HERRESTASKOLAN’S BRIGHT RED entrance stands out a mile among the brand new apartment blocks and the – so far – undeveloped fields in the background. The new Barkarbystaden district in Järfälla Municipality is growing at a rate of 1,000 apartments a year and on 10 January 400 pupils took possession of their new school. As the final inspection looms, Ian Craig, the municipality’s project manager for the build, looks back on an almost four-year-long process that began with an architectural competition in 2011. The winners were Liljewall Arkitekter. Their proposal was not meant to be made of wood – but Ian Craig and municipal architect Anders C Eriksson were adamant. Why? The climate!

“We said no, building this school in concrete would mean emitting around 1,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Choosing wood instead would bring us in at 900 tonnes,” says Ian Craig.

What is more, the amount of wood used to build the new school is also storing around 2,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide, which gives a net gain of more than 1,000 tonnes.

“Anders and I knocked the idea back and forth a bit. We had concerns about wood, Sweden and dampness, would it work?”

With his English roots, Ian Craig sought and found three school projects in his old homeland. His thinking was that the UK gets pretty damp, so if it can work there...

“We headed off to visit two schools in Norwich and one in London.

The result was a clear brief for the architects – change the design so it can be built in CLT (cross laminated timber).

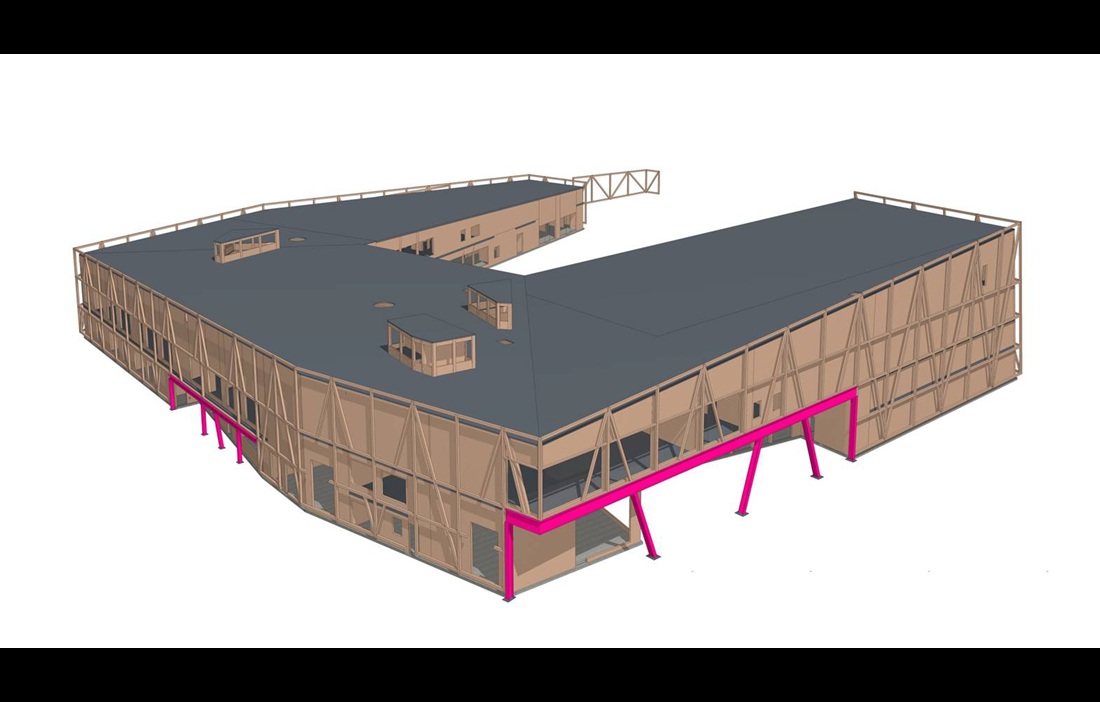

HERRESTASKOLAN IS THE FIRST SCHOOL in Sweden to be built entirely from CLT, and has a total floor space of just over 8,200 square metres. It is also Sweden’s first school to be built according to the ‘Miljöbyggnad Guld’ certification, the Gold standard of the Swedish Green Building Council. This is a requirement that Järfälla Municipality sets for all new buildings, and it ensures, for example, that the school is self-sufficient in the electricity needed to run the building, via solar panels on the roof. The certification is difficult to achieve and at the time of writing it is not clear whether it will be awarded, even though the school has been designed and built to its specifications. The greatest challenge was to adapt the building to the certification’s tough requirements for good acoustics.

