Together, Roberto Davolio and March Brulhart have spent the past five years developing new ways of building in wood. Based in Hong Kong, their preferred choice of material is highest quality pine from Swedish forests. A keyword in their work is communication.

“When you work in steel, you get a catalogue of steel beams and so on, combine standard parts from various multinational companies and it moves on to the next consultant. Everything is measurable and calculated, there is no great need for communication between the different teams. But with wood you have to build a trusting relationship between the various parties involved in the project. Wood allows us to apply a very different design process, based on quality relationships,” explains Roberto Davolio.

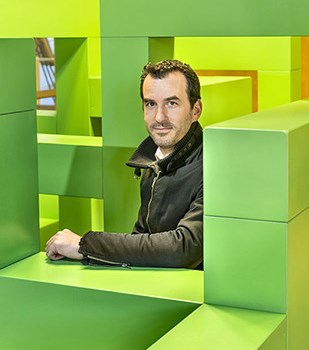

Awawa’s in-house system is based on joining wood without any use of metal. As far as they are concerned, wood in outdoor environments should not contain screws. “Screws screw up the wood,” is how Marc Brulhart puts it. He takes two sample pieces out of his briefcase – they are joined lengthways with an advanced mortise and tenon system that clicks together with exquisite precision.

The reference to the traditional woodworking joints used in Japanese temples, amongst other places, is striking. But these two pieces of wood are the result of extensive product development over many years, covering every angle and curve.

“We made hundreds of joints and then began breaking them apart, to see exactly where they broke and how,” says Marc Brulhart. He points out a little extra feature at the tip of the tenon.

“This helps us enormously during assembly! Without it, these pieces wouldn’t stay together until they were fully fixed in place. This little feature helps with the adjustment of pieces that can be several metres long.”

The ultimate goal is to create a ‘library’ of joints that can fulfil different functions in a building. So far, Awawa has completed a number of small-scale, almost sculptural designs, including one for a furniture chain in Japan. However, the technology is strong enough for large-scale applications, and the skeletal structures could be clad in façade materials and panels. The designs are drawn on computers and individual pieces are then manufactured using a triple axis CNC milling machine, in a process that is almost entirely automated. The pieces then have to undergo a great deal of careful finishing before they can be assembled.

The structures should not need surface treatment of any kind. Instead, Awawa is keen to use the naturally durable heartwood of the pine. Today it is possible, back in the sawmill, to sort out logs with particularly large areas of the red heartwood and saw planks with natural durability.

“Many long for a return to things they can understand and react to instinctively. It’s just like with food, people want to know where it comes from, where it was grown. We want to do the same thing with buildings and reconnect with the material’s history,” says Marc.

And what about the name Awawa – where does that come from?

“Awawa!” cries Marc, “it’s the first thing you say when you enter the world!”

“We wanted a name that was elemental, emotional, but didn’t mean anything. It provokes an emotional reaction that we can then explain,” adds Roberto.