The area of Barangaroo is Sydney’s largest urban renewal project since the Olympics in 2000. It is one of the most extensive seafront transformations being undertaken by any city in the world. And Australia’s first really big office block built entirely in wood has just been completed here. The International House building is six stories high, with almost 8,000 square metres of floorspace, and it is made from over 950 cubic metres of glulam from Hess Timber in Germany and more than 2,000 cubic metres of CLT that was produced at Stora Enso’s factory in Austria and then shipped in containers to the construction site.

The latest addition to the Bangaroo cityscape has its roots in the past but with the addition of the very latest in design and technology. The aim of this is to ensure a long and sustainable life and to enable easy repairs, additions and ultimately disassembly. The choice of construction material is in a way linked to Sydney itself and this part of the city’s close ties to the ocean. The harbour served as a transshipment port and wood was the material used to build warehouses, jetties and bridges.

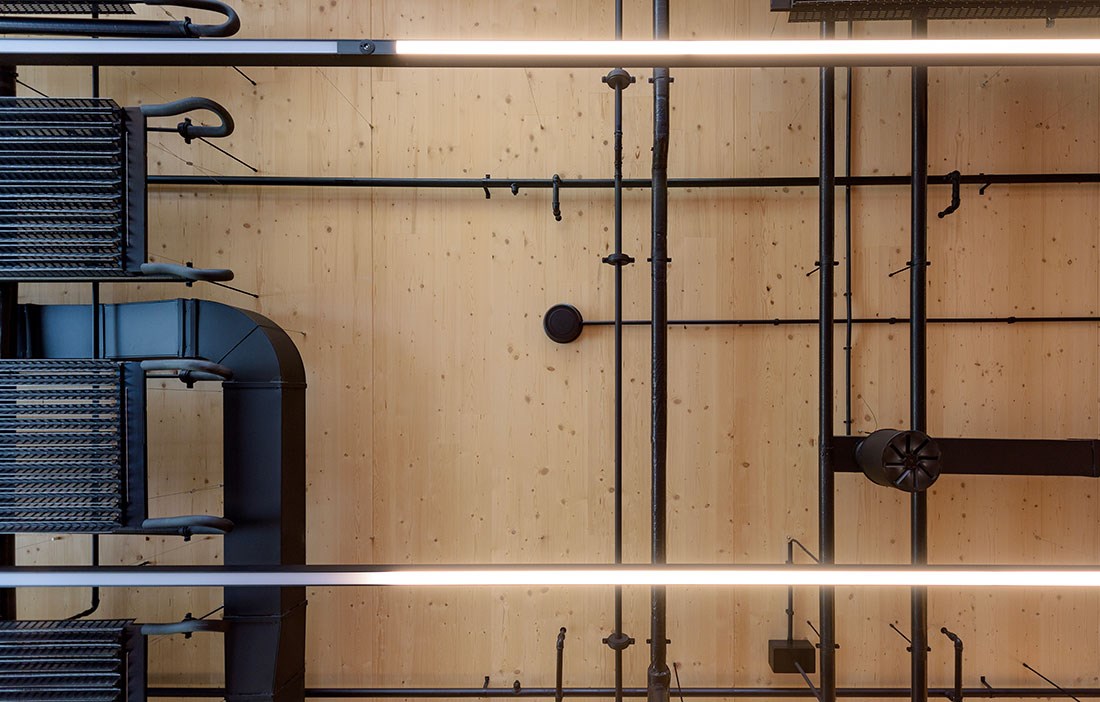

Light floods in through the fully glazed façade, accentuating the bold look of the exposed wooden structure. The whole property was built using glulam and CLT, from the first floor upwards, including the lift shaft and stairwell. Only the ground floor is made from concrete due to fire safety regulations. Wood is also used in the double-height colonnade on the street, which is made from recycled eucalyptus recovered from 100-year old railway bridges in the states of Queensland and New South Wales.

“We liked the idea of bringing old wood back to life and giving it a place in a new age and a new context,” says Alec Tzannes of the Tzannes architectural practice in Sydney who, together with his colleague Jonathan Evans, was commissioned to design International House.

“We chose wood primarily because it’s a renewable resource, but also because of its tactile properties. Wood is soft and warm to the touch, it smells wonderful and it’s entirely free from toxins. It gets more beautiful with age and people who spend time around it have a better sense of wellbeing.”

The greatest challenge in the project was achieving the ceiling height that is required on every floor of commercial buildings without exceeding the building’s overall height. This meant that channels would have to be cut out of the glulam beams to accommodate certain technical installations, but this ran counter to building regulations. The solution was a new type of reinforced glulam beam: a kind of hybrid where traditional glulam made from spruce boards is bonded together with two sheets of beech LVL for full strength.

“We consciously took away all the wall and ceiling cladding internally to strip back material use in the project and expose the wood as much as possible,” explains Jonathan Evans.

“The glulam beams provide integral fire safety and can resist a fire for 90 minutes without losing their load-bearing strength. The surface treatment is just a thin, matt varnish that was applied in the factory – mostly to provide a little extra protection during transport and assembly, but also to retain the blond wood feel.”

Building International House has attracted a great deal of attention locally and every time one of the many gigantic glulam beams has been floating in the air, traffic and pedestrians have stopped for a moment to watch them slide into their proper place in the building.

“The extra time and care that we put into the digital design process really paid off on the construction site. Despite the minimal tolerances, all the structural elements fitted perfectly, which meant there was no need to interrupt the construction process,” continues Jonathan Evans.

There has been strong interest in renting the offices in International House and consultancy firm Accenture will shortly be moving into one of the floors.

“The response has been overwhelming, from colleagues in the industry, property developers and people who visit the building. Everyone comments on what a good effect the presence of wood has on them,” says Alec Tzannes.

