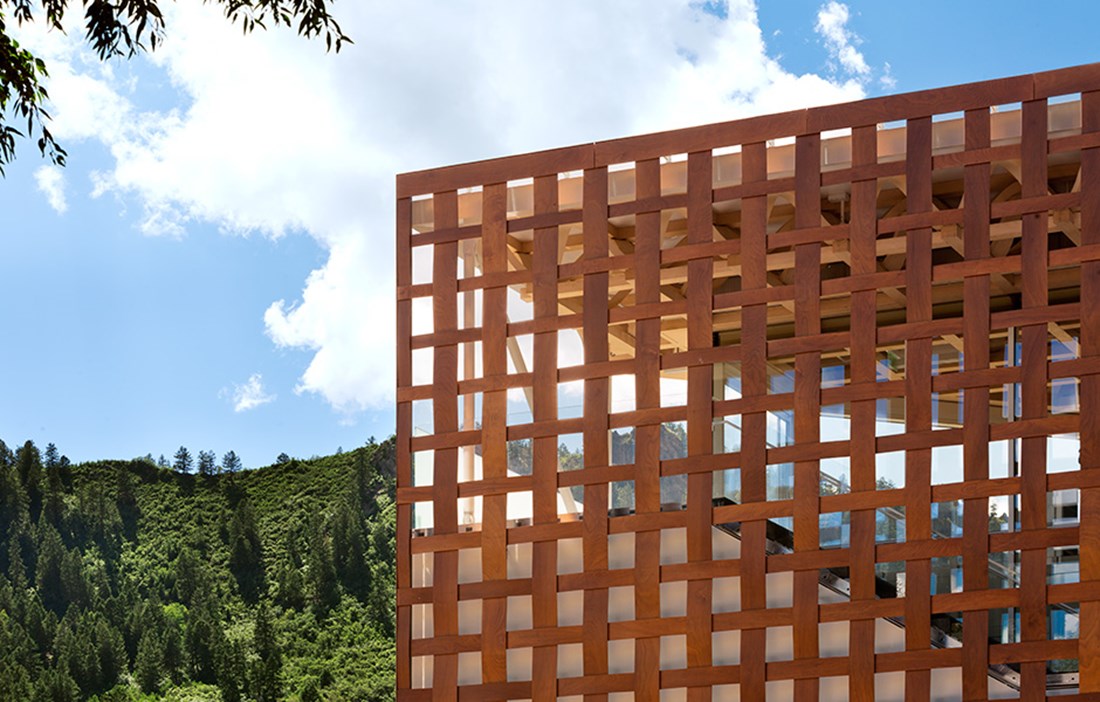

ONE OF SHIGERU BAN’S latest projects is Aspen Art Museum in the US state of Colorado. The new museum, which opened in August, may not have the same spectacular exterior as many of Ban’s previous international landmarks, such as the Centre Pompidou-Metz in France, with its billowing wooden roof. However, Aspen Art Museum remains a building that is in many ways typical of Shigeru Ban – not least when it comes to the roof structure.

The architect was initially unimpressed by the chosen location for the new museum building. Having climbed up onto the roof of a nearby building, he then realised that the site was not bad after all. From the roof of the building, he was able to look out across the rocky, tree-clad mountains and the many long pistes of the ski resort.

The experience led him to reassess the way visitors would approach the museum. Instead of placing the entrance on the lower floor and then continuing the movement upwards through the building, Ban did the reverse. The entrance is located up on the building’s roof terrace and is reached via an external staircase or glass lift. From here you not only get a wonderful view, but also a glimpse of the impressive roof structure.

Shigeru Ban believes that the upward movement is particularly suitable for a place such as Aspen. In many ways, it calls to mind the sport of skiing, an activity that has made the resort famed the world over. Skiers take a lift up the slope, enjoying the view, before heading down one of the pistes.

Half of the roof terrace is covered with a glass roof, which is held up by a glulam structure. After this flourish, Shigeru Ban takes a more measured approach on the floors below, with the architecture being consciously restrained so as not to compete with the art on display.

