With the loss of the fur trappers and whaling ships from Svalbard, tourists and researchers are the main visitors to this remote group of islands, 1,500 km north of the Arctic Circle and halfway between Northern Norway and the North Pole. The majority of the islands’ 2,500 inhabitants live in Longyearbyen, Svalbard’s administrative centre. Somewhat further north, at a latitude of 79 degrees, lies Ny-Ålesund. In the 1960s, the former mining town in western Spitzbergen was transformed into an international research community, forming what is now the world’s most northerly settlement of permanent residents. 30–35 people live here all year round, and in the summer the population rises to around 120. Most of them are researchers and technicians.

According to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), average temperatures over the past few centuries have risen twice as quickly in the Arctic as in the rest of the world, and this is what has drawn climate researchers from around the globe to settle here. Today, the research community is described as the backbone of the local economy in Svalbard.

Ny-Ålesund has 17 research stations staffed with researchers from 10 or so countries. The most recent station, the Earth Observatory, was opened in June by the Norwegian Mapping Authority, in partnership with NASA in the US.

The observatory’s two dishes can receive signals from remote celestial objects, quasars, 13 million light years away, which makes it possible to precisely measure the Earth’s movements, rotation and location in the universe.

“This will make Ny-Ålesund a cornerstone of the global infrastructure for more accurate monitoring of key processes such as melting ice sheets and rising sea levels,” explained the head of the Norwegian Mapping Authority, Per Erik Opseth, at this summer’s inauguration.

The new research station includes a powerful laser from NASA that is able to measure with extreme precision both melting ice sheets and the position of satellites circling the planet. The task of designing the station’s buildings went to Norwegian firm LPO Arkitekter, which has an office in Svalbard.

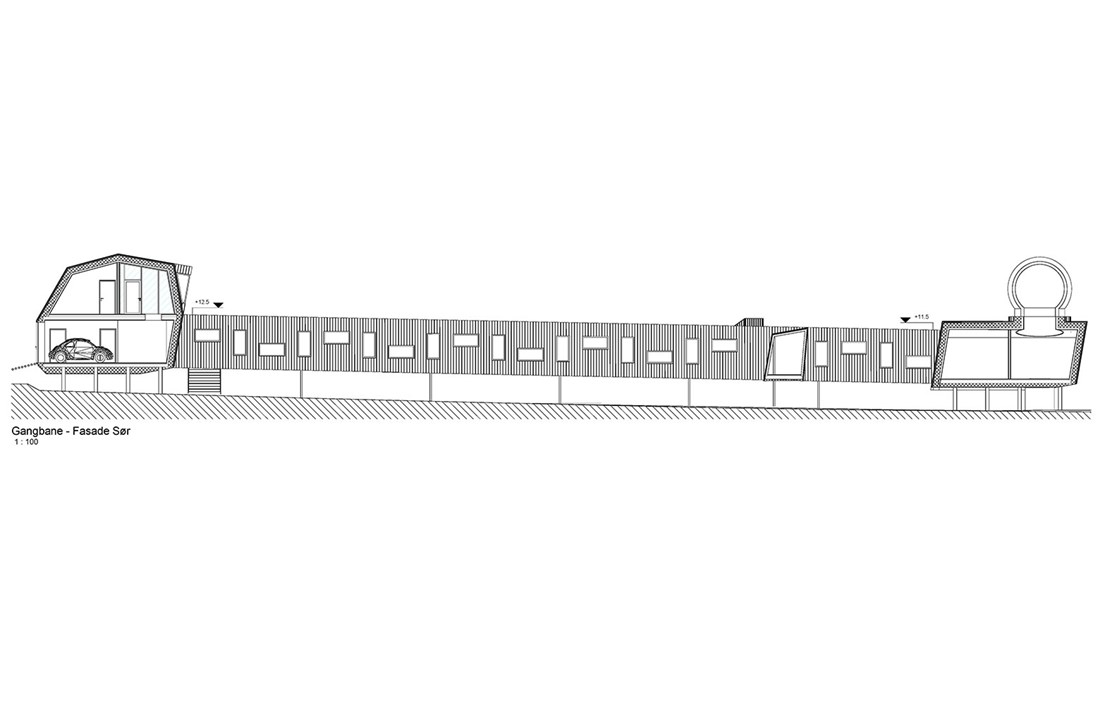

The Earth Observatory, part of a global network of research stations, comprises five main elements: a station building, two large dishes, a building for laser instruments and one for instruments that measure the Earth’s gravitational field – a gravimeter. All the buildings, with the exception of the one housing the gravimeter, are connected by an enclosed walkway.

In order that the heat from the buildings does not start to melt the permafrost, all the buildings are raised at least a metre above ground on steel piles anchored into the rock. The gap between the ground and the buildings also means that plants and animals are affected no more than is absolutely necessary by the project’s presence in this fragile landscape.