Japanese architect Aki Hamada also took on the challenge of using wood flexibly when creating Substrate Factory Ayase. The building is situated in the city of Ayase in the Japanese province of Kanagawa. Here, factory buildings and apartment blocks stand side by side in some form of co-existence. Aki Hamadan chose to use wood as a way to better convey the relationship between factory and housing.

Substrate Factory Ayase is a newly built extension to an existing circuit board factory right next to the US Marine Corps’ Atsugi airbase. Initially, the first floor was meant to house workshops, but the plans changed and now it serves as a multifunctional meeting place for the local community.

“Together with our client, we began to think about how we could make a factory building fit in and be part of everyday life in a vibrant residential area,” relates Aki Hamada.

The result was an open wooden structure that helps to soften the relationship between the different types of building. It lends a warmth and natural counterpoint to the surrounding industrial buildings. It was also relatively simple to shape the material to follow the roof’s complex geometry.

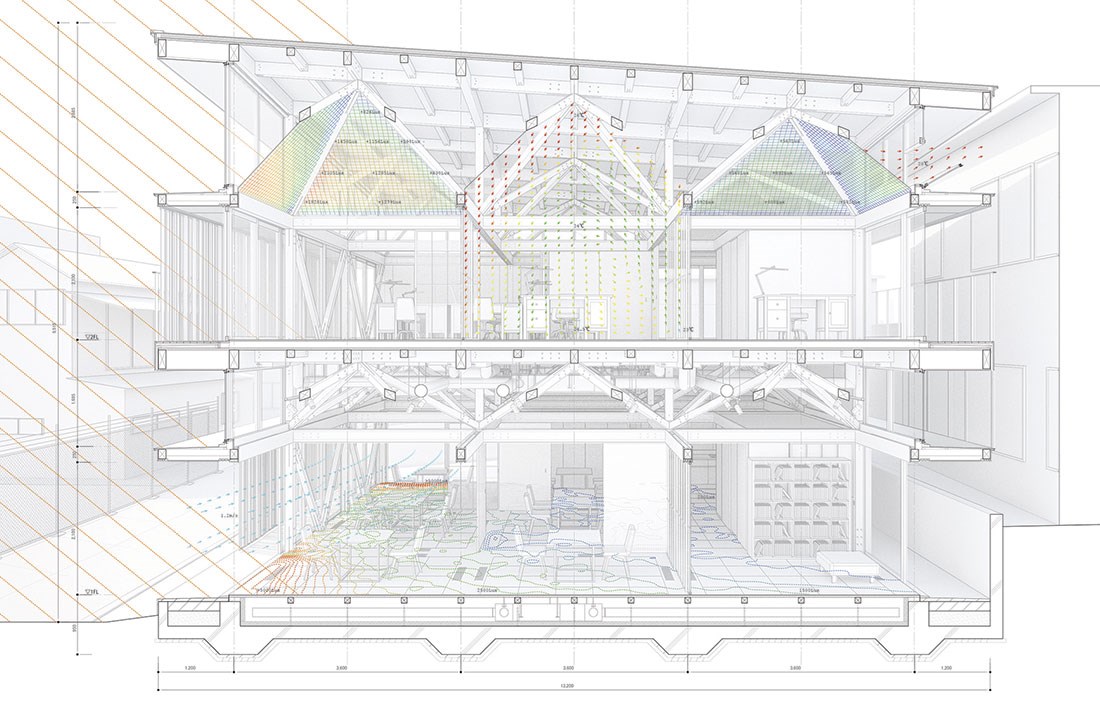

The next challenge was the purely practical realisation of the wooden structure and then creating the interior conditions for optimum use of the space. Flexibility and versatility were a key focus, as it wasn’t entirely clear how the building was going to be used. It therefore had to be easily changed to meet both contemporary and future needs.

Internally, the solution was to use wooden partitions that could easily be moved around the space to create a wide range of different rooms. The walls slide on milled tracks in the floor and in the glulam beams that form part of the ceiling. The ceiling structure is fully exposed on both floors and held up by a thoughtful pattern of diagonal and horizontal glulam beams. On the upper floor a transparent fabric has been stretched between some of the beams to filter strong sunlight.

The advanced joinery technology has echoes of traditional Japanese wooden architecture. In practice, the structure can be disassembled and reassembled without any great adverse effect on either the materials or the surroundings.

The exterior walls also offer considerable flexibility and create a diffuse relationship between closed and open, outside and in. They comprise two layers, the outer of which is semi-transparent laser-cut steel and the inner of which is transparent, sliding glass walls. To control the level of privacy from the street and adapt the light coming into the east side of the building, the outer walls can be adjusted as the sun moves through the day. At night, the building is illuminated from inside, which further enhances the wooden structure.

“We didn’t make any physical models when we were designing the wooden structure. Instead, we applied a method of parametric modelling known as an adaptive model. This gave us an opportunity to handle all the information freely and study many different behaviours,” explains Aki Hamada.

He feels one of the advantages of parametric modelling is that you can begin with the whole and then refine it by adding and relocating different details. You can also turn it all around and begin by defining the details and then gradually working outwards towards the whole.

“The latter approach is often used when, as in our case, you want to create new details that will fit into a specific project. For us, it was important to have an open input format that uses 3D software and programming, instead of using an application with a predefined input format for our design process.”

In Aki Hamada’s opinion, one of the benefits of the technology is that it allows even small design agencies to make objective comparisons and studies of a large number of variations, without losing the strengths of being a small agency.

“We hope the building will be fully embraced by the local population. We want it to work as a flexible meeting place that can easily change character and functionality from day to day, depending on what activities are on the agenda,” concludes Aki Hamada.

Text Katarina Brandt