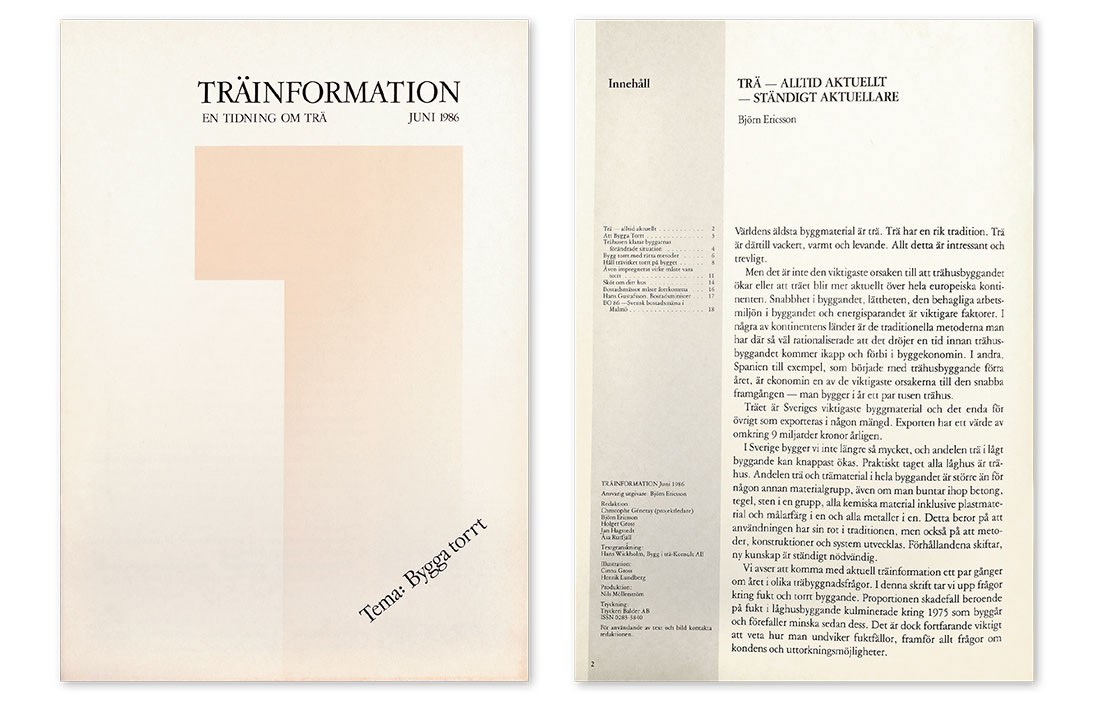

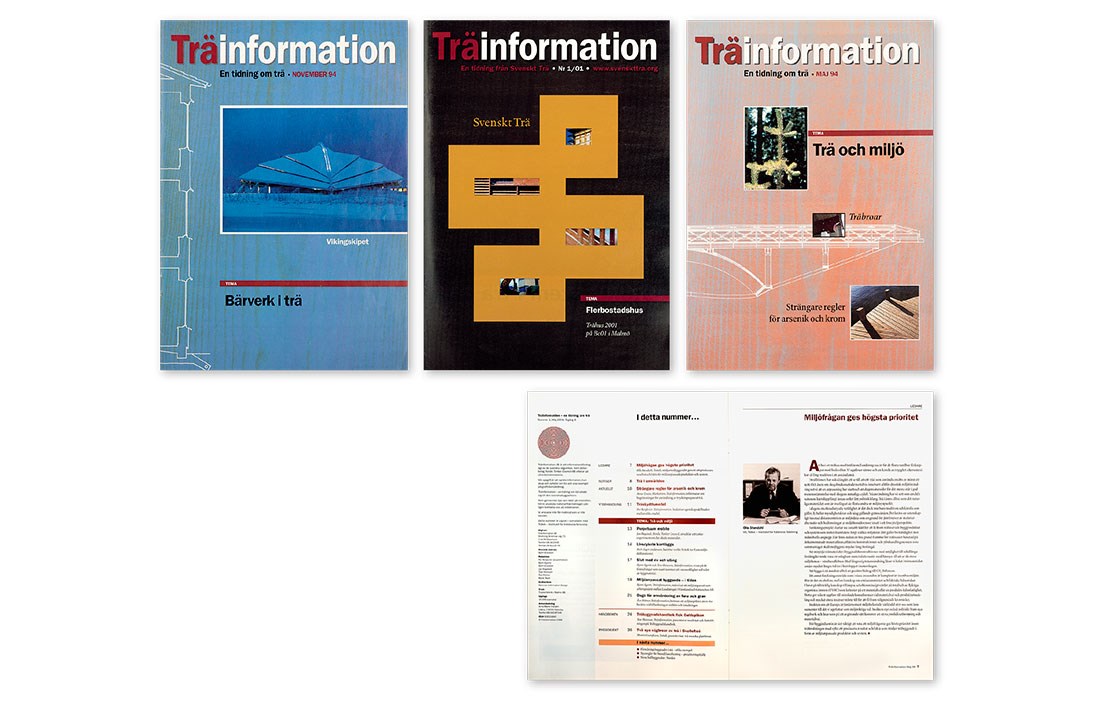

The first issue of Träinformation was launched in June 1986. With a remit to market and inform, it aimed to drive up the use of wood in construction. After seven years publication was suspended for a year, primarily for financial reasons. The following year, 1994, Träinformation was given an almost complete upgrade.

Taking the magazine to a new level proved a good tactic. Accession to the EU in 1995 brought a round of standard harmonisation that proved crucial for wood construction in Sweden: all building regulations would now be formulated as functional requirements rather than requirements for specific technical solutions. The building standards thus became material-neutral and that made it possible to build apartment blocks in wood that went beyond the two floors previously prescribed.

This paved the way for increased use of wood in the housing sector, naturally without ever compromising on fire safety, structural stability and other vital factors. The mid-1990s also marked a decade-long period of government initiatives and investments in the field, including wood research, wood construction and the development of wood products. Committees, reference groups and a range of collaborative projects were set up between the wood and construction industry, public agencies and organisations. For a few years in the mid-2000s, issues relating to wood construction were even raised in the Government Offices.

During this time, the magazine took yet another step to boost its relevance to the construction industry. An editorial board comprising representatives of the construction industry replaced the existing editorial team. More thought was put into the layout and the visual material in particular was given an upgrade This period became an intensive phase in the history of “new wood construction”. It’s no exaggeration to say that the showcase wooden building Trähus 2001 at the housing fair Bo01 in Västra Hamnen in Malmö marked a watershed in Swedish wood construction.

Swedish Wood prepared its participation in the fair by announcing an architectural competition. The competition attracted entries from 132 teams across Europe and was won by two young Danish architects, Kim Dalgaard and Tue Traerup Madsen. Several issues of the magazine examined many different aspects of Trähus 2001, and the exhibition catalogue took up one entire issue. The planning and construction of Trähus 2001 also provided insights into a range of difficulties that needed to be overcome if wood construction was to expand.

