Dreams and anticipation, queues and delays. Most of us are conflicted about airports. Andy Warhol was one of their greatest advocates, as they provided his favourite foods, favourite toilets and favourite peppermint pastilles. British design critic Reyner Banham, on the other hand, has expressed his disdain and called them a “demented amoeba”. Christian Henriksen, partner and design manager at Norway’s Nordic Office of Architecture, has a more nuanced relationship with the buildings.

“Working with airports is fascinating. Many of them look the same the world over, so there are great opportunities to do something new, special and different. However, everyone knows that aircraft are responsible for considerable air pollution. As an architect, I therefore want to do everything I can to reduce the carbon footprint of the airport itself.”

Christian Henriksen has been involved in designing airports all over the globe, including in Turkey, India, France, Iceland, Uganda and Sweden. Nordic also designed Oslo Airport, which was completed in 1997. Then last spring – 20 years later – an airport extension, also by Nordic, was opened. The airport was originally built to handle 17 million passengers a year, but now it can handle an impressive 32 million.

“It was a huge job that took a great deal of planning. Everything you do in the construction phase has to be reported well in advance so that air traffic and safety are not affected in any way. What’s more, the safety measures for airports have changed a lot in recent years, which meant we were forced to keep the design of certain parts open and see how things developed,” says Christian Henriksen.

Keeping the airport working seamlessly during the extension work was not easy – but it was essential. As well as being at the heart of Norway’s expansive air traffic system, Oslo Airport is also what finances the operation of many of the 60 or so smaller airports across this topographically challenging country. But the project went well, with all the planning paying off. During the construction phase, Oslo Airport was named the most punctual airport in Europe – twice.

One of the watchwords for the project was simplicity. Travellers want to feel relaxed, safe and well looked after. The old buildings set the tone for the extension, as it was important for them not to feel like two separate units. The flow through the airport was always a priority. Thanks to its logical layout, with several recurring elements, the building is more or less self-explanatory. As such, it requires less signage and fewer PA announcements. The pervading sense of calm and the striking architecture are intended to make arriving passengers feel welcome to Norway and Scandinavia.

“We focused a great deal on the dearly held values of Scandinavia and let them manifest themselves in both the forms and materials. The new terminal building thus has a sense of openness and security. Transparency and clarity. And closeness to nature,” says Christian Henriksen.

