Appropriately, Michael Green and his company MGA – Michael Green Architecture – have an office where wood is a dominant presence at every turn.

The industrial building from the early 20th century in Vancouver’s Gastown in Canada is bursting with character, with large windows overlooking the street, high ceilings and substantial columns of Douglas fir that were part of the building’s load-bearing structure right from the start.

Michael Green comes in and sings a well-rehearsed – but the same time, fascinating – love song to wood as the construction material of the future.

As a resolute advocate for tall buildings in wood, his stock seriously rose following his talk at TED2013, a recurring conference on new ideas within technology and design. His 12-minute talk on how the world can successfully resolve the equation of building more and more housing, while at the same time stopping the threat to the climate, has been downloaded more than 1.2 million times. His message is clear: Save the world. Forget steel and concrete. Build in wood.

As a newly qualified architect in the US, he soon realised, however, that wood was a relatively untested construction material for commercial buildings in American city centres. And so he relocated back to his native Canada, more precisely to Vancouver, where there was a very different interest in new construction materials and more unconventional ways of thinking.

Over the years, he has produced many examples of large buildings that exploit the environmental, technological and economic possibilities of wood. With every project, he and his team seek to take another step forward and show something new that could prompt the construction industry to turn a new leaf.

“Ten years ago, people said I was crazy to be talking about building high-rises in wood, but now we have the technology to build 30 storeys or more,” declares Michael Green.

The technology he is talking about includes prefabricated structural components based on cross laminated timber (CLT or crosslam). This is an engineered wood product that first appeared in Austria in the 1990s, made from planed spruce that is glued together in layers, with every other layer rotated 90 degrees to increase strength and dimensional stability.

“The technique is also smart for the climate, since it allows the use of poor quality, or even sick, trees that would otherwise have been left in the forest. There they would likely have fallen over and released large quantities of carbon dioxide,” he says.

Michael’s first breakthrough came with the expansion of North Vancouver City Hall. It is not a particularly tall building, but it uses laminated strand lumber (LSL, beams made in a similar way to OSB) in the frame and for the roof and walls, with highly successful and much praised results.

Since then, the construction projects have come flooding in. Michael Green combines these with lecturing all over the world – like in November 2016 when he gave a lecture in Stockholm at the ceremony for the Marcus Wallenberg Prize, which promotes innovative research in the forest industry. He stated that a skyscraper built around a wooden frame is entirely possible, and showed how the Empire State Building could have been constructed.

He has also written a report titled The Case for Tall Wood Buildings, in which he expands on his ideas about safe, economical and environmentally sustainable alternatives to steel and concrete. “The first significant challenge to steel and concrete in more than a century, with the potential to revolutionise the building industry,” is how he describes the 240-page report, which is packed with diagrams, details, examples and technical solutions – all free to be copied by anyone who wants to.

“95 percent of my work is about getting people to understand what wood can do,” explains Michael Green.

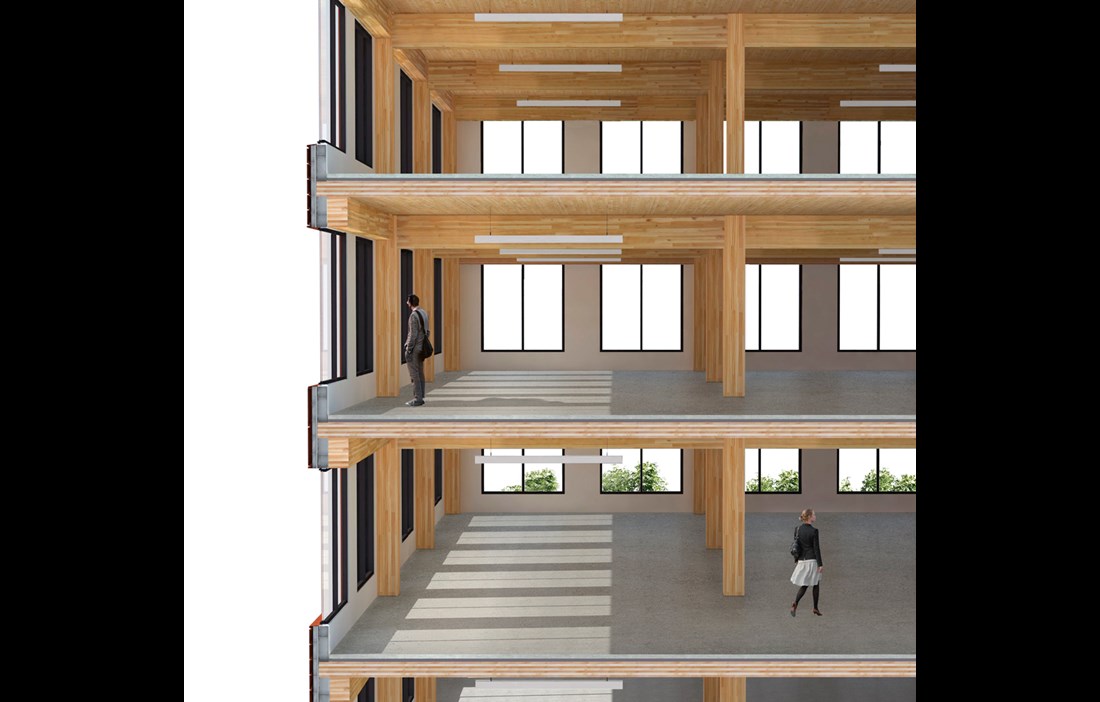

The report led to a commission to design an attractive building entirely in wood, the Wood Innovation and Design Centre, for research and innovation in wood-based design at the University of Northern British Columbia in Prince George. The six storeys of the rectangular building are at the same time intended as a showcase for new construction methods based on engineered woods such as glulam, LVL, crosslam and so on, with various solutions for joining them together.

