When fuel station magnate Arne Sandberg donated ten million kronor to build Billingehus, it became Skövde’s leading architectural landmark. The leisure centre sits atop Billingen, Skövde’s almost 300 metre-high hill, looking out over forests, lakes and wild countryside. However, a number of buildings in another area of natural beauty have recently begun competing for the Modernist giant’s crown. These form the wooden development of Frostaliden, with its blocks rising up like short stumps in a high clearing on the edge of the forest. The residential area is part of ‘Wood City 2012’, a joint project by 16 municipalities to cut the environmental impact of the construction sector.

For Jan Larsson, chief architect at White Arkitekter, there was never any doubt that their contribution to the project would be built in wood.

“Sustainability and health are becoming key influencers in modern life. We think about what we eat, how we travel and shop. It’s also starting to inform housing choices, with many people keen for healthy living in an attractive wooden building,” says Jan Larsson.

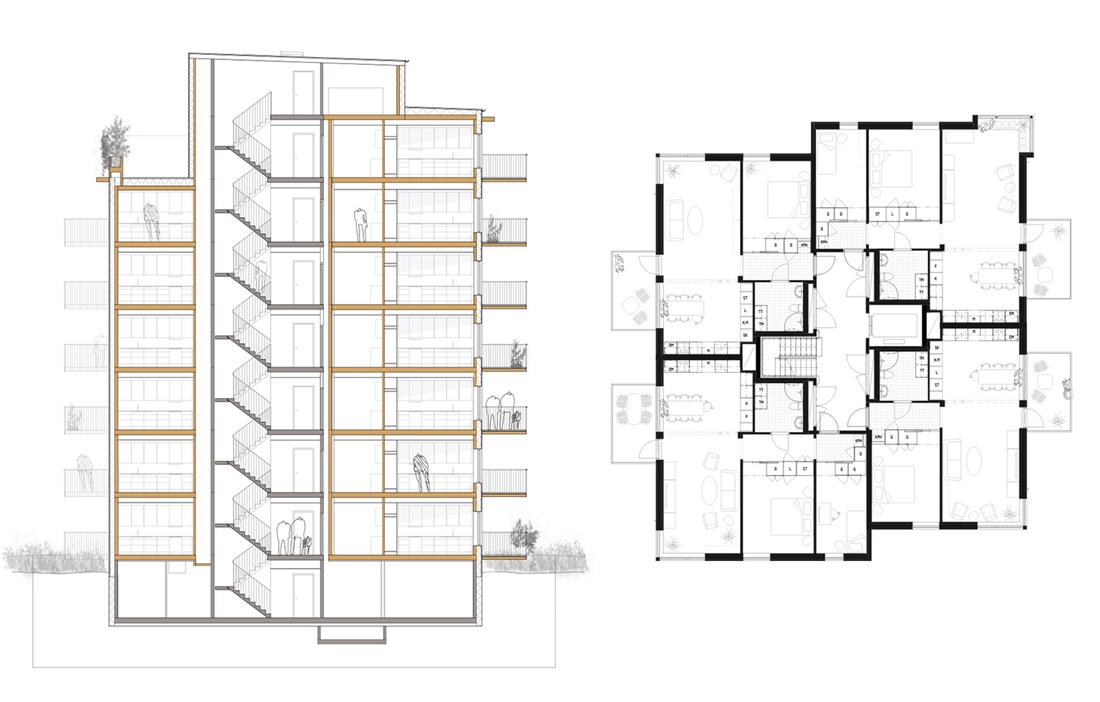

With the exception of the foundation slab, basement, basement floor structure and stairwell, the two eight-storey tower blocks are constructed entirely from wood. Environmental and energy considerations were also given as much consideration as possible in the choice of other materials.

The structural frame is made of spruce CLT. This strong wooden carcass makes the building’s walls self-supporting, enabling the architects to place openings for doors and windows practically anywhere in the building – in the façade, inside apartments or in the corners. They were are also able to create protruding bays by simply allowing the mass timber core to extend outwards.

“Working with CLT provides the architect with incredible freedom. Few other materials are quite so versatile. It behaves almost like prefabricated concrete, but weighs significantly less. I’ve always thought the two industries could learn a lot from each other, but unfortunately there is still a certain amount of resistance between them. I hope that will change in the future,” comments Jan.

It was important that all the wood, inside and out, remained visible. While meeting all the requirements concerning fire and acoustics, the aim was to keep as much as possible of the wood in the building exposed. And largely untreated. Instead, sprinklers were installed in all the apartments, following the example of office blocks.

“The sprinklers meant we avoided having chemicals on the walls, plus there is some uncertainty about how long fireproofing treatment actually remains effective. Our sprinkler solution was cost-neutral compared with fireproofing treatment, but with what we feel are several benefits,” says Jan.

The façade is clad in Canadian cedar shingles. The stunning patchwork comprises around 30x50 centimetre rectangles that are fitted by hand. The cedar shingles are maintenance-free, last a long time and have natural protection against rot. The architects therefore left the façade fully untreated.

“Cedar has many excellent properties, not least its appearance and the way it ages. We thought about the buildings as pine cones, or stumps, standing here on the Billingen hillside. Since the cedar shingles are fitted piece by piece, they can also be replaced individually if necessary, instead of having to remove a large area.”

The initial idea was for the whole façade to be wood, but during the design phase new fire safety regulations came into force, stating that large wooden buildings must be non-flammable from ground level up to three metres. The architects thus faced the choice of either fireproofing the buildings at the bottom or finding some other solution. Treating the buildings would have created a colour contrast between the shingles, which was not ideal. Instead, they opted to fit sheets of heavy-duty corten steel around the base. Over time, the steel will take on a grey-brown, matt patina that will match the silvering of the wood.

The client and architects held long discussions about what material to use for the lift shaft and stairwell. On the drawing board, the stabilising core was made of wood, but a subsequent compromise changed that to concrete. Once the decision had been made, Jan Larsson decided to exploit the contrast between the materials – and make it even stronger.

“We kept the stairwell really raw, not painting it or doing anything to it. So when you open the wooden doors and move from this austere, rough space into the light, wood-scented apartments with their beautiful oak floors, the contrast is magnificent. This way, the wood makes an even stronger impact.”

Mixing a living material with an inert one involves having to make certain adaptations. Wood is strongest along the grain, with less resistance across the grain; although the amount of compression is only 4–5 mm per storey, in an eight-storey building this can be a problem. Structural engineers resolved this by turning some of the blocks in the floor structure so that the wood resting on the concrete is end wood, which doesn’t shrink to any great degree.

Fristad Bygg was the turnkey contractor for the project and designed the CLT structure. Adam Kihlberg, CLT designer for Frostaliden, feels that the collaboration with the architects worked well.

“They had a good understanding of the whole project and a brilliant idea about the placement of the walls, which meant that we got the load lines into good positions,” he explains.

All 52 apartments in the two blocks were sold off plan and they are now ready to welcome their new residents. Jan Larsson is cautiously optimistic about the future of wood in large-scale buildings in Sweden. He has seen growing interest in wooden buildings over the past few years – not least against the background of the current climate debate.

“If we are to achieve the climate objectives, there are no shortcuts. We have to begin constructing more tall buildings in wood. We’re working on research projects for designs with as many as 22 storeys and are currently building an 18-storey block in Skellefteå. What we need are more good examples of attractive, cost-effective wooden buildings, of the kind we see in Austria and Switzerland. To show that we have the raw material, the drive and the craftsmanship.”

Text Erik Bredhe