With its 3D-modelled free form, Paneum could be mistaken for a spaceship that has landed near the Austrian city of Linz. As the steel-clad façade sparkles in the light, it is hard to comprehend the level of innovation in wood construction that this building exhibits. It comprises two parts: a boxy concrete volume housing conference facilities and attached to that an exhibition space that accommodates bakery magnate Peter Augendopler’s own, very personal, homage to bread – a museum of its history and its influence on food, culture, art and life. The name Paneum combines pan, which means bread, and eum, which stands for museum. It is therefore only natural that many see the shape as a lump of dough or a loaf.

“It’s a combination of a cloud and a ship, a modern kind of Noah’s Ark. In the Ark, Noah collected things that they wanted to save for a new world, and similarly we want to preserve and display the history of bread,” says Wolf D. Prix, chief architect at Coop Himmelblau’s Austrian office.

The very first meeting with the client prompted an idea about what kind of building he wanted to create, following Peter Augendopler’s impassioned account of bread’s history and importance and of his desire to set up a museum. Based on this, Wolf D. Prix sketched a rough draft that still exists today, and it was this that the team of architects used as the basis for the final design. Much of the end result can be traced directly back to that sketch. And it was the reference to Noah’s Ark that sealed the deal for the use of wood. No other option felt appropriate.

“The Ark was wooden, so of course Paneum also had to be. In this case, the material gives the intimate feel that we wanted. It’s not a traditional museum with huge empty spaces. We wanted to create a cosy atmosphere. I therefore suggested that, through its design, the building would form a cultural centre, a place for discovery and exploration, with a more personal touch than a traditional museum.”

Paneum’s design is not just a cool structure, with clear references the Guggenheim Museum in New York, that tickles the creative tastebuds and encourages a thirst for knowledge about bread. Above all this is the world’s first free-form wooden structure, an object that was once thought impossible on this scale. But Wolf D. Prix asserts that it was no more difficult to create the shape in wood as it would be in any other material. All it took was a good dose of imagination and some blue-sky thinking.

“Ask the architects who only make boxy houses and rectangular buildings what’s holding them back. Everyone said this would be difficult, but we convinced them that it was possible. I don’t know the word ‘impossible’, it’s not in my vocabulary. Instead, you need to understand that you can’t solve complex problems using simple solutions. You need to seek out more unconventional solutions to make it work.”

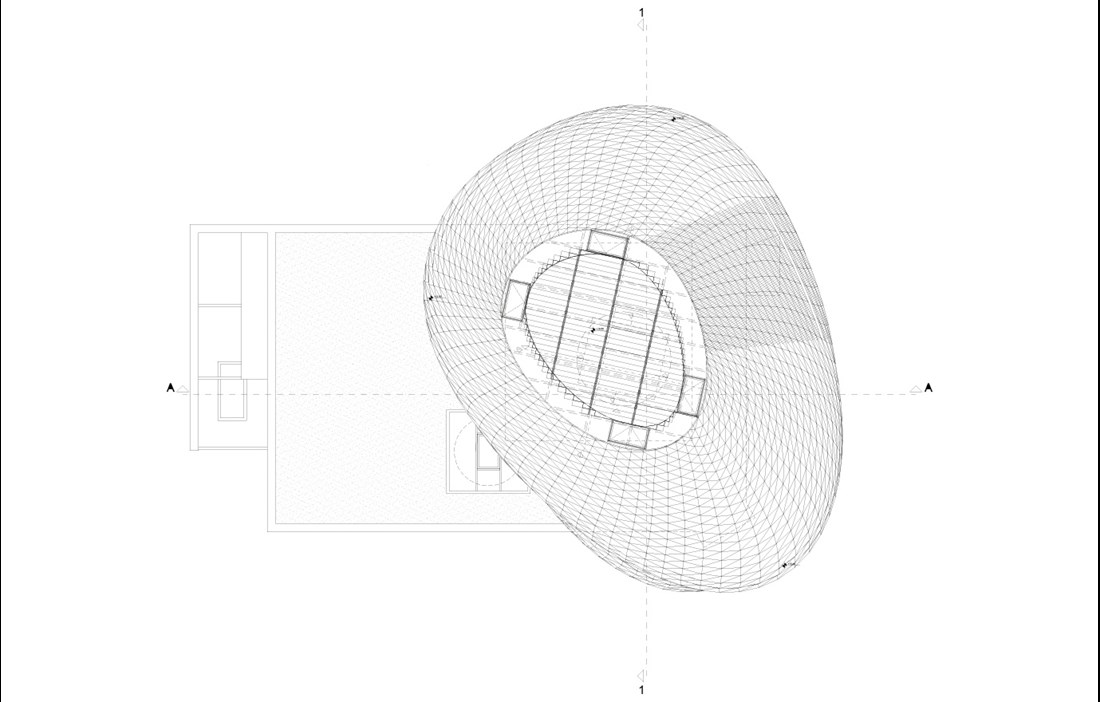

To make the irregular shape possible, the architects worked with 3D and CNC technology.