Development of materials, methods and processes

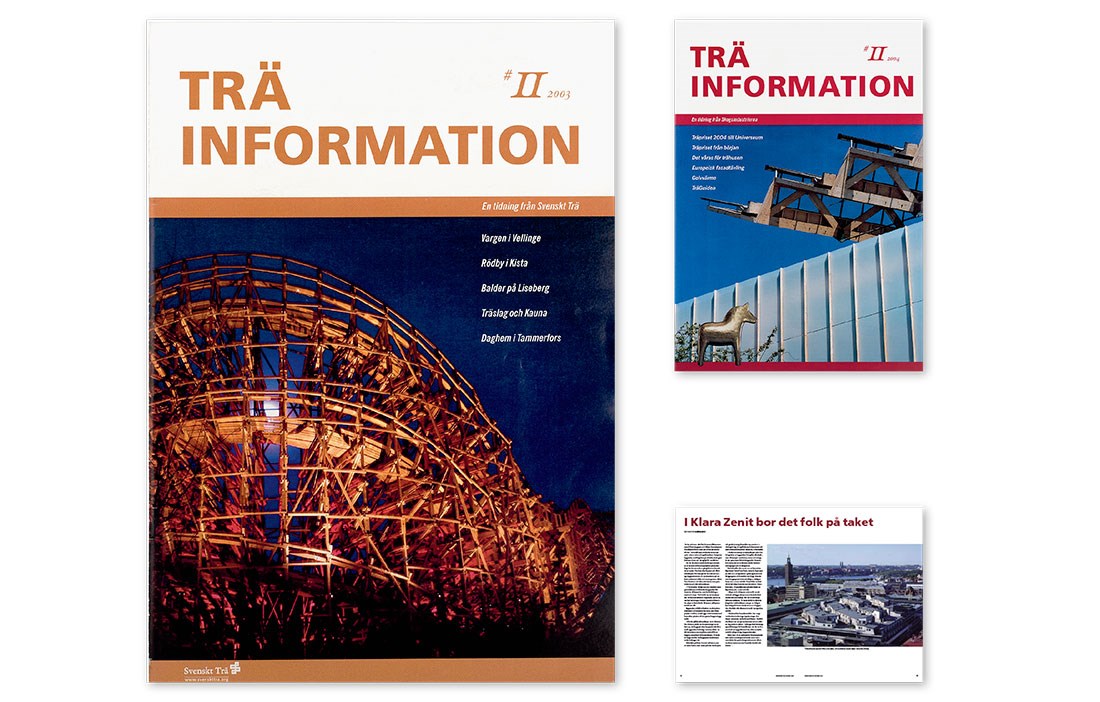

Trähus 2001 made little use of prefabrication, so showing how an industrialised process could improve the competitiveness of wood construction became a key theme in the magazine. Closely linked to this are issues of product and material development, not least as a result of the intensified R&D work since the mid-1990s. Although the advances may have come more slowly than expected, several companies have now industrialised their wood construction methods.

Wood in an urban environment

Cities in wood is an issue that met strong opposition. Maybe the old fear of city fires lived on, or maybe traditional wooden houses were seen as unsuitable for a modern urban environment. As a counter-argument, the magazine was able to present Universeum in Gothenburg, which also won the Swedish Timber Prize in 2004, along with several articles on wooden cities. Today, we’re seeing many interesting examples of how to design buildings in wood that fit perfectly into the cityscape.

Large structures in wood

Universeum can also be seen as an example of another area where we lacked modern sources of inspiration, namely large buildings with a wooden structural frame. Now there were legal opportunities, but where were the ideas and where were the practitioners? Universeum opened people’s eyes to the potential for public buildings with more than two or three floors. It soon became obvious that greater cooperation was required between architects and structural engineers – something that has been a direct or indirect theme in the magazine for many years. And again, considerable progress has been made in recent years.

Wood in interaction

The wood industry often espouses the theory that a wooden building should be a building where practically everything is made from wood; that the most wood wins. The problem with this became particularly apparent in larger buildings, where an inspired use of steel or concrete in the structures has allowed the creation of more slender and elegant architecture. With this approach, architects would be more likely to choose wood, driving up the use of wood overall. The four issues in 2011 therefore focused on how wood can interact with concrete, steel, glass and composites.

New wooden architecture

Finally an important experience. The winners of the architectural competition to build Trähus 2001 came from a country without any particular tradition of building in wood, and many of the Swedish entries drew heavily on the Swedish tradition of wood construction in terms of materials and designs. An important element of the magazine from then on was therefore to showcase wooden architecture from other countries in order to inspire the construction sector to think along new lines when it came to building in wood. And it seems like the message is getting across, since the diversity of wooden architecture has certainly increased.

