We follow the outer ring road around the city, past trees, open fields and the usual temples to shopping that occupy the plains of Östgötaland to reach Linköping’s newest urban development, Vallastaden. Tens of thousands of new homes are set to be built here, with the aim of creating a link between the city and the university.

The ambition is to create a small-scale and sustainable neighbourhood where a large number of smaller players are given the opportunity to innovate and deliver diversity. A thousand apartments have already been completed and they took centre stage in this year’s housing expo, which has now ended.

“With smaller plots and quality criteria rather than price dictating the land allocation, we have six times more developers on this project than we would usually have,” explains Rickard Stark of Okidoki Arkitekter, which is responsible for the master plan for the area.

With a clear focus on ecology and community, the result is a varied and densely built development with an innovative range of heights, façade materials and roof angles, terraces and access balconies, but still with space for streams, allotments, parkland and forest.

Instead of setting the maximum height of a building, up to four floors have been permitted instead, which means that wooden buildings are not disadvantaged. Wooden buildings tend to have thick floor structures, which can reduce the number of possible storeys and cause viability problems for the developer.

“We’ve prioritised wood in the land allocation, which now means that ten of the forty multi-occupancy blocks in Vallastaden have a structural frame of wood,” says Rickard Stark.

One of these is 3k, or Delfinernas Hus, a cuboid little building in CLT by Arkitektstudio Witte, which is also acting as the developer.

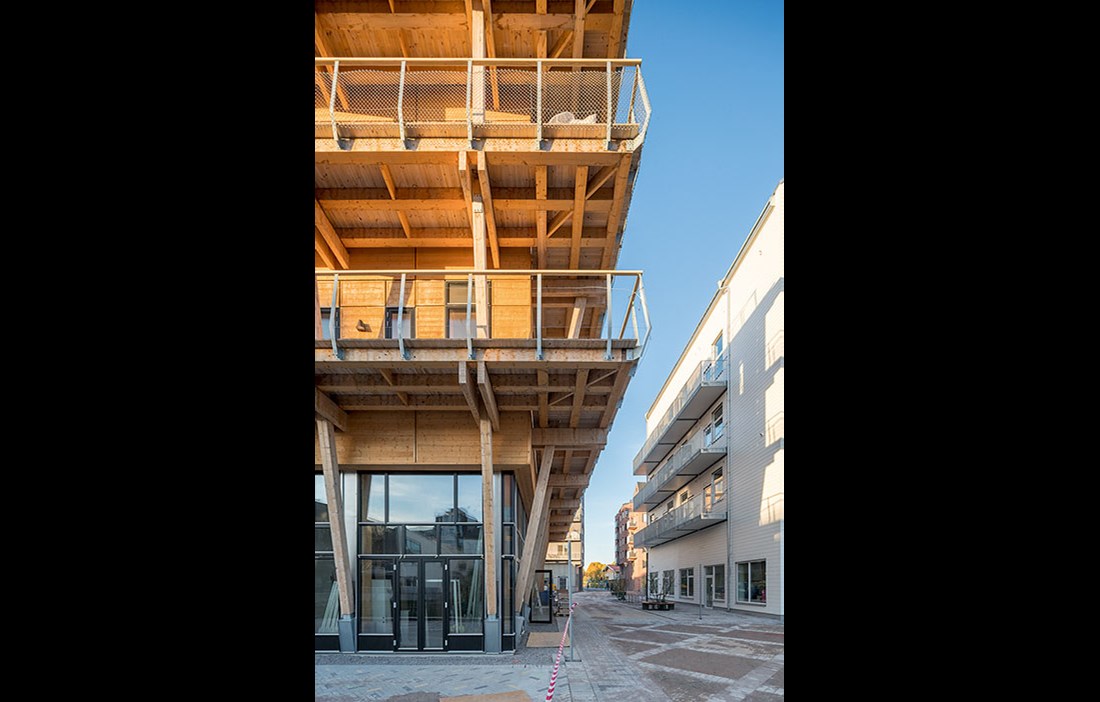

The block is being built with four floors, creating space for 15 compact owner-occupied apartments, most of which have loft beds and high ceilings. Playing with the formability of CLT, the floors are clearly demarcated as they extend out over the street, determining the dynamic of the building and drawing inspiration from Sweden’s old log cabins.