“We always work with modern technology and in 3D. First of all, we sketch out what we want to do and then we create a miniature model of the sketch in 3D. The technology, and what it can help us to achieve, is one of my great architectural interests.”

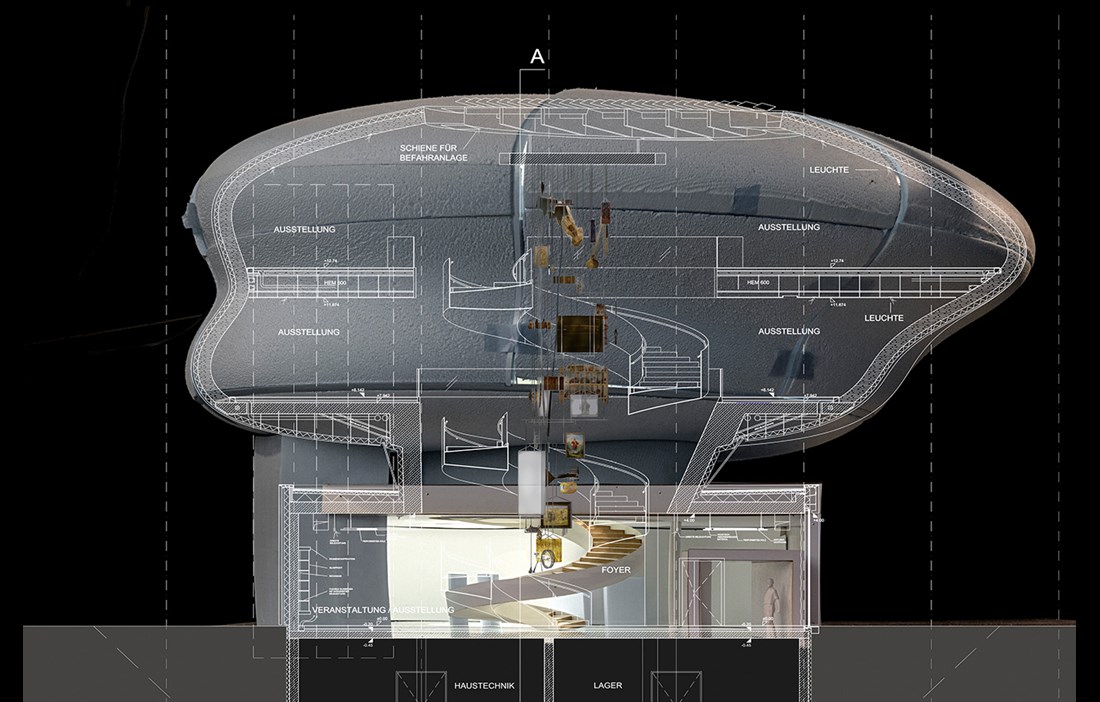

By modelling the design, they were able to check on the drawing board that everything worked properly and they knew, before the actual construction process, exactly what everything would look like and how it could be built. This also ensured that the prefabricated CLT components, locally produced in spruce, could be put together with millimetre precision. It was like a huge kit, where every piece fits into the next one to form a stable structure. The length varies between 4 and 12 metres and, with the help of an algorithm, the joints have been positioned to provide optimal load-bearing capacity and structural strength.

“The frame is made from rings cut out of CLT sheets that were stacked on top of each other to form a kind of pipe structure. This was then secured in place using long wood screws. It’s self-supporting and doesn’t need any posts. This design makes it possible to create an open space, similar to the hull of a boat. There are no support pillars, just horizontal structural components.”

But the technology hasn’t just delivered the impressive shape that Paneum displays today. Having everything pre-prepared down to the smallest detail made construction more efficient and the construction time shorter. It took 6–8 weeks to cut out the CLT and its assembly took 4 months.

Externally, the façade also attracts attention via the 3,000 silvery tiles in stainless steel that cover it and constantly bounce the light around. As it turned out, this part of the project was a little more time-consuming.

“Since the company was unfamiliar with robot technology, they had to fit each tile by hand. Of course that takes longer, so once they’ve learned to use robots, other projects will be easier,” says Wolf D. Prix.

If the outside poses questions, the inside has all the answers, showing how everything hangs together, how the apparently impossible has proven entirely possible. In the interior, the CLT has been left clearly exposed and combined with concrete and glass. The spiral staircase that joins the two floors in the 20 metre high wooden section of the building provides an overview of the exhibition space and contributes to the sense of being in the middle of a tornado. The shape is as striking as the massive collection of objects relating to bread, including a mill from Egypt that is over 1,000 years old. The walls are lined with art showcasing the various ties between humanity and bread.

“You can’t hang paintings on a curved wall, so we’ve suspended them from the ceiling instead.”

And visitors love the experience.

“I think we’ve done a good job. Paneum has had over 10,000 visitors in its first six months, despite not being in a major city or having any other attractions nearby. It’s a huge success.”

Text Johanna Lundeberg