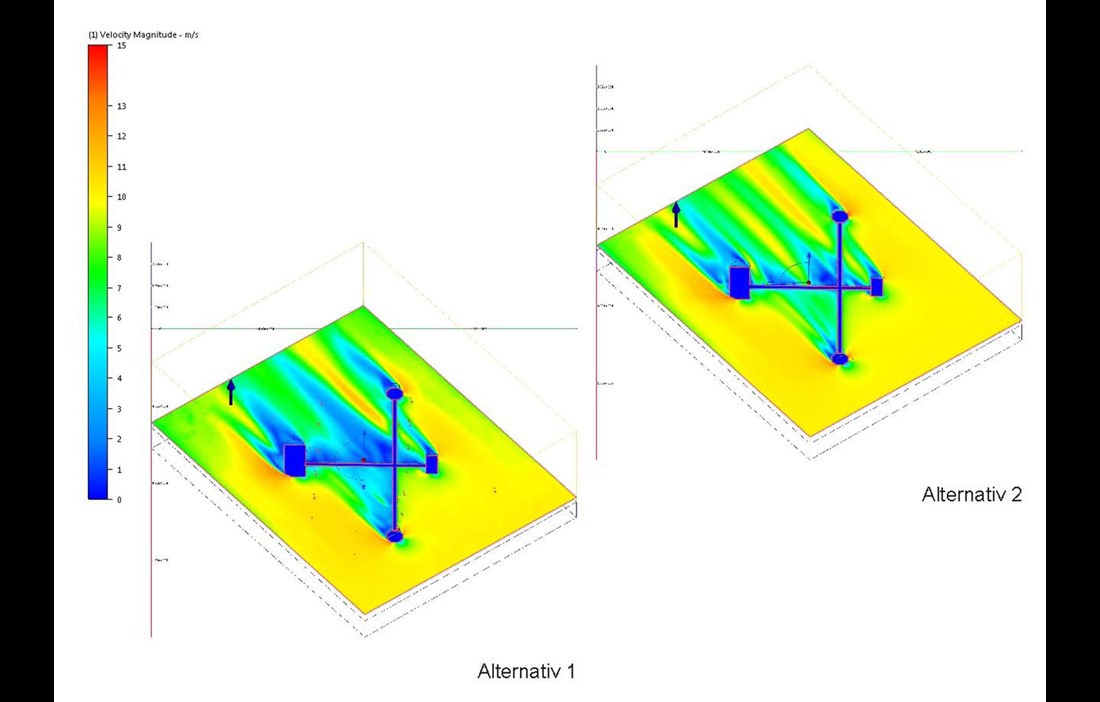

Following meticulous analyses of wind and snow drifting, the building has been given a cruciform shape and positioned so that the snow doesn’t form drifts that block doors and windows, and doesn’t collect beneath the blocks either. The entrances face south-west, since the prevailing wind direction is a south-easterly.

All the buildings have a considered asymmetric form, with their façades shaped to improve their aerodynamics – an important feature in a location where the weather is becoming increasingly extreme.

The station is built around a structural frame of mass timber that is made from three layers of boards screwed together with offset joints, in combination with glulam and steel beams. The building is insulated all around with a 360 mm thick layer of mineral wool. The exterior is finished with untreated slow-growing spruce cladding of various widths and thicknesses. The irregular surface of the façade creates friction with the wind and weather so the building will silver unevenly. Spruce cladding was used because in this case it was judged to be the most eco-friendly façade material.

Wood was chosen as a construction material for several reasons. Arvid Rønsen Ruud, Project Manager for LPO Arkitekter, explains that they took into account the lower transport costs, since all the material would have to be shipped to Ny-Ålesund by boat, the simpler logistics, the considerably shorter construction time and the obvious environmental benefits.

“Wood weighs just 20 percent of the equivalent components in concrete. Considering Svalbard’s heavy transport costs and demanding logistics, this was a crucial argument in wood’s favour. It will be left to silver at its own pace in the wind and weather and melt into the landscape over time,” he relates.

The station building is the beating heart of the outpost, housing all the facilities needed to run the research station. The first level has a garage, a workshop, a utilities room and rooms for freshwater and a septic tank. All the rooms have direct access from outside.

The second level contains the control room, from where the operator has a clear view of both dishes and visual contact with the adjacent computer room. There is also a break area and a small kitchen. The station is not intended for round-the-clock operation, but there are facilities for staying overnight if an emergency situation arises.

The Satellite Laser Ranging (SLR) building is accessed via the enclosed walkway. In the laser room, the laser cannon has to be mounted on its own plinth, entirely independent from the rest of the building structure. Above the laser cannon is a dome that needs to be strong enough to open even when covered with thick ice during Svalbard’s frosty winters.

Finally there is the gravimeter room, a separate building that is reached via steps down to a shelter from where you can look in through a large glass window. There are three plinths for the instruments in the room, all fully detached from the rest of the building.

The walkway that connects the various parts of the research station is entirely enclosed in part to keep it comfortable during the long winter, but also to protect the local wildlife and landscape from the ongoing human activity. In addition, a heated environment is needed for the cabling between the satellite dishes and the control room.

Windows of different shapes and sizes flow in a wave along the façade of the walkway, as what is probably the project’s only feature where function has taken a back seat to decoration.

All the systems that make up the new research station in Ny-Ålesund are expected to be fully up and running by 2022. And by then, the façade will no doubt have had time to turn an attractive silvery grey.

Text Mats Wigardt