“The design hasn’t been used anywhere else. Vallastaden hasn’t had the usual standard dimensions to take into account. It’s more a case of having a volume to fill,” states architect Ludvig Witte.

CLT components have been used for the frame, the floor structure and the balcony slabs. The roof is also made from CLT, with an outer cladding of living plants in what is known as a sedum roof. The façade is finished in glulam cladding, with a great deal of work going into creating a modern design with ornamented surfaces that clearly reference their historical inspiration.

“We’ve long wanted to work with CLT and premiere it at the housing expo. Martinsons are supplying the material and they’re also involved in planning the building,” says Ludvig Witte.

Arkitektstudio Witte has designed a total of five residential blocks in Vallastaden, all with a structural frame of either CLT or glulam.

“The housing expo is a great place to learn lessons that you can then apply to other projects,” adds Ludvig.

The theory that future apartment blocks will be made from wood is one that the architects at Spridd have also nurtured since they began in 2005. Having recently entered into a fruitful partnership with wood supplier Moelven, they have now completed Träloftet in Vallastaden.

This is a rectangular apartment block on four floors that contains 20 small one- and two-bed apartments with high ceilings. The design may not have spectacular features, but architect Ola Broms Wessel describes it as simple and direct in its tone.

“We’ve focused most on interior quality and used the conditions in the plan to maximise the living space in the property. The challenge is not to plaster over the wood, but to leave it visible,” he explains.

Träloftet has been built using Moelven Töreboda’s post-and-beam frame system Trä8, which is capable of spanning up to eight metres. According to Moelven, the system shows that it is perfectly possible to create stable, flexible and eco-friendly buildings in wood. In Träloftet, the structural frame is made from glulam, with a concrete lift shaft and stabilising steel trusses.

The floors and roof use surface units in Kerto, a strong and stiff laminated veneer lumber made from spruce. The cavities in the units are filled with mineral wool that is designed as airborne sound insulation but also has good properties with regard to impact sound.