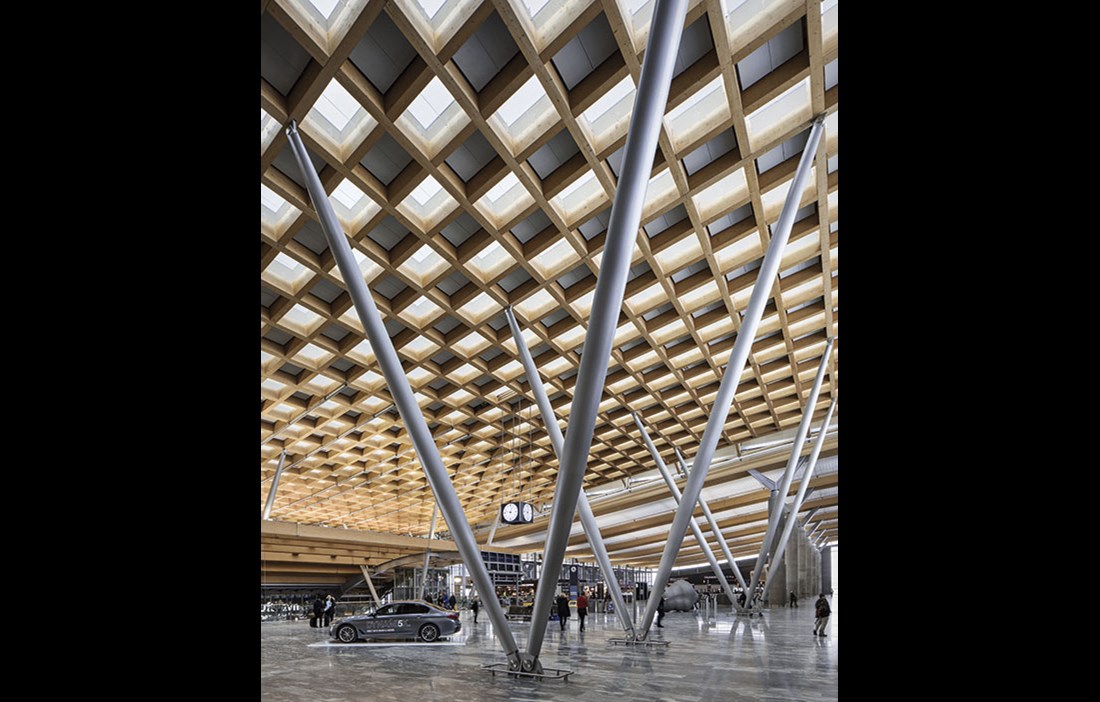

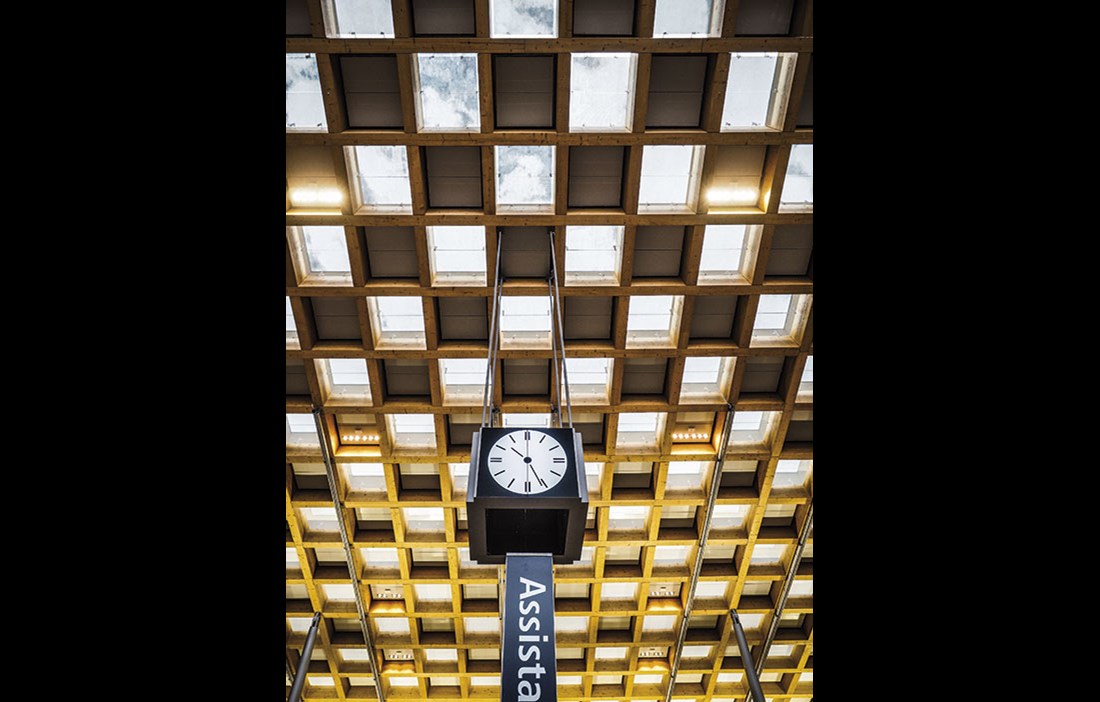

Large panoramic windows enable passengers to enjoy the landscape around the airport. Many places in the terminal have walls of plants and small water features that recall the natural beauty of Norway. All the materials were meant to be used in as natural a form as possible. If it’s glass, it should look like glass. Stone should be stone. And wood, which plays a starring role at Oslo Airport, should take pride of place. The architects used wood in two main ways: structurally and for atmosphere.

“We wanted to use wood in the structure and keep it exposed. Wood defines us here in Scandinavia and it would therefore also define Oslo Airport. We’ve used wood in various different parts of the airport where we wanted to create a particular atmosphere – in the areas where the passengers spend a lot of time or where they want a certain amount of calm,” states Christian Henriksen.

