The nine-storey block in the Kajstaden development begins as impressively as it ends. The oversized ground floor, which is designed to give the building an urban feel, contributes to the impression of a building that sits comfortably in its surroundings.

“We wanted the building to have a clear beginning and a vertical end that creates tension and elegance. At the very top, there are two floors with higher ceiling height and different roof shapes that set them apart from other buildings and create an exciting silhouette,” explains Ola Jonsson, the chief architect on this project and an associate at C.F. Møller Architects.

The block is one of the first in the district that is currently emerging as an extension of Västerås city centre. This new development will comprise around 700 apartments, plus squares and marinas, all of which are connected to the adjacent green spaces. A strong emphasis has been placed on designing the building so that it takes account of the site’s qualities on the shore of Lake Mälaren, with views of the water, the city and an expansive pine-clad landscape.

“The large amount of glazing and the framed balconies facing south-west give the apartments a generous amount of daylight and contact with the wider area. The building’s height and architecture make it a landmark for the new district, as well as a beacon for what can be achieved when it comes to sustainable building,” says Ola Jonsson.

The brief for all five of the buildings that C.F. Møller designed for the area stated that they had to at least have a wooden façade. However, after joint discussions, the decision was taken to build the tallest building entirely out of wood – and to do so without any compromises.

“Neither the developer nor the contractor had built in wood before, but they were determined to go all in. As a result, the walls, floors, balconies, lift shaft and stairwell are made from CLT. With the exception of the foundation slab, there are no load-bearing concrete elements anywhere in the building,” states Ola.

Practically all of the structural frame was produced at Martinsons’ CLT factory in Bygdsiljum outside Skellefteå. The high degree of prefabrication meant that it only took three days for three people to assemble each floor. The structural system developed here now forms the basis of Martinsons’ new model for custom frames for apartment blocks. Compared with previous models, this involves greater refinement of and focus on the structural frame, since that appears to be in demand.

“Contractors are used to building onto the frame, and this makes opting for wood less of a leap than it would be if a higher degree of finishing was required. We are also pleased to be able to offer a structural system that is so efficient and at such a price point that the public housing sector is also interested,” says Daniel Wilded, Product Manager at Martinsons.

