DRANCY IS A suburb of Paris plagued with social problems. The area is also stigmatised by its own history: during the Second World War, the German occupying forces set up an internment camp here. The housing stock largely comprises low-rise buildings built on former farmland. The municipality had spent years planning for a new gymnasium, but nothing ever came of it. When the task of realising the plans finally went to architect Alexandre Dreyssé and his colleagues, they wanted to help give the neglected suburb a new start – and a new sense of dignity.

Alexandre Dreyssé was born in Strasbourg and comes from a family of architects. He is the fourth generation to go into the same profession. His father, Henri Dreyssé, made a name for himself in the 1980s with a number of large wooden structures, including two residential buildings in Alsace. Alexandre Dreyssé trained in Paris, where for a while he also worked for the Cuban architect Ricardo Porro, before setting up his own practice. Dreyssé took his inspiration for the gymnasium, named after French basketball player Régis Racine, in part from the covered markets of the 19th century such as La Halle Secrétan and Baltard in Paris. But there are also influences from 20th-century Swedish architects Sigurd Lewerentz and Ralph Erskine. Another inspiration for the project was the work of British architect Edward Cullinan.

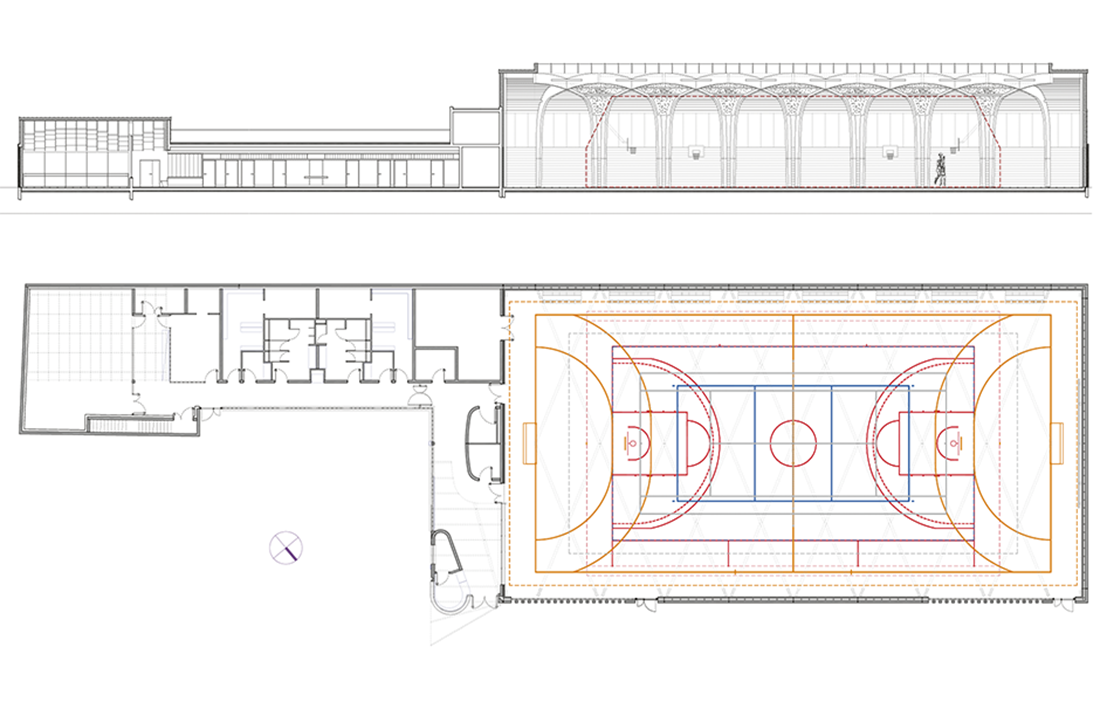

TODAY RÉGIS RACINE is used primarily by local schools and sports clubs. The sports hall itself is optimised for regional basketball tournaments, but the building also houses a studio for ballet practice. The impressive vaulting and seven metre ceiling height make it hard not to think of a Gothic cathedral – even if the arches are glulam beams rather than sandstone.

