In the newly built Stanbrook Abbey, the Gothic arches are notable by their absence. It is actually only the Benedictine sisters of Our Lady of Consolation who remind you that this is actually a monastery, albeit a very modern one.

Things were very different in their old abbey in the county of Worcestershire in central England. The large Victorian building from the mid-1880s was certainly impressive, but it was built for a different time. Eventually the high heating costs and the endless repair work became too much for the nuns. In 1997 they therefore decided to realise their wish to live a modest and ecofriendly life in an abbey fit for the 21st century – a contemporary building where they would be able to focus on their main duties of prayer, study and work.

It would take them seven years to find the right site for their new abbey. After searching for land up and down the country, they finally chose Crief Farm in Yorkshire, which they acquired in 2004. They fell for the rolling hills, the light and the tranquillity, although they had no planning permission as yet. They were taking something of a calculated risk. Crief Farm is very close to the North York Moors national park, which has tough restrictions on what can and can’t be built.

The dedicated nuns began looking for an architectural firm that could realise their plan for a new abbey designed for a sustainable way of life, through ecofriendly material choices and through innovative technical solutions aimed at minimising the building’s environmental impact. Today the abbey is heated by a woodchip boiler, it has a sedum roof and solar panels, and it harvests rainwater. Wastewater is filtered through a reed bed, where the water slowly soaks down into the ground as a natural biological purification process takes place.

Having interviewed several architects, the nuns ultimately chose Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios (FCBS), which has an explicit eco-profile and a host of prestigious awards to its name.

“I think they chose us because we showed an understanding of their way of life and were open to working with them on their terms,” says Peter Clegg, the chief architect over the course of the project.