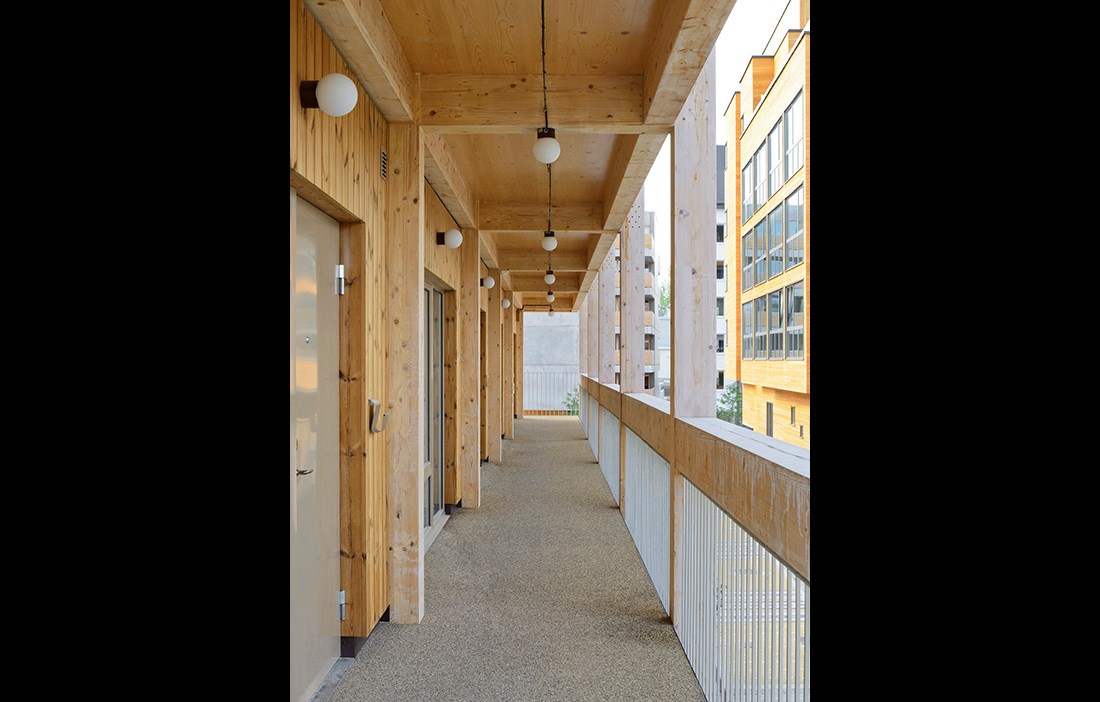

“The access balconies are entirely CLT and for the exterior cladding we’ve used durable heat-treated Thermowood. Overall, our material choices have led to a fast and flexible construction process,” states Ola Broms Wessel.

This was also helped by the fact that the access balconies and apartment balconies, which are suspended around the outside of the building like a girdle around its waist, were installed early on in the process. This meant they could then be used like scaffolding during the construction period.

With its roots in the ideals of Sweden’s Million Programme for public housing, Spridd has decided to tackle the need for simple and effective standard solutions that can deliver good housing at a reasonable cost. Träloftet presents a prime example that also uses a renewable material.

“We may well look back on Vallastaden as the great breakthrough for wood construction,” says Ola Broms Wessel.

Another example of an innovative wooden building from the housing expo in Linköping is Integralen 6, or Ivalla, which has been nominated for Building of the Year 2018. Sustainability and flexibility have been the watchwords throughout this project.

“Small-scale, personal and different,” is the headline from architect and builder Staffan Schartner, who wanted to build a building with a long lifespan that could develop as needs changed.

Schartner has had a long career in Austria, where the architect has a different role compared with Sweden, as project manager and construction architect. Inspired by previous experiences, Ivalla is the first project in Sweden where he has had full ownership.

“I wanted to build entirely in wood, with flexible electrical installations and plumbing, which meant that the technology and infrastructure got to inform the building’s architecture,” he says.

The result is an exciting look built around a strong post-and-beam glulam frame from Austria, which also supplied the CLT for the gables, the courtyard façade and the floor structure. The glulam elements of the façade were produced in Lithuania using Russian wood. Prefabricated bathrooms were purchased from Finland.

“The sourcing has been time-consuming. But it was the only way we could afford to build the design we wanted, with all our material choices rooted in an ecological life cycle,” comments Staffan Schartner.

The life cycle focus and strong eco-profile have also resulted in fibre-reinforced plasterboard on timber studs for the internal walls and wood fibre insulation on the external walls. The roof uses CLT and the balconies are made entirely from wood. To achieve the required flexibility with a completely uninterrupted floorplan, there are no load-bearing walls inside the building. Instead the CLT surface units on the façade support the building, with the floor structure suspended from beams and the balconies resting on posts. The external walls are designed so that windows and balcony doors can be moved

In addition, all the installations are easily accessible in a shaft in the gable end of the block and under hatches in the floor. This allows the building to easily be reconfigured. The kitchens and bathrooms can be moved and the number of apartments can be increased or decreased from the current 22, all of which have access to a balcony, to accommodate future needs.

“It has become an extremely flexible and at the same time sustainable building that can survive in a changing society. I’m very pleased with it. I think the nomination for Building of the Year is well deserved,” concludes Staffan Schartner.

Text Mats Wigardt