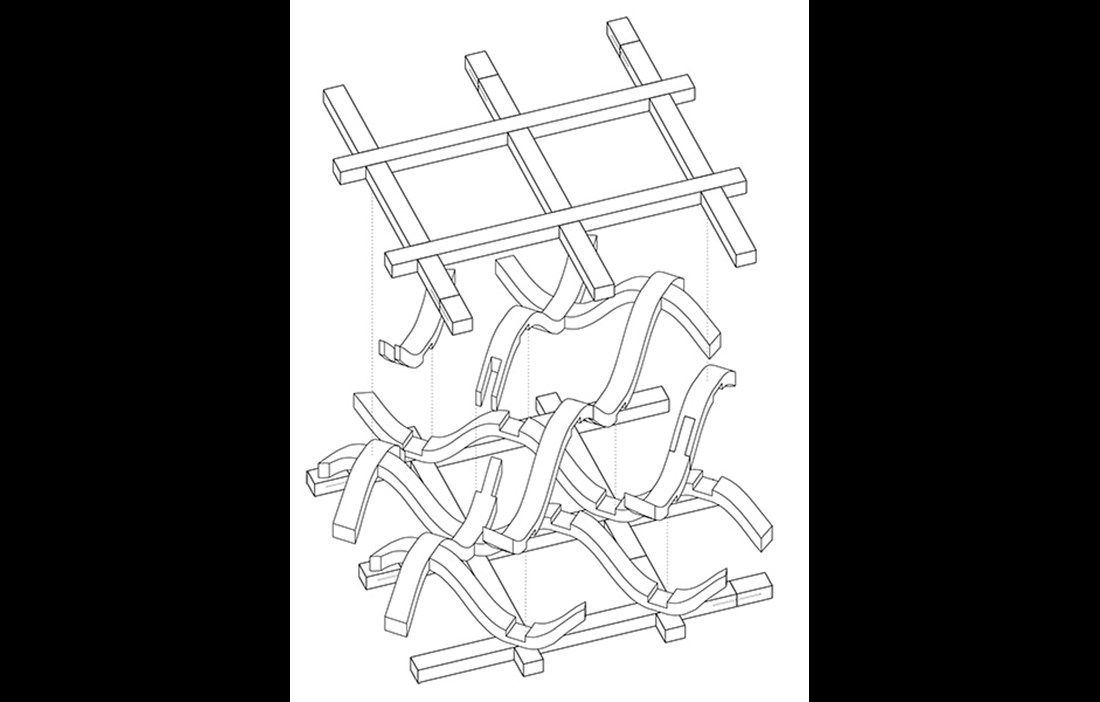

As with many of his projects, he has chosen to work with the Swiss engineer Hermann Blumer, who specialises in complex wooden structures. The result is a fusion of architecture, technology and three-dimensional modelling.

The roof is made of glulam that is shaped into undulating waves. No metal ties have been used, due to the architect’s wish to use renewable materials as far as possible. The Canadian company Spearhead Timberworks applied advanced CNC technology and huge precision to shape the curved glulam beams and ensure an exact fit, so that the elements locked into each other. The rolling waves of wood provide an exciting shadow play and depth on the terrace under the roof.

This type of advanced joinery technology is reminiscent of traditional Japanese wooden architecture. In theory the framework could be disassembled and reassembled, without damaging the materials.