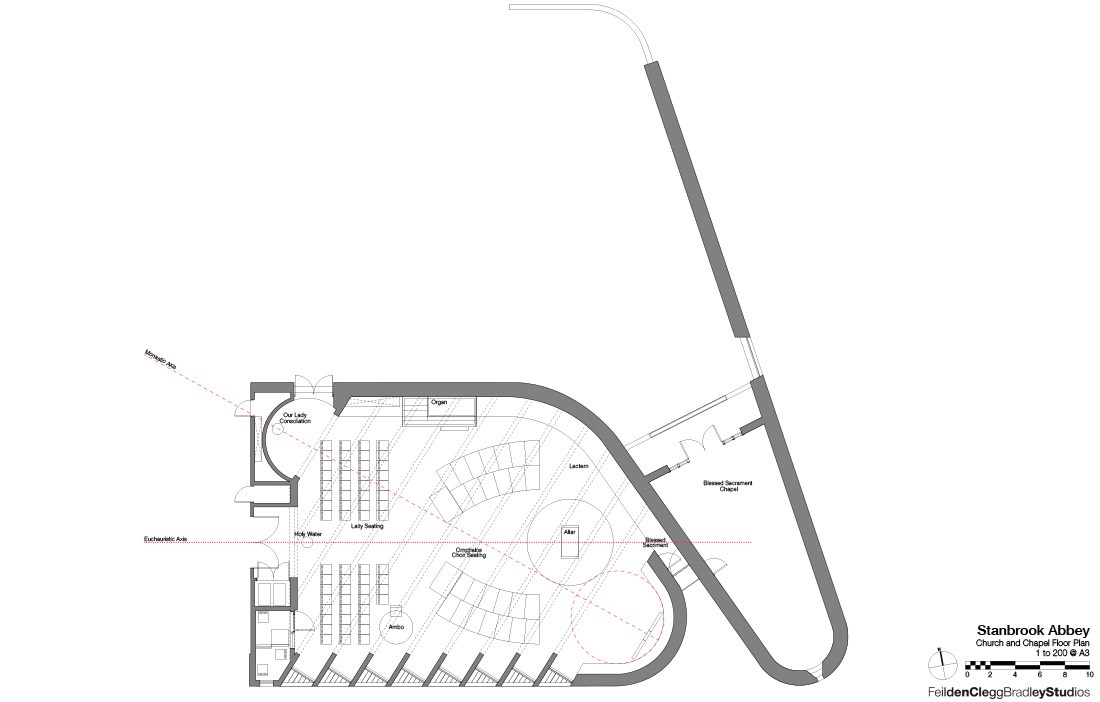

In order to fund the new abbey, the build was split into two phases. The first phase was completed in 2009 and comprised 26 cells for the nuns, a kitchen and dining room – known as a refectory – and a number of workrooms. The nuns moved into this building that same year, even though the key religious spaces remained absent. Following the sale of the abbey in Worcestershire, work was able to begin on phase two. It was completed in 2015 and is architecturally the most important part of the new abbey. It houses the church, a chapel, an assembly room and a number of guest rooms.

“Perhaps the biggest challenge we faced was getting the necessary planning permission since the planning officers don’t usually allow any form of development within the North York Moors national park. However, they chose to make an exception for Stanbrook Abbey, as they saw the value of reviving Yorkshire’s long but dormant monastic tradition. In our case, they invoked the discretionary clause for ‘an extraordinary building for extraordinary people’. The nuns are extraordinary in many ways, and we also hope that the abbey will be seen as extraordinary,” says Peter Clegg, who also mentions the minimal budget as another challenge.

Stanbrook Abbey has both public and private spaces, with the first phase arranged around a large inner courtyard, a quadrangle, which is traditionally a key component of a monastery’s layout. While the first phase is austerely designed in an orthoganol check pattern, phase two has a very different look. Here FCBS has gone all out to realise the nuns’ wish for soft, organic lines that hint at how this is a building in which only women work and live.

Although wood doesn’t play the lead role in Stanbrook Abbey, it is a prominent material that is used generously in the monastery as a whole and in the church in particular. It has qualified the abbey as one of the finalists in British architecture’s Wood Awards 2016.

The church’s roof structure is supported by substantial white-glazed glulam beams that rest on angled glulam pillars. These wooden components combine with tall sections of glazing to form the southern façade of the church. The ceiling is clad in wooden tongue and groove made from Douglas fir. The choir stalls and organ are made from English sycamore, which is a light, knot-free wood closely related to maple. The rear wall of the church is also clad in sycamore. The panelling is not just aesthetically attractive, but also serves an acoustic function as a sound reflector.

“Our intention was to make the church, where the nuns spend much of their life, a place that changes through the course of the day, depending on the weather and the season,” says Peter Clegg. “The mix of glulam and glass creates an exciting play of light and offers both views of and contact with the landscape outside. The large windows are an example of the Vatican becoming more liberal in its view of what a monastery building should look like. Allowing the nuns to look out onto the beautiful countryside helps rather than hinders them in their calling.”

The façade is finished in a combination of sandstone and sawn PEFC-certified oak cladding. The oak was grown locally. When freshly sawn, it varies in colour – from pink to a hue of golden honey. As the surface dries, it becomes a yellowy gold and then as it weathers over time it turns an attractive silver-grey. The thinly sawn sandstone is made from recycled waste pieces.

Work on Stanbrook Abbey involved a close and highly creative partnership between architect and structural engineer. A number of components were tailormade, for example, to have multiple functions in the building. The curved reinforced concrete walls, which lead visitors into the church and then rise ever higher to culminate at the altar, support the wooden roof structure, while also compensating for the variations in the ground level and providing overall stability.

“We chose wood for the roof structure and parts of the façade because the material harmonises with nature and fits in well with the nuns’ preference for sustainable materials. Wood is also light and easy to handle and work with manually on site. This meant we could reduce the number of heavy loads that we brought down the narrow country roads,” relates Peter Clegg.

The use of wood has also helped the abbey to sit comfortably in its surroundings. It has a dignified but modest look, and it merges into the landscape unobtrusively. However, the abbey is not yet fully complete. A third and final phase that will house the library and its archives still remains to be built. The start date for this phase depends on the success of fundraising and donations.