ROMSDALEN IS A stunningly beautiful valley in the west of Norway, lined by steep mountainsides and the 1,700 metre high Trolltindane mountain range, with Europe’s highest vertical drop, Trollväggen, in the foreground. At the mouth of Romsdalsfjord sits the town of Molde, the administrative capital of the Møre og Romsdal region. From here, in good weather, you can enjoy what is known as the Molde panorama, taking in 222 snowclad mountain peaks.

Romsdal Museum in Molde is an open-air heritage museum and an over 100 year-old institution. Around 40 old buildings and milieus have been gathered here for visitors to walk around and explore. This major repository of cultural history also conducts scientific research into the region’s cultural heritage. The museum’s former main building was a rather dilapidated affair. Now it has been demolished to make way for a new signature building in wood, designed by the Oslo-based and internationally renowned practice Reiulf Ramstad Architects. With its in-house design language, the practice has put its distinct touch on a number of buildings in the region, including the church in Knarvik which, with its tall, pyramid shaped spire, clearly shares a family resemblance with the new Romsdal Museum.

“Wood has a long tradition as a construction material in Norway. The fact that the site of the project is surrounded by traditional wooden buildings was another incentive to build in wood,” explains Christian Skram Fuglset of Reiulf Ramstad Architects.

The new museum building has been given a distinct atmosphere by combining innovative use of a traditional construction material with striking architecture. The building signals its function through the use of a material that prompts associations with the Romsdal region. It also manages to convey an innovative and open attitude that invites flexible use of the new museum.

“By breaking down the building’s relatively large mass and giving it a more fragmented look, the museum is also able to relate to the smaller wooden buildings in the vicinity,” says Christian Skram Fuglset.