The fans that drive the ventilation system generate noise and vibrations. The solution was a concrete layer on the floor. On top of the concrete rests the entire fan system, like a ship’s engine, on steel I-beams, and these in turn are fitted with sprung feet that smooth out the oscillations. This is the only place in the whole body of the building where concrete appears, apart from the raft foundation.

Plaster is only used where it is needed to conceal installations. Some of the ceilings have acoustic panels and many of the walls have narrow spruce battens mounted one centimetre apart. Behind the battens sits a sound-damping fabric. Otherwise, it is the surface of the CLT that sets the tone.

“The most difficult thing was actually to get all the subcontractors to think wood for every detail. They’ve grown up with concrete, it’s the main material for constructing large buildings in Sweden. With wood, you have to think differently!”

3,500 cubic metres of wood was used for the build. Alongside the CLT, the roof’s glulam beams deserve a separate mention. In the school’s sports hall, they have a span of over 30 metres. The largest wooden component in the roof is almost 4 metres high and weights 14 tonnes. This was one of the biggest projects that supplier Moelven had ever undertaken.

Glulam beams are also arranged in a zigzag pattern on the outside of the building. They are mainly there for aesthetic reasons, but they do have a stabilising effect – plus they serve as spacers between the CLT and the façade’s semi-transparent glass. The initial idea was that the glass would be illuminated from the inside, but in the end this proved impractical.

THE SCHOOL IS THE RESULT of a tough procurement process. All documentation from the municipality clearly stated that the design should be built in CLT.

“On that score, we drew a great deal on experience from England, where CLT is a widely used building material. It doesn’t seem to be quite as common here, at least not yet,” says Ian Craig.

In terms of fire safety, the building is fitted with sprinklers directed upwards and downwards. Regular downward-facing sprinklers provide no fire protection for the load-bearing wooden beams.

“It was a challenge for our fire safety consultants, and the textbooks weren’t much help.”

The 3 x 14 metre long structural elements were delivered with a moisture content of 12 percent, with a variation of 2 percent. But before they could be installed, they had to be dried out. The target values varied depending on where the elements were going to sit. It was quite a logistical problem on the construction site, what with the need for covering and ventilation, and may well have been the most difficult part of the job for building contractor Skanska.

“In their tenders, many consultants say they can work with wood. But they’ve rarely worked with CLT. We have the consultants we have, so we just have to hope it’ll all work out.”

THE BUILDING DOCUMENTS were drawn up by British structural engineers Smith & Wallwork. This is the same company that worked on the two schools in Norwich that Ian and his colleagues visited back at the start of the project.

“Things may have changed now, but three years ago we couldn’t find any company in Sweden that knew the ins and outs of CLT,” says Ian Craig.

“There’s a learning curve with anything new. If we’d worked in concrete, we wouldn’t have needed to pay for the consultants to gather the necessary expertise, because they have it already. We also had to do a lot of learning ourselves, in order to manage the process.”

Ian Craig’s conclusion is simple: use CLT if it works for the building. The final bill for the build is not yet in. But there is nothing to suggest any substantial deviation from the budgeted SEK 327 million, a cost that would have been around the same if the building had been constructed in concrete. This has been something of a pilot project, and there is potential to build more cheaply in the future. Certain technical solutions were more expensive, such as the acoustics, fire safety systems and ventilation. However, the municipality recouped that loss with a 14 week shorter construction time. One bonus was that, instead of the raw and damp environment that concrete creates, the construction site was warm and pleasant.

“The builders who were here didn’t want to go back to concrete, because the working environment was so nice. We even had a homeless person who would shelter here overnight!”

Text Mårten Janson