An almost sacred elegance lingers over the two houses outside Heidelberg. Like two geometric wooden blocks, they follow each other’s lines on the steep site. The brief was to design two detached homes on the long, narrow plot, nestled in amongst houses built between the turn of the last century and the 1950s.

“The buildings echo each other, with a similar structure and design language, but in different sizes. They have also been offset vertically and horizontally to offer views of the surrounding village and to create private areas that are not overlooked,” says architect Alexander Marek.

Both the client and the architect genuinely love wood. But it was still a big step to embrace an entirely wooden house.

“The house was initially going to be built in brick – that was the only option on the table.”

But the plot’s challenging topography proved more suitable for a wooden house that could be designed in 3D. A structural engineer who could master the machines in the factory was brought onto the project team. Costings for various alternatives showed that brick would be the cheapest. CLT was the most expensive.

But by then, Arklab had already planted the idea of two sibling hillside houses in untreated wood and site-cast concrete. And despite the cost, that was the idea that won the day.

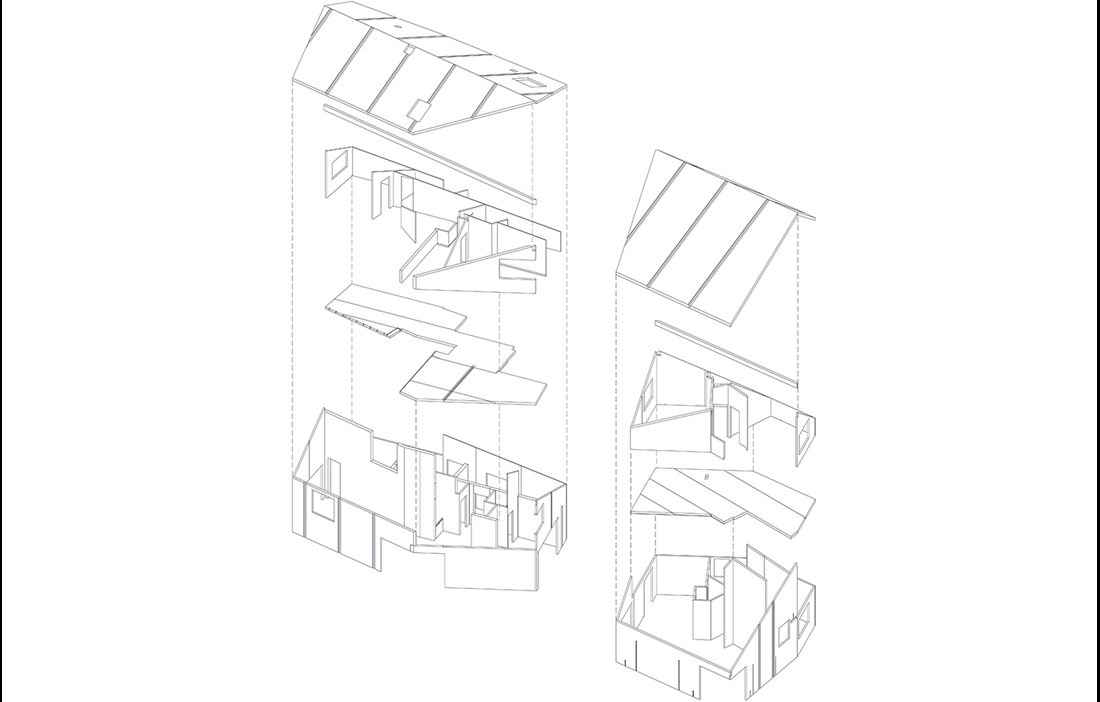

“The wooden houses were built on a cast concrete level set into the hillside. A central concrete wall then goes all the way up to the ridge, supporting the roof and providing stiffness against wind load. Everything else is wood: the frame uses solid CLT in the floors, roof and external and internal walls. Plus the insulation is wood fibre,” he adds.

The choice of material did, however, throw up some problems that had to be resolved. Such as adapting the precision CNC-cut wooden frame to the site-cast vertical concrete structure with its relatively large tolerance of 20 millimetres. The connection points in the façade also had to be fully windproof.

“But the biggest challenge in Germany is the summer heat. During the summer months you can get several weeks when the temperature hovers around 40 degrees,” states Alexander Marek.

They solved this issue by fitting almost all the windows with folding and sliding shutters in aluminium and then finishing them with cladding to match the façade. The wood fibre-based insulation was chosen to ensure a homogeneous blend of materials and for its excellent ability to protect against heat. The solution for the two corner windows that are such prominent features of the façade is special glass with higher solar control values.

Both houses were completed a while ago and are now occupied by happy owners and tenants. And it seems that interest in wood construction is growing in Germany, where the costs are considerably lower than in Sweden, despite a higher proportion of site-built houses.

“The houses we built in Heidelberg would have been around 60 percent more expensive to build in Sweden, despite Sweden using significantly more prefabricated components, and that’s a figure that applies across the construction industry generally,” says Alexander Marek.

He believes one of the reasons for the big discrepancy is the many links in the chain in Sweden that all take their cut. Another explanation he suggests might be the different role of architects in Germany, where they are the formal developer during the construction period and the project manager, a role that in Sweden is usually taken on by a construction company.

Another key difference between the two countries that Alexander Marek highlights is the connection with craftsmanship that lives on to a greater extent in Germany, as well as a curiosity to try new things.

“In Sweden, people are often more sceptical about these kinds of challenges. At least right now.”

Text Mats Wigardt