CHILDREN WHO ARE taught close to or in nature are more receptive to knowledge. They are also calmer, more creative and alert. Teachers also feel a different commitment in surroundings close to nature, which in turn gets passed on to their pupils. This was the conclusion of extensive studies presented recently in a major article in the Huffington Post. The French town of Rillieux-la-Pape, just north of Lyon, is home to the Paul Chevallier school, which in many ways encapsulates the very green, stimulating school environment that the article describes. Adjacent to leafy Parc Brosset stand a couple of impressive wooden buildings that are as like a school as they are something from the classic fantasy tale Lord of the Rings.

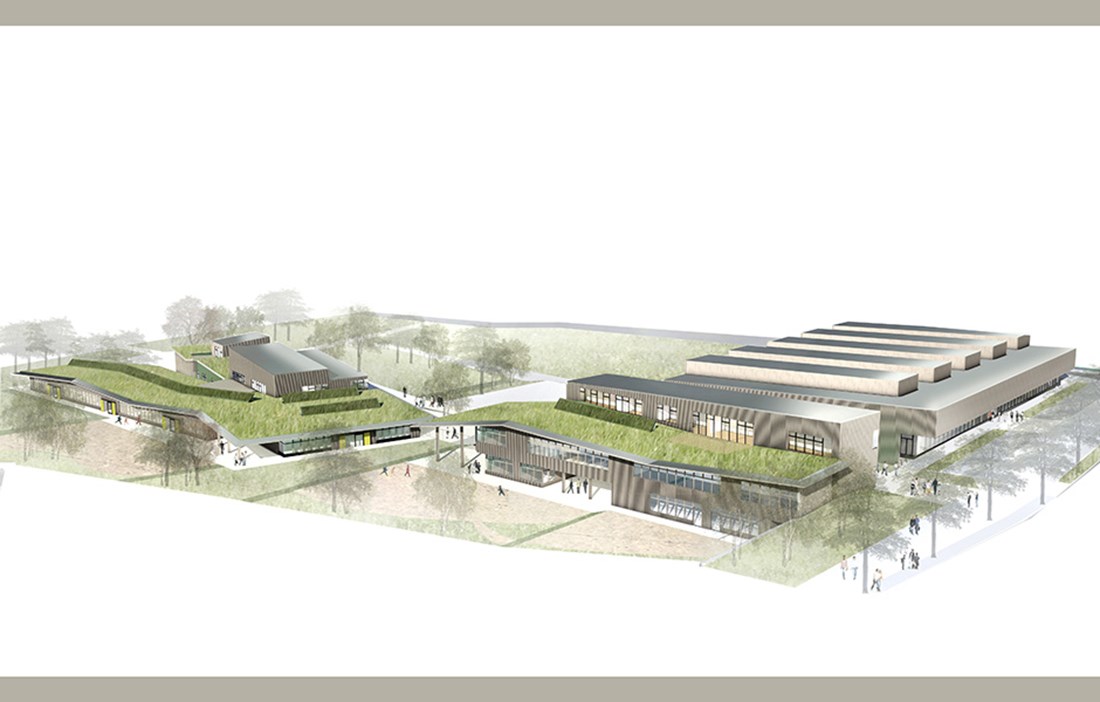

Perhaps the most striking feature of the school is the undulating roof, which slopes gently from the higher school building down to the lower one, playfully linking the two. Grass and wild flowers grow up on the roof, and there is even a small walkway. The schoolchildren also have access to two terraces on each roof, where they can have outdoor lessons. From here there are stunning views of the town and the surrounding mountains and forests.

“We wanted the school buildings to have a strong connection with nature. And the grass-lined roofs were not meant to be seen and enjoyed just by the school’s neighbours; we wanted them to be used by the pupils and teachers,” explains Lucas Jollivet of architectural firm Tectoniques.

THE COMPLEX THAT TECTONIQUES DESIGNED also includes the Hacine Cherifi sports hall. When the financial crisis hit in 2009, the sports hall project had to be shelved. However, once Europe had finally recovered, the work continued and the sports hall was soon completed. The three buildings are the result of a strong belief in wood as the construction material of the future. Tectoniques has made a name for itself in France for its strict stance on environmental and sustainability issues – and for using wood wherever possible.

“We love wood. And we want it to be seen! We don’t want to hide materials or make them look like something they’re not. Concrete is concrete, wood is wood. The materials should establish the feel and also be practical, ideally. Having a concrete substructure for the sports hall is perfect, as balls can be kicked against the walls without damaging or marking them,” says Lucas.