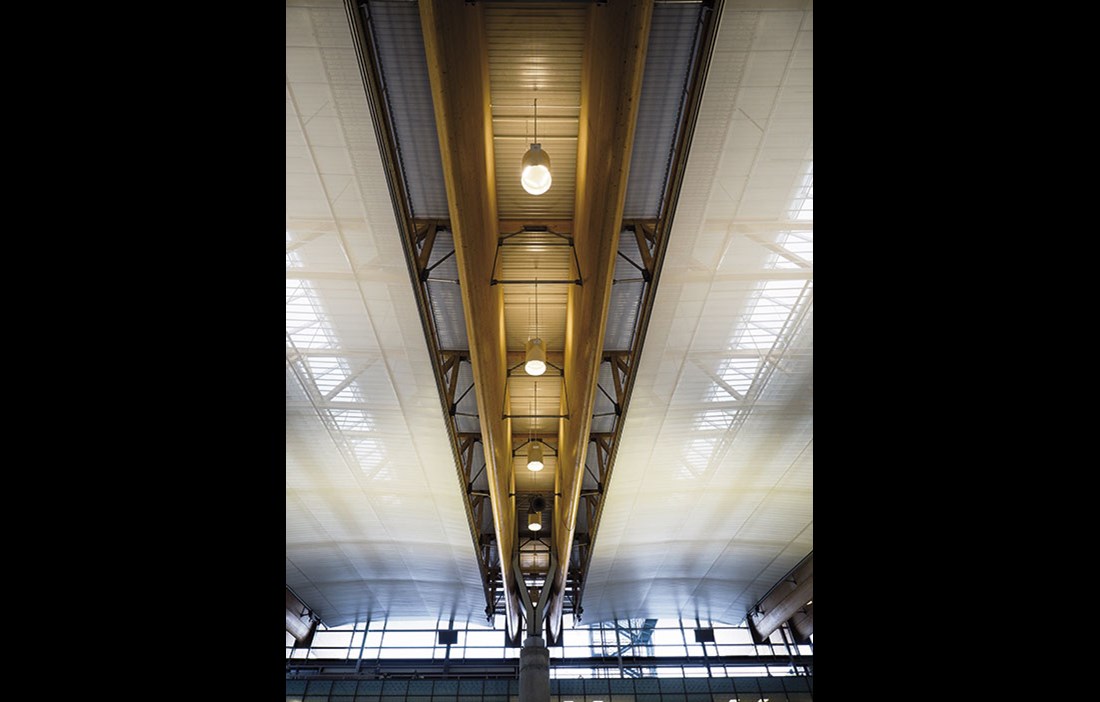

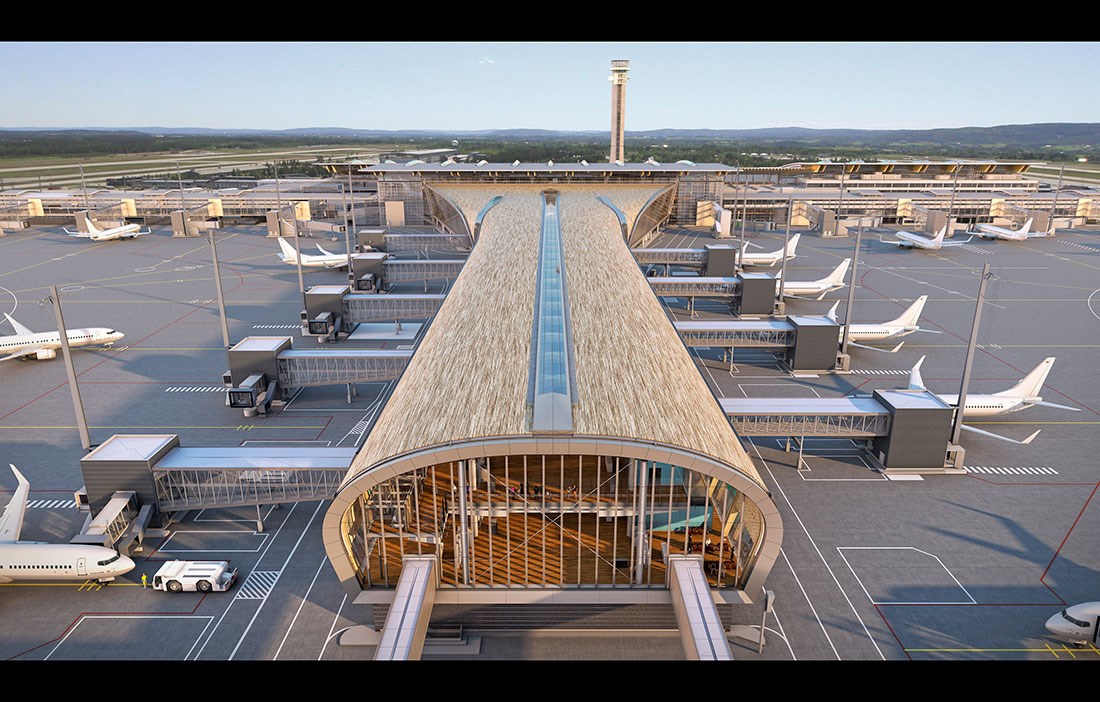

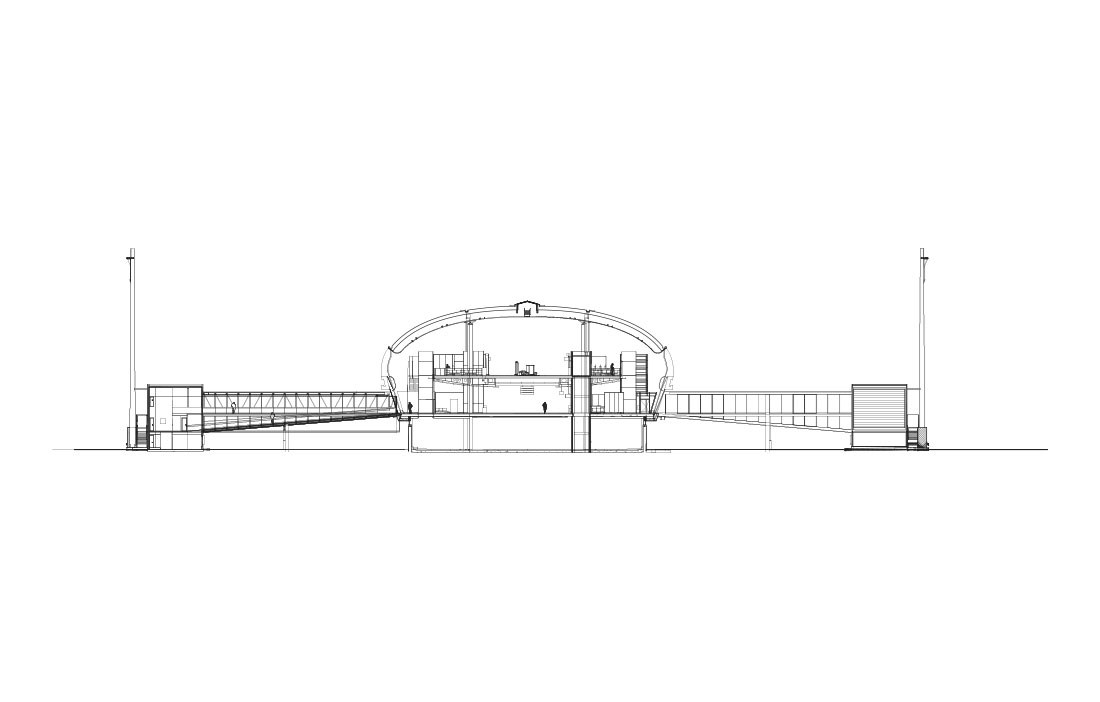

Nordic expanded the existing terminal and modernised the train station that serves it. But the biggest change was the construction of a 300-metre long pier that extends out onto the tarmac airside. The slightly futuristic, rounded pier is held up by a series of glulam arches that use wood from Scandinavian forests.

Where the pier meets the original terminal, the rounded form spreads out like butterfly wings to bring the two buildings together in a natural way. This area houses the duty-free stores and is where the domestic and international travellers part ways – domestic upstairs, international downstairs.

The façade is mostly glass to let in as much daylight as possible, while the roof is finished with oak cladding. Around 20 centimetres beneath this is an additional protective roof that deals with water run-off and keeps the external wooden façade well ventilated. A transparent and UV-resistant paint is the only treatment used to protect the oak cladding. The wooden façade gives the pier an attractive aesthetic, but its most important function relates to airport safety.

“A pier like this that extends out towards the runways can cause problems for the air traffic control tower. The signals they send to the aircraft on the ground are highly sensitive to distortion and can easily be reflected, for example by metal, which creates false signals that can lead the plane astray. But with a wooden façade, the signals die when they hit the pier,” says Christian Henriksen.

Such wide use of wood was also a way to meet the strict environmental requirements set by the clients. All the materials were carefully chosen based on their carbon footprint. The concrete in the design was mixed with volcanic ash and more than half of the steel is recycled metal. The peer has its rounded shape to minimise its contact surface and so save energy. During the winter, the snow cleared from the runways is stored in a space below the terminal so that it can then be used to cool the terminal during the summer months. This reduces the terminal’s energy consumption by 2 GWh per year. As a result, Oslo Airport is ranked as “excellent” under the BREEAM environmental certification scheme and the extension is considered one of the world’s greenest terminals: the airport has cut its carbon emissions by 35 percent and halved its energy consumption compared with before the extension – while at the same time doubling the airport’s capacity.

Christian Henriksen looks forward to using wood to a greater extent in even more Scandinavian projects. But he does see a cloud on the horizon.

“We have the knowledge and the material, and there are highly sophisticated techniques for using wood in large structures. But certain conditions and regulations are impeding progress, which means we don’t always manage to unlock the huge potential. That’s something we really have to change,” he says.

Text Erik Bredhe