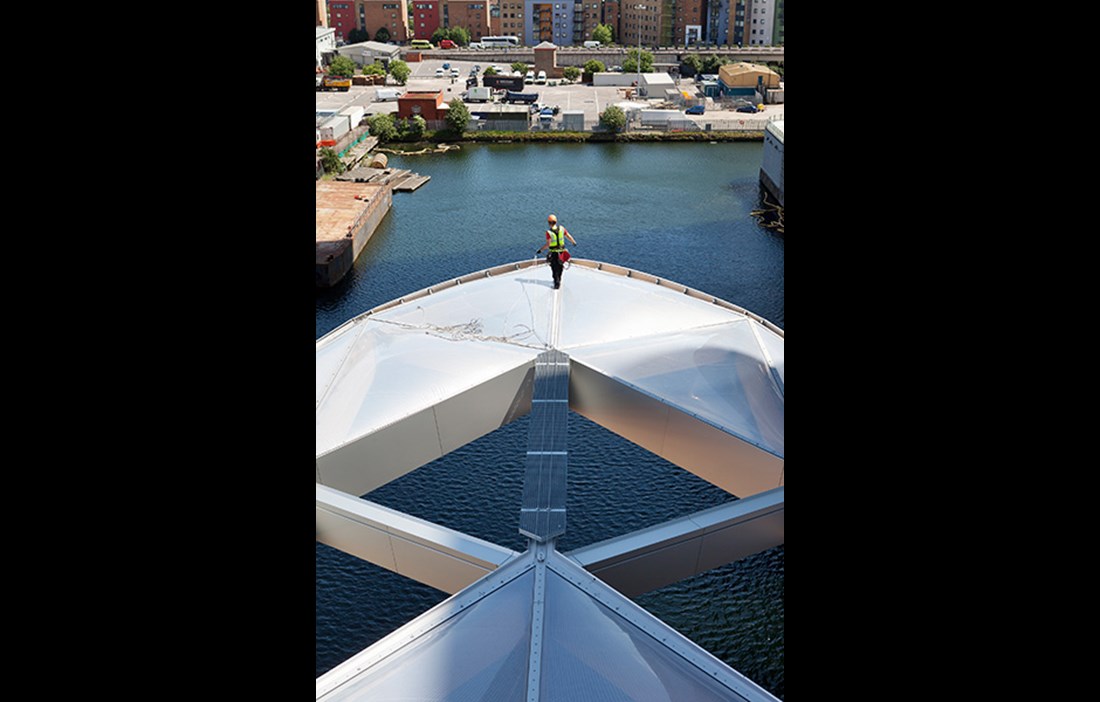

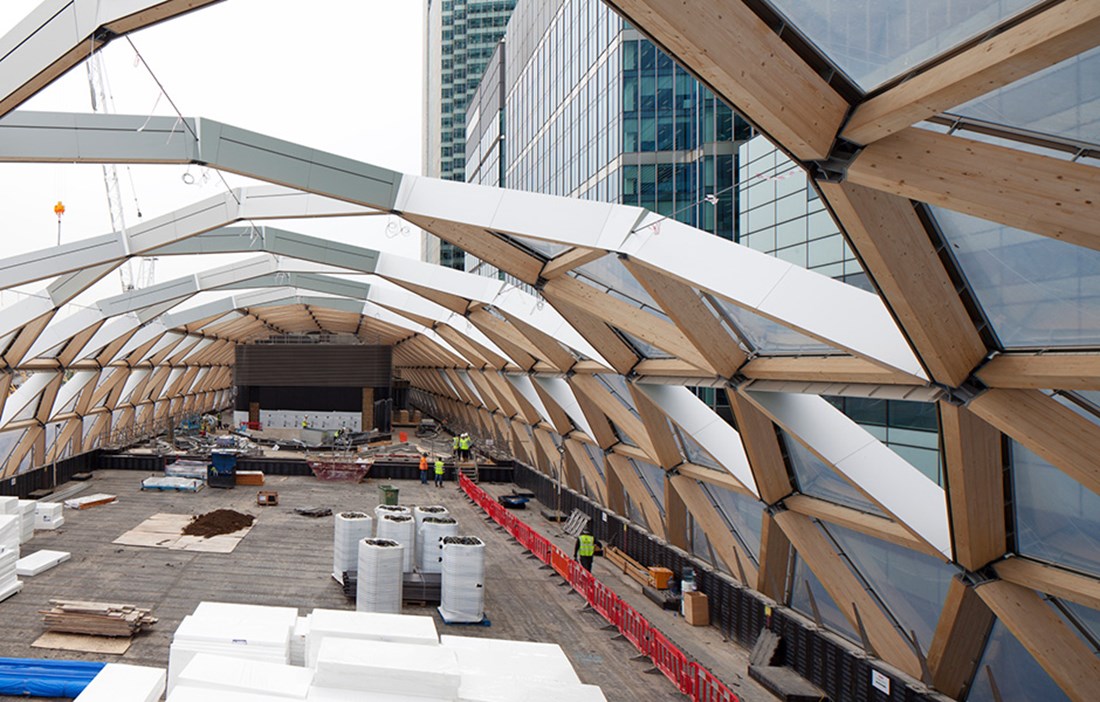

IN DOCKLANDS, just outside the centre of London, Canary Wharf Crossrail Station sits like a ship in dock. The building is wrapped in a 310 metre glulam structure – a gigantic cover that makes up both the facade and the roof. The combined station building and retail centre was designed by Foster + Partners. The final parts are now being completed ahead of the approaching inauguration in spring 2015. The building reflects the area’s past as a centre for the UK’s global merchant fleet. The site is now being integrated into London’s cityscape and the growing commercial district of Docklands.

The initial work began back in May 2009 with construction of the dock that allowed the creation of the four storeys 28 metres below the water.

The glulam structure is protected by transparent air cushions in self-cleaning EFTE plastic. The cushions are fixed with aluminium strips to the underlying triangular beams. Despite the curved shape, the structure only makes use of four arched glulam beams.

“The glulam frame provides a warm and natural counterpoint to the surrounding buildings in steel and glass,” says Ben Scott, architect at Foster + Partners.

“Wood is natural, sustainable and welcoming. It’s also relatively simple to shape the material to follow the roof’s complex geometry.”

On the top floor, closest to the roof, there will be a botanic garden. This is made possible thanks to the EFTE plastic in the roof, which creates the perfect microclimate for growing. The idea is that the garden will contain a selection of the tropical plants that once reached the UK via ships mooring up at Canary Wharf.

“We’ve left the roof structure open in places, partly to let light in, but also for natural irrigation from the rain.”

THE RIVER NECKAR that flows through Neckartailfingen, 25 kilometres south of Stuttgart, is a major influence on the German municipality. It has, for example, lent its name to the new Neckarallee Festival Hall which opened in 2013. Ackermann + Raff designed the building, whose wooden roof structure roots it firmly in its surroundings.

“The idea was to recreate the sense of walking along the nearby riverside promenade, Neckarallee,” explains Julia Raff, architect at Ackermann + Raff.

“We were inspired by the pattern formed when branches and twigs overlap each other. Realising the idea in wood seemed like an obvious choice.”

The roof stretches over the building in a diamond grid. Internally, white lacquered birch plywood fills in each diamond. The panels help improve the acoustics and have been placed at different angles to create life and movement. The surrounding areas of glass accentuate the roof’s sense of lightness.

“The light roof structure has allowed us to keep the large assembly hall and the overhang outside the entrance free from supporting pillars,” says Julia Raff.

Externally, the roof is clad in fibre cement panels. All the visible wood is treated with a glaze. In the overhang outside the entrance, some of the diamonds have been left open to let in light from above.

Text Katarina Brandt