There are several reasons why they chose wood, according to Alexandre Dreyssé. Firstly, there was the huge roof span: with an area of 44 by 22 metres, glulam beams were the only reasonable option. Building in prefabricated wooden modules also brought less inconvenience to the neighbours in a densely populated area. And when the client, the local municipality, expressed its desire for the building to use a durable natural material, that really sealed the deal. In terms of the building’s appearance, the character of the site also guided the architects – not least the fact that the façade is almost entirely surrounded by other buildings.

“Getting daylight into the building was a challenge,” says Alexandre Dreyssé.

The solution was opaque glazing integrated into the roof structure. To cut down on weight, polycarbonate plastic with insulating air channels was used. It was also easy to adapt to the arched shape of the roof. The fact that polycarbonate plastic is cheap was a bonus.

“A simple and honest solution, a bit like a potting shed!”

The parts of the façade that are visible contain double-glazing. The material provides sufficient insulation most of the time, but when it gets really hot outside, it can get a bit warm inside too, explains Alexandre Dreyssé. And since only a small section of the façade is visible from the outside, the main focus was on the interior.

“The building became kind of inverted – we invested in high quality on the inside!”

The overall design then emerged from studying a number of simple paper models.

“We didn’t really have a particular vision of what we wanted to do, instead we looked at what was appropriate for the site. The vaulted ceiling came about because we didn’t want to build too high a structure next to the neighbouring low-rise housing.”

THE COMBINATION OF WOOD AND BLOCKWORK has become something of a signature for Dreyssé’s practice. But again, the geographical location of the plot came into play. It faces a number of other properties – erecting scaffolding on the outside would have required negotiations with a long list of property owners. Construction started with a cast concrete slab and then the building was erected ‘from the inside’. The lower section comprises 20 cm thick, prefabricated concrete blocks that were left untreated on the outside. Once the block walls were up, the builders could carry out all the woodwork within the cordon set up around the site.

ON THE INSIDE, the dividing walls are built from the same concrete blocks as the exterior, although half as thick. Between these are sections of wood using a traditional stud system and an unpretentious cladding of OSB panels.

“Since the building is in a suburb with a history of social problems, we wanted durable materials that could take rough treatment.”

The choice of materials such as blocks, wood and plastic helps to create a horizontal impression on the outside. The standing seam metal roof is also extensively punctuated with sections that admit light. By studying the models, the architects found that the ceiling would look much more exciting if the arches were crossed over each other. Most of the daylight comes from above, creating a natural centre inside the sports hall.

“You could say it feels like a cathedral, but it wasn’t a look we were intentionally trying for. It was more a consequence of our work with the models,” states Alexandre Dreyssé.

“It was actually quite a simple and intuitive process. But structural wood engineers Tec Bois, who specialise in this kind of thing, were also a great help. The engineers showed huge respect for our architectural principles. They were the ones who made the project possible!”

In line with the Functionalist ideals that inspired the project, all the technical installations were left uncovered: electricity, heating, water and waste – everything is completely exposed beneath the ceiling.

“We didn’t want to hide things in ducting. It was a choice that also led to a good partnership with all the different trades – we showed that we value their work!”

There is also a Functionalist edge to the part of the building that is fully visible from the street. The daringly curved surfaces work with the façade material – Douglas fir, or Oregon pine as it is also known – and here again spruce glulam beams provide the structural frame.

THE HUGE, SELF-SUPPORTING ROOF STRUCTURE was put in place with the help of a scissor lift and a crane, one piece at a time. Each arch comprises four prefabricated sections which were made by a company in Alsace and transported to the site. The material is spruce grown in the Vosges region of northern France. The sections are held together with bolts and angled metal fittings. These fixings have been made invisible as far as possible. Alexandre Dreyssé has no idea what this mass of glulam beams, bolts, polycarbonate plastic and metal roofing actually weighs.

“Although it would probably be good to find out.”

TEXT: Mårten Janson