We have now singled out five strategic themes that have run through the magazine over the past 30 years. Alongside this, the magazine has been an invaluable source of knowledge in the field of wooden construction, addressing moisture, façades, durability, façade materials, paints, traditional construction techniques, interiors, renovation, extensions, acoustics, environmental issues and sustainability.

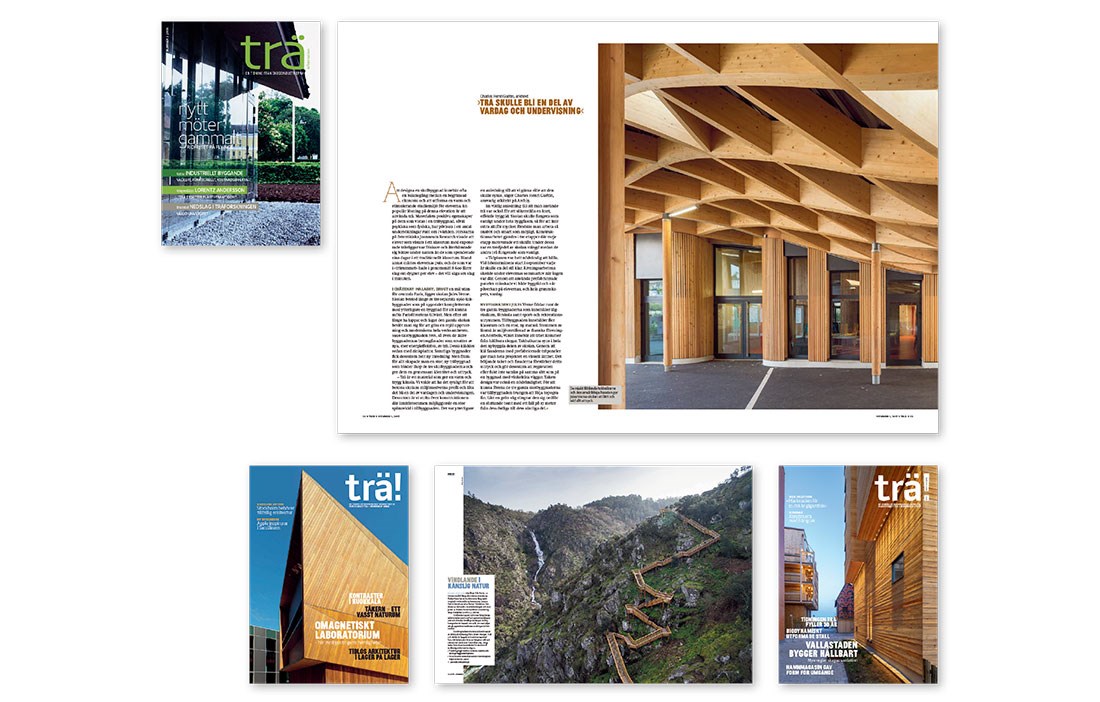

It is interesting to note that, since the early 2010s, the magazine has increasingly aimed itself at architects and structural engineers. Since the third issue of 2012, the magazine’s subtitle has been A magazine on inspiring architecture, a change that perfectly reflects the spirit of the time. The magazine is less thematic than it used to be. There is more of a focus on spectacular international projects, with larger and more suggestive images. The technical information may therefore have shrunk back a little, but plenty of this information is still available in digital form on the Swedish Wood website and other sites.

And the answer to the question we asked ourselves at the outset? We realise that far from existing in a vacuum, the magazine has navigated the currents of industrial politics, technical advances and international architectural trends and operated in collaboration with a large number of domestic and international players in the wood and construction industry.

Despite this, and despite perhaps partly preaching to the converted, we would suggest that over its 30 years, the magazine has been invaluable for the development of wood construction in Sweden.

Text Hanne Weiss Lindencrona