For a long time, the Austrian town of Güssing was a half-forgotten outpost not far from the rusting barbed wire fencing of the Iron Curtain. Change came in the mid-1990s, when the town found it difficult to pay its electricity bills and was forced to review its energy consumption. They quickly switched to alternative green energy and became the first region in the EU to cut their carbon emissions by 90 percent. Over the next few years, international investors and farmers flocked to the little green town to get a glimpse of the future. Today there is a sign at the side of the road as you approach the town: “Eco-Energy Land”.

When the agricultural college in the town needed replacing with a new one a few years back, it felt only natural to also give it a sustainable profile. As part of this, all the animal sheds would be modernised and built to strict biodynamic guidelines. When Pichler & Traupmann Architecten won the contract to design the college, they were not entirely prepared for how complicated it would end up being.

“Our initial thought when we came to designing the sheds was that it ought to be quite simple. But it’s more difficult than you might think. They have to follow a complex system of regulations that differ for different animals. But we like a challenge, and with a bit of creative thinking we managed to meet all the requirements,” recalls Johann Traupmann of Pichler & Traupmann Architecten.

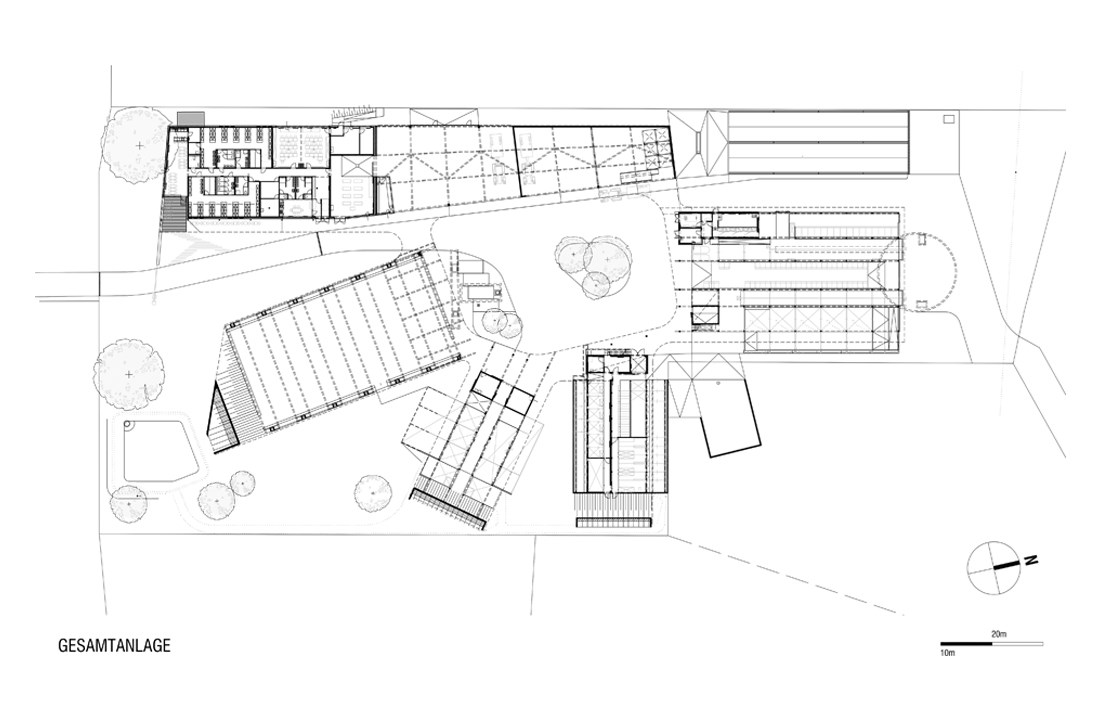

Ahead of the project there was an architectural competition, but while most entries involved conservative solutions that arranged the sheds alongside each other, Pichler & Traupmann came up with something completely different – which caught the eye of the jury. The inner courtyard has been placed centrally and the various parts of the college run off it like the fingers of a hand. The courtyard provides a good overview and easy access to both the sheds and the classrooms. This layout allows staff and students to carry out their daily work effectively. The design is practical for the flow of work, but the architects drew their main inspiration from the client’s requirement concerning the school’s new sustainable profile.

“Modern, biodynamic livestock farming includes requirements for good access to fresh air and sunlight and a strong link to the surrounding landscape. Creating a building with this finger design gives you more space between the sheds, so that air and sunlight can flood in freely. Plus it establishes an even clearer connection with the landscape,” says Johann Traupmann.

Viewed from above, it is hard to distinguish the college from the fields. Each section has a sedum roof, which makes it look like a series of small hills. Many parts of the town, not least the popular castle up on the nearby hill, look down towards the college site. For the architects, it was important to make the building part of the landscape and not disturb the view.