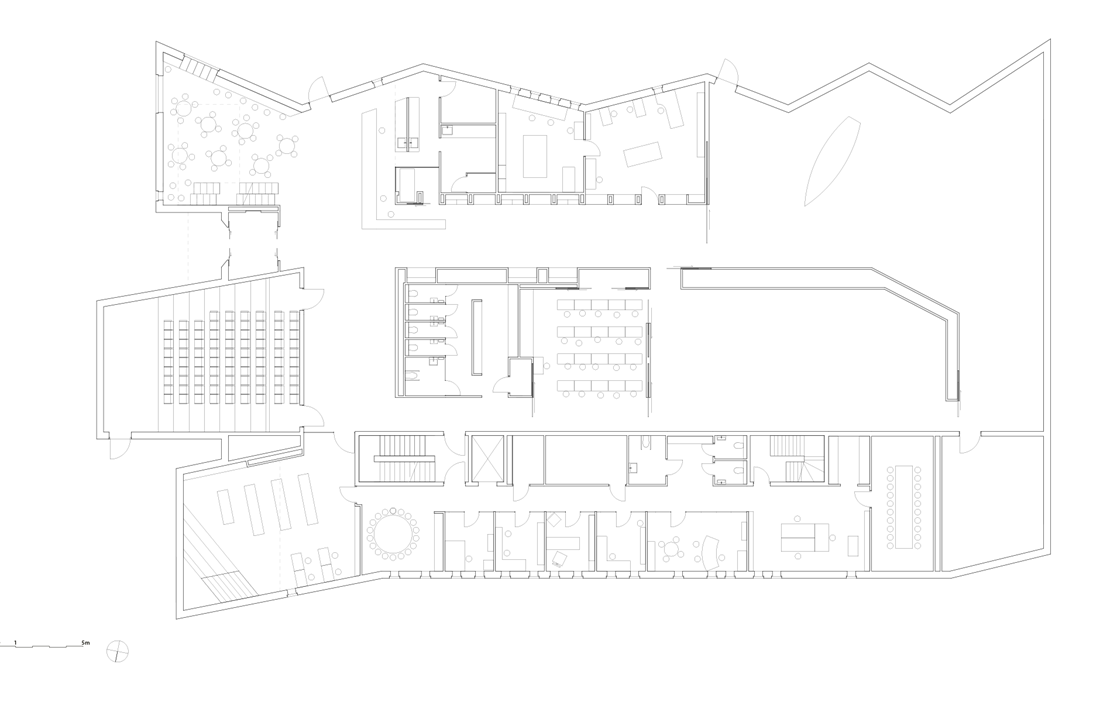

IN ADDITION TO the museum’s public functions, the 3,500 square metre main building also has to provide a haven for over 20,000 artefacts and serve as an archive for more than two million photographic negatives. The archive is located in the basement, which is made of concrete and divided into different zones within which temperature and oxygen levels can be controlled. Among the museum’s many standout features is a special heat chamber that kills pests. All the artefacts due to be shown at the museum have to pass through the chamber before they take their place in the exhibition.

Above ground, the structure comprises glulam pillars that have been combined with solid wood in the form of CLT. The solid wood panels are made up of planed spruce timber that is glued together, with every other layer rotated 90 degrees for greater dimensional stability. The result is a structural element that is rigid in multiple directions and strong in relation to its low weight. The use of CLT also offers opportunities for large spans and for efficient working methods that enable rapid assembly. Splitkon, Martinsons’ partner in the Norwegian market, supplied all the glulam and CLT used in Romsdal Museum.

JOAKIM DØRUM FROM THE COMPANY GREEN ADVISERS provides advice and support to contractors who are looking for viable solutions in wood. He was involved in the building of Romsdal Museum and is driven by a conviction that almost anything can be built in wood.

“The challenge is to keep an eye on all the details. The close collaboration with the design department at Martinsons and the skilled carpenters on site helped make construction run very smoothly. There wasn’t even a problem raising the more than 20 metre glulam pillars that form the museum’s highest feature, its spire,” he relates.

The pillars are made from spruce, which has a lower moisture uptake than pine in the sapwood. Spruce has therefore been used in the parts of the structure that were exposed to moisture during the construction process.

The museum has a mezzanine floor whose wooden structure is built around a steel skeleton. According to Joakim Dørum, this is a conservative solution that could just as easily have been rendered entirely in wood.

“The industry is awash with uncertainty and ignorance about the opportunities of wood. Unfortunately, this means that people too often fall back on more traditional solutions in steel or concrete,” he says.

The cross laminated timber is exposed in the interior and is treated with a white glaze in order to retain its pale colour. The acoustic challenges have been simply resolved using a design feature of slender battens on the ceiling and walls.

BEHIND THE APPARENTLY RANDOM placement of the façade’s many windows lies precision work by both the architects and the carpenters. The windows follow the shape of the façade and most have a fixed frame, while a few can be opened. The large exhibition spaces at the heart of the building, however, are shaped like “black boxes” and require artificial lighting.

With its peaks and unexpected angles and recesses, the roof is the building’s most eye-catching feature. Just like the entire exterior façade, it is clad in Møreroyal from the company Møretre in nearby Surnadal. The royal process involves the timber being impregnated and then boiled in modified linseed oil, known as royal oil, in a vacuum for up to eight hours. The treatment gives the wood a strongly water repellent surface, which reduces the risk of swelling and splitting. This makes both the roof and the façade very easy to maintain.

“All they need is treatment with royal oil every 10 years and to make sure that leaves and branches are regularly cleared from the roof. The great thing about wood is that you can maintain it and so extend its life. Many other materials have to be discarded once they’re done,” argues Joakim Dørum.

ROMSDAL MUSEUM’S ARCHITECTURAL FORM reflects both the region’s popular culture and the area’s characteristic landscape. It is clear that Reiulf Ramstad Architects drew inspiration not only from the bridal crown in the museum’s collection, but also Romsdalen’s high mountains and deep valleys. “The crowning glory”, as the museum is commonly known, is a fitting name for a spectacular wooden building like this.

Text Katarina Brandt