Renovation work on the floor of the old Wheelwrights’ workshop uncovered the timbers of one of Great Britain’s many legendary warships, Namur. The ship was built in the 18th century, when Britannia ruled the waves. The discovery launched a building process that last year culminated in a RIBA Stirling nomination for the restoration and newbuild project Command of the Oceans at Chatham Dockyard, designed by Banes and Mitchell Architects. The shipyard was the hub of Britain’s naval shipbuilding – from Henry VIII’s 16th century to Thatcher’s 1980s. Today, a foundation manages the 32-hectare site with 47 buildings that are Scheduled Ancient Monuments. The extensive project includes a newly built visitor centre, restoration, archaeological excavations and conservation of several historical monuments. It also involved restoring and adapting two adjacent halls, plus planning and preparation of the surrounding landscaping and car park.

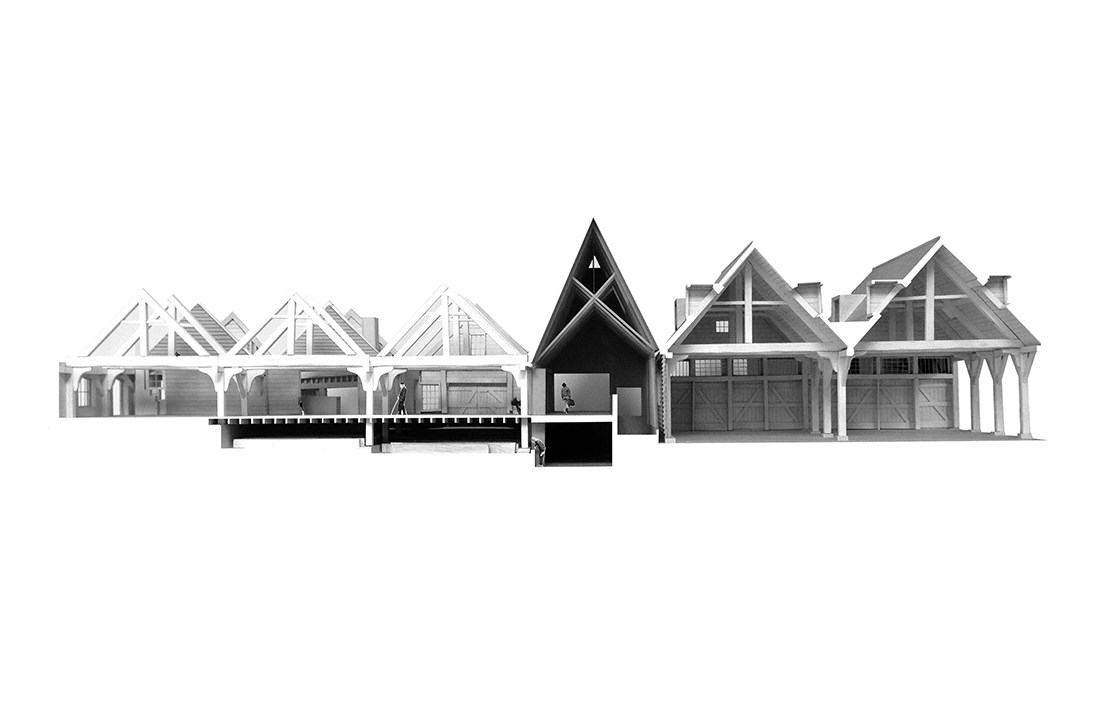

The focal point of the complex is the new black entrance building, with its austere zinc-plated façade and steeply pitched roof. The new building connects the neighbouring exhibition halls and leads visitors via a concrete ramp down beneath the floor of the Wheelwright’s workshop. And there lies the great archaeological find – the over two-centuries-old timbers from the warship Namur, just as they were found. The surrounding listed halls have been carefully converted into exhibition spaces, plus a café and museum shop.

“We worked on the exhibition design at an early stage in the project. It was important to establish a single vision for the exhibition within the building. But the buildings themselves also have a lead role in the exhibition, so the two aspects had to be combined into a cohesive narrative,” Alan Mitchell, co-founder of the practice, tells The Architects’ Journal.

Creating a cohesive narrative out of all the historical layers, while meeting modern demands concerning accessibility and services, required what in restoration terms was a bold reinterpretation of the circulation through the buildings. The level changes between the buildings and between the surrounding land and the buildings was used to create an inclined spatial sequence, where the landscape, buildings, exhibition and excavations together form an intricate story about the art of building ships and buildings in timber. The intimate interaction between old and new required not only a meticulous archaeological excavation, but also the construction of a temporary suspension bridge over Namur’s timbers. This was then used to build a new floor for the new level above.

Modern strategies for restoration – such as reversible materials and building components, protective surface finishes that retain patination, and new additions and joints that are precise and clearly signposted – bring to life Chatham Dockyard’s historical presence, sometimes through interfaces where the new frames the old.

The light that falls on the entrance building’s intricate pattern of scissor trusses creates a striking feature in dialogue with traditional construction techniques. The varied use of wood, in modern panelling, decorative concrete shuttering, laminated sheets or structural timber, both accentuates and bridges the gap between past and present.

By binding time’s different expressions of the same material to each other, we are reminded that time is a process of constant change.

Text Lars Ringbom