“This is probably the most technically advanced wooden box in the whole of North America,” muses Michael Green.

2017 will see the launch of Timber online education, TOE (timbereducation.org), aimed at taking a holistic approach to all aspects of wood construction and properly reaching out to actors around the world who work in the construction industry – architects, engineers, technicians, builders, clients, etc. This is a free, web-based training programme initiated by Michael Green and his colleague Eric Karsh. The idea is to offer courses where experts from all over the world, in several different languages, share current research and technical advances in wood construction.

“It’ll be easier to make things happen if everyone doesn’t first need to go through the same process that we have,” says Michael Green.

“We hope that having a shared expert forum that delves deep into relevant issues surrounding tall buildings in wood will yield faster results.”

Michael Green’s latest design project, which opened in November last year, is a 7-storey office block with 20,000 square metres of floorspace in Minneapolis, USA, called T3. He admits that this is a simple-looking building, but at the same time he claims it is the tallest modern wooden building ever to be built in the USA.

“The US construction industry is more conservative than in Canada and it’s important to have examples of modern wood construction that can break new ground.”

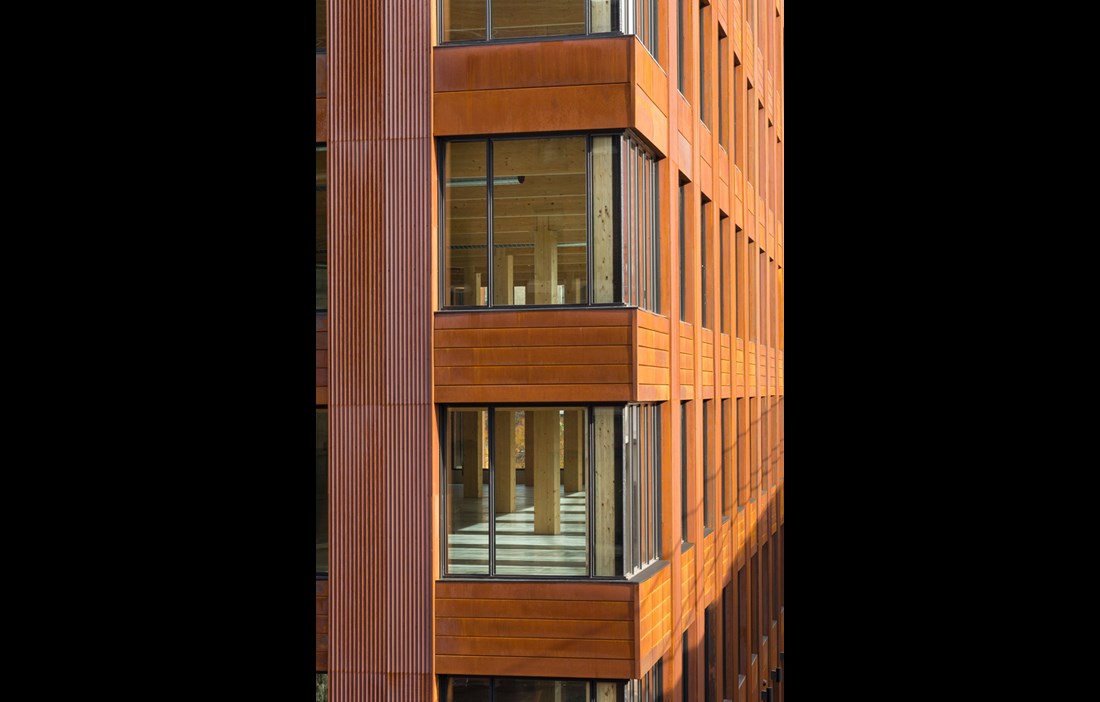

T3 stands in Minneapolis’ historic industrial district, The North Loop. At the turn of the last century the railways had their workshops and engine sheds here, and there were also factories and large warehouses, built from wood, iron and brick.

Now the area has undergone a radical facelift, with expensive apartments, popular restaurants, creative companies and trendy shops. The majority of the residents are aged between 25 and 34, and Forbes Magazine has named it “The hippest neighborhood”. The brief given to MGA was to create a wooden building that was modern in every respect, referenced the area’s history and merged seamlessly into its robust surroundings, a building that would attract companies looking for a place that embodied local creativity.

Michael Green sums it up as “a quiet building that isn’t trying to make a big statement externally or be a manifesto for the architect, and the interior is beautiful and inviting, with large expanses of exposed wood.”

In contrast to many other modern wooden buildings which make wide use of crosslam, the material choice for T3 has been nail laminated timber (NLT, nail-lam) for the 20 centimetre thick floor joists. This has entailed dusting off a low-tech, well-proven and good value alternative to modern engineered woods. NLT has been used for over a century and basically comprises planed 2x8 inch planks nailed together on edge to form a rough and ready mass timber product. The majority of the wood used for T3 is taken from pines hit by the mountain pine beetle.

Using glulam posts and beams, the load-bearing structure for the whole of T3 was able to be erected in less than 10 weeks – nine days per storey – which is significantly shorter than for a conventional building in steel or concrete.

Having a ground floor with a concrete slab cast over an acoustic mat and taped OSB panels has made the client more comfortable with the building’s wooden structural frame. A façade of weathering steel not only keeps the elements at bay but enables the exterior of T3 to sit comfortably in its historic industrial setting.

“Maybe what we have here is an American prototype for future commercial buildings in wood,” says Michael Green.

Read more on Michael Green Architecture

Text Mats Wigardt