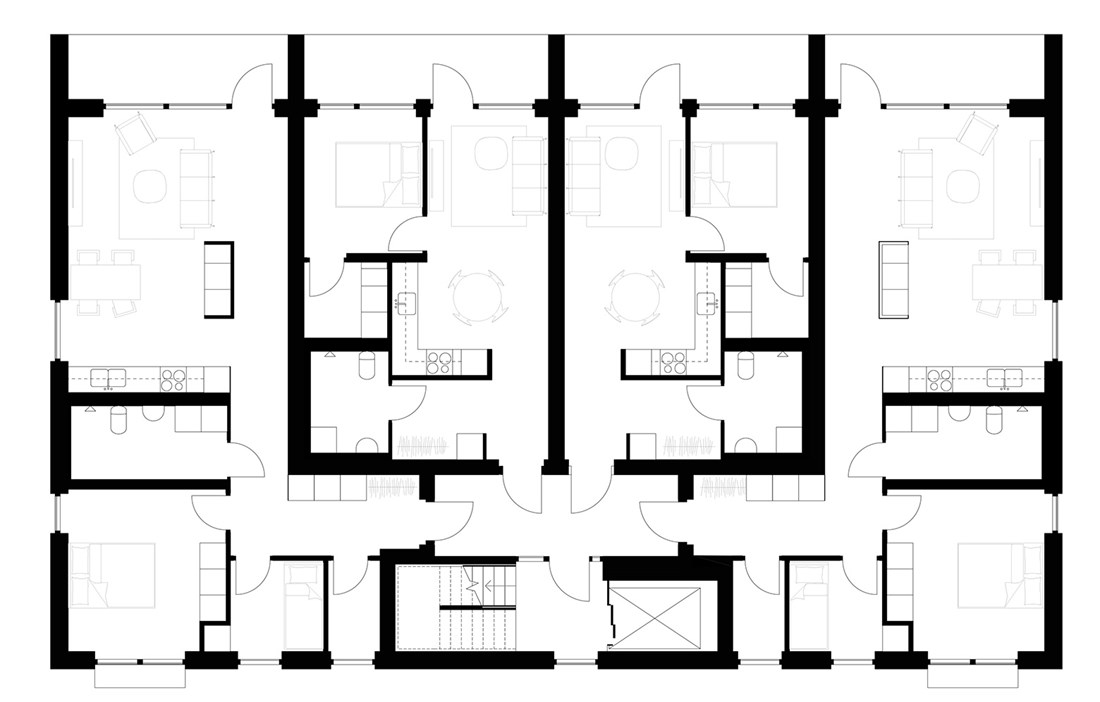

The CLT frame channels wind load, snow load and imposed load down to the ground via walls and floor panels. To avoid intrusive crossbeams interrupting the glazed façade facing the water, frame-stabilising walls behind the refrigerator and extra dividing walls have been added. The double party walls in CLT are a few centimetres thicker than double stud walls would have been. The result, however, is an extremely stable structure that is easily able to withstand the wind loads that the narrow building is exposed to.

“As the block is so tall, with such high windage on the long side, stud walls would not have worked anyway,” states Daniel Wilded.

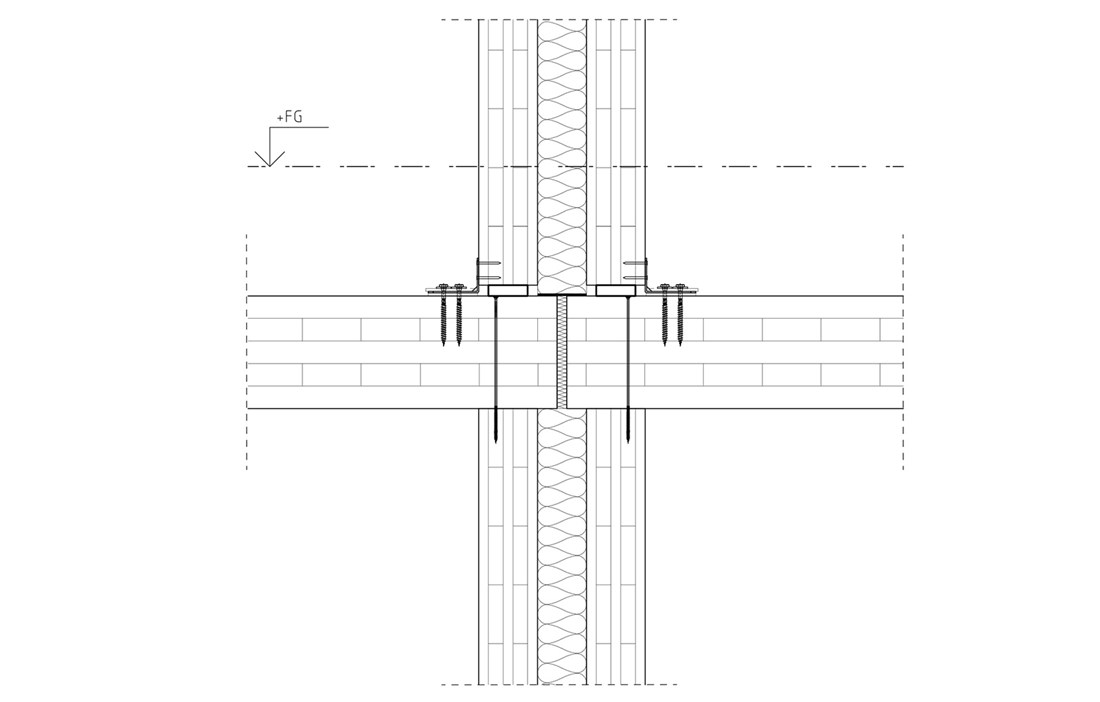

Another significant detail for the structural system is that installations and cables run beneath the flooring rather than behind a suspended ceiling. On top of the CLT floor structure sits a floor joist system from Granab packed with mineral wool sound insulation, which in turn is topped with a regular layer of flooring. The chosen solution also means that the system meets the criteria for sound insulation class B.