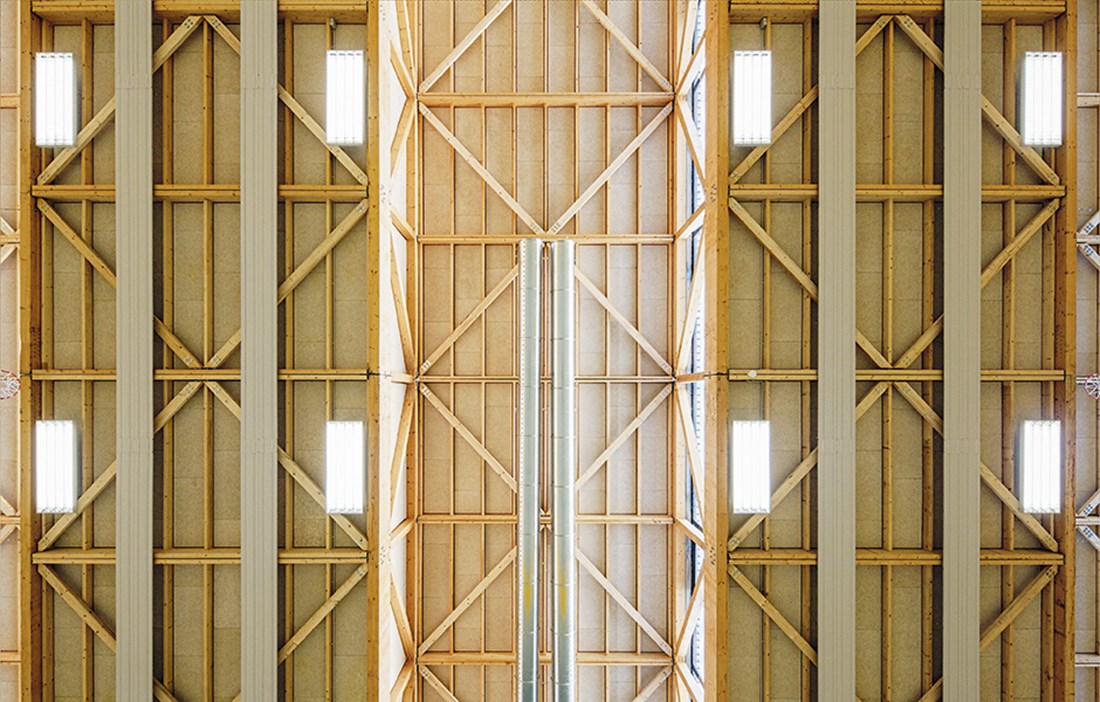

All three buildings are built around a frame of wood, and wood is used in practically everything else, including the lift shaft. The school’s structural frame comprises cross laminated timber on concrete foundations. The walls, floors and ceilings are then lined with prefabricated wood panelling. The sense of being surrounded by wood is striking, with exposed wood everywhere you go. The material can be seen and touched, and it creates a friendly feel – the classrooms and corridors exude warmth, solidity and security. The carcass of the sports hall rests on concrete foundations that hold up a large, solid wood structure. The façade is clad in locally sourced Douglas fir both internally and externally. Inside the walls there are OSB boxes filled with straw bales. This traditional way of insulating walls appealed to the architectural practice.

“When we worked it out and understood the scale of the walls, we saw an opportunity to try using straw bales. It felt really exciting! The biodegradable, natural material also felt very much in keeping with the ethos of the project,” says Lucas.

THE EXTERIORS OF the two school buildings – with their irregular façades, flowers and small outdoor spaces tucked into the quietest corner of the V-shaped buildings – playfully stand in stark contrast to the symmetrical sports hall. But although at first sight the buildings look very different, they are linked together visually. Not only are they buildings where wood has been given free rein; in terms of height they also have a kind of stepped relationship to each other. The sports hall, in the north corner of the plot, rises up highest and, via the two-storey elementary school, it all flows down to the low preschool in the south-west. The buildings sit on a slope, something that the architects exploited to keep down their height and make them fit in better with the low-rise nature of the area. The main entrance to the elementary school building is via the lower floor at the back of the hill. And the part of the lower level that is dug into the hillside – and thus lacks natural light – is where the pupils’ lockers are located. The sports hall was kept a whole six metres lower by once again using the slope. Lucas enjoyed working on every aspect of the project, but if he had to choose a favourite, it would be the sports hall.

“It may not look quite as exciting, but it typifies exactly what we want to be doing at Tectoniques. When you look at the hall, you can see with your own eyes how it’s constructed. It represents a comprehensibility, clarity and simplicity that I love,” says Lucas.

The finished result may look simple, but that doesn’t mean it was simple to construct, at least not in the case of the sports hall roof. The enormous span required 34 metre long beams that had to be transported in two sections and put together on site. An interesting feature is the way the beams are positioned to create a kind of stepped design in the roof. This made it possible to insert large horizontal windows into the roof. The windows, which face north, bring gentle, constant daylight into the hall, without the hall’s users being hit by direct sunlight. The school buildings also prioritised good light – and good acoustics. As well as attractively framing all the greenery outside, the large windows also bring daylight into the classrooms and corridors. The long eaves of the roof then prevent overly strong light from entering the building and making it too hot indoors.

EVERYTHING WENT TO PLAN with the school project in Rillieux-la-Pape. The most challenging part of the process, according to Lucas, was the fact that the planning stage took such a long time.

“It takes good preparation and dialogue with the project’s various craftsmen to keep everything on track. The electricians and plumbers need to explain early on where they need to run cables and pipes and so on, because you want to avoid changing too much once all the parts arrive on site. On the other hand, progress is quick once the building work gets started,” states Lucas.

The schools and the sports hall were completed in 2013 and 2014 respectively, and now form a natural part of everyday life for Rillieux-la-Pape and its schoolchildren. Which brings us back to the article in the Huffington Post. The text concludes by arguing that children not only become more motivated and learn maths, language or history better in an environment where grass, trees and flowers are a natural part of the school day. They also gain a deeper understanding of nature itself. When the children get to see it and learn to appreciate and love it, a generation is created that is more inclined to look after and protect nature in the future.

Text Erik Bredhe