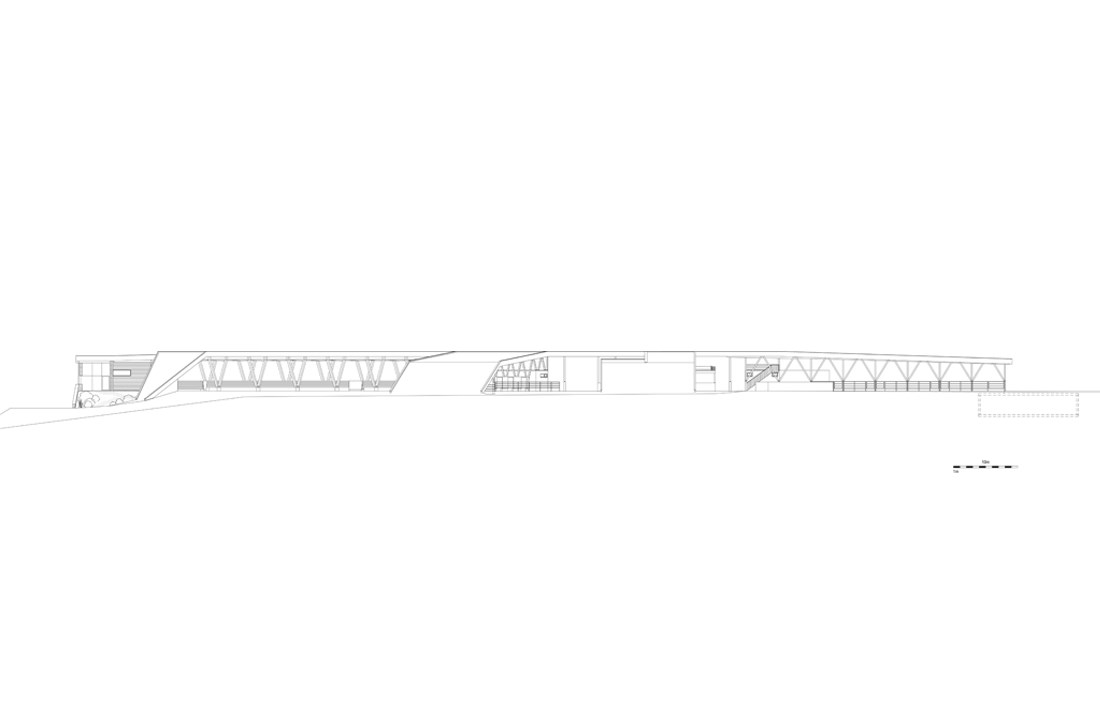

“Our idea was to cut out slices of the ground, raise them up and then build underneath. To a large extent, the project was as much about landscape design as architecture,” says Johann Traupmann.

In addition to functioning as a kind of camouflage, the key function of the roof was to insulate the building in an energy-efficient manner. However, the plantlife on the roof also brings savings when it comes to stormwater management. Another benefit is that the roof flows over all the buildings, providing good shelter from wind and rain. On damp days, staff and students can move between the various buildings without getting wet.

The roof structure comprises OSB panels that rest on primary and secondary glulam beams of varying dimensions, depending on the forces they have to deal with. The whole roof structure sits on V-shaped pairs of glulam posts with steel fixings attaching them to concrete foundations. The glulam is manufactured from local spruce. There are many reasons why the architects made such extensive use of wood. The old college was a brick building and they wanted to create something different and lighter. The fact that agricultural buildings are traditionally made from wood and that the college has a biodynamic focus also contributed strongly to the choice of wood.

“When you’re building something where animal welfare is so important, where everything they eat grows naturally in the fields, it seems obvious that the building should also use materials that grow in nature. It’s really sustainable. If, one day, the building has to be recycled, wood also makes that extremely easy,” says Johann Traupmann.

Austria’s wood industry is one of the country’s most important sectors, employing around 300,000 people. Although Pichler & Traupmann are not specific wood specialists, they are noticing a strong desire to broaden the way the material is used. This is being driven both by current thinking on sustainability and new techniques that allow wood to be used in bigger and more complex structures.

“The sawmill industry is a major part of our economy, which is why there’s such an interest in finding more ways to exploit it. It’s exciting to see how the material’s qualities are increasingly being put to use, in ever taller buildings. However, wood does place certain demands on the architect. Over the course of the project we learned, for example, that using the material requires extremely careful planning,” says Johann.

The students and the local residents like the new college. There is a riding arena that is open to the public and dressage competitions are also held here. The students like the open, light spaces, combined with the warm feel of the wooden structure.

“The building is an education in itself, you can see and understand how everything is put together. Whenever I visit the school, the students often tell me they didn’t think animal sheds and stables could look like this. I grew up in the countryside myself, and all I remember are dark, enclosed sheds with poor airflow. So it was fantastic to get to build something like this. The animals seem to be doing extremely well, and we’ve let them get even closer to their natural environment,” concludes Johann Traupmann.

Text Erik Bredhe