For the purposes of fire safety, the stairwell has a TR2 safety classification and serves as an ‘airlock’ between the staircase, the lift and the entrance doors. There and in the apartments, the surface layer of the walls is plastered and painted.

“The main reason that we haven’t used wood for the interior is that we don’t have sprinklers and right now the insurance companies are relatively restrictive when it comes to tall wooden buildings. So far, there have been no serious fires in wooden buildings with mass timber frames and the few fires that we have seen occurred primarily on construction sites, before the fireproofing was in place,” says Ola Jonsson.

The façades, on the other hand, are finished with heat-treated wooden cladding that has been stained black. The exception is the inside of the balcony frames, which have untreated cladding and play a key role in the overall architectural look. The design of the flashing for rainwater run-off along the bottom edge of the balcony forms another attractive aesthetic detail. The balconies and their frames are self-supporting and built entirely from cross laminated timber.

“By far the most interesting element of the frame solution is not the floor structures themselves, but what it looks like at the point where they meet,” says Daniel Wilded.

He doesn’t want to reveal exactly how this works. However, there has been a core focus on only using mechanical connections and wood screws, sometimes reinforced with nail plates, to make it easy to dismantle and recycle the components once the building has reached the end of its life.

“I’ve been involved in a collaborative group which the Swedish Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation has tasked with developing strategies for a move towards a bio-based circular economy, which fits in nicely here. The goal is to build as much as possible using bio-based materials that can also form part of an eco-cycle. Once the building has served its purpose, it can be dismantled and perhaps used in a simpler building or, moving down the chain, converted into simple building materials such as particleboard or, moving down again, into more fibre-based materials such as textiles and paper pulp and, at the bottom of the chain, used as biomass or fuel for incineration,” says Ola Jonsson.

He, Daniel Wilded and Erik Dansbo, investment manager for the developer Slättö Förvaltning, have seen a growing interest in properties with a clear sustainability profile. And the new nine-storey block is no exception, having just been snapped up by property company Balder and the Third AP Fund.

“The time has come to consider how we can build as efficiently and ecologically as possible. The production of a building accounts for a large proportion of the overall carbon emissions over its lifetime. Here we had an opportunity to do something cutting-edge and create an apartment block that is sustainable for the future,” says Erik Dansbo.

Building in wood rather than concrete has reduced carbon emissions by an estimated 550 tonnes. For the purposes of comparison, one tonne equates to driving around 5,000 km in a car or flying between Stockholm and Rome. And the sustainability profile has proven attractive not only to the property market, but also to people looking to rent one of the new apartments.

“For the building’s launch, Slättö Förvaltning had hired a conference room for 200 people at the Steam Hotel opposite the site. But there was so much interest that not everyone got a seat,” recalls Ola Jonsson.

The sustainability approach also carries over into various features that the residents have at their disposal, including a greenhouse, an electric boat pool (like a car pool) and a bicycle workshop. The large glazed entrance serves as a meeting place and hub, with postboxes and even a fridge, where food deliveries can be left if the tenants are not at home. The sustainability profile, ingenious features, great location and publicity around this being Sweden’s tallest wooden building with a mass timber frame are probably just some of the reasons for the huge interest in the building. But those keen to live in the country’s tallest wooden building with a mass timber frame are unlikely to enjoy that status for long, as new and taller projects are already under way.

“While we look forward to seeing more, taller wooden buildings in the future, the important point is not the height, but the need for more buildings made of wood and for the construction industry to transition to a more sustainable way of building. Industrial wood technology is currently superior to other materials in this respect. We weren’t thinking about making it the tallest apartment block in wood when we were developing the plans, but it has had a great symbolic effect in showing just what is possible with wood at this moment in time,” concludes Ola.

Text Sara Bergqvist