Few materials can match the versatility of glulam. It is both stronger and stiffer than solid construction timber and it is one of the strongest construction materials in relation to its own weight. In addition, glulam encourages collaboration between architects and structural engineers, through the practically infinite freedom that it offers for design and implantation.

Sweden currently has three manufacturers of glulam – Moelven Töreboda, Martinson Group and Setra Wood Products. We begin with a trip to visit the centenarian – the world’s oldest glulam factory, attractively located in Töreboda, right on the Göta Canal between lakes Vänern and Vättern. Partly to chat with Johan Åhlén, CEO of Moelven Töreboda, and partly to dig into the company’s archive of pictures, documents and publications from years gone by.

“In terms of glulam manufacture, many things are similar to when the first glulam beams were made here in Töreboda in 1919. The technique is still based on joining high quality timber to make strong and durable beams. However, both the technologies and the production processes have changed over time. Often during ongoing production and in collaboration with customers,” says Johan Åhlén.

At Moelven Töreboda, development work at the historic glulam factory has followed two main tracks. One has been about finding structural solutions and building systems that meet specific requirements. The focus may be on improving acoustic and dynamic properties, such as reducing impact sound in apartment blocks or preventing swaying in tall buildings, which is a challenge when working with lightweight structures in wood.

The second track has been to develop the company’s own production processes, speeding them up, for example, while maintaining quality, preferably at a lower cost.

The centenarian we meet is certainly fit and healthy. Activity at the glulam factory has by no means slowed down. In fact, the place is as inquisitive, driven and forward-thinking as ever. Right now, they are involved in developing a wind turbine tower in wood together with the company Modvion. This is a patented technology, where a glulam structure allows both the weight and production costs to be kept down. The transport need is also being revolutionised, since the wood elements come in a kit of small pieces that are assembled into cylinders on site.

“We’ve spent two years working on the development of this project and we really hope it’s going to go well and become a feature of wind farms all over,” says Johan.

The start of the year saw the completion of the Mjøstårnet building in Brumunddal, Norway, which is currently the world’s tallest wooden building, at 18 storeys. This pilot project is mainly built around a glulam structural frame, and may well pave the way for other sustainable projects that explore new ways of using the material. The Frostaliden housing development in Skövde is another current project that, once completed, will be one of Sweden’s largest concentrations of wooden high-rises. Just like Mjøstårnet, the buildings have a wooden structural frame that uses Moelven’s proprietary post-and-beam system Trä8.

However, the history of glulam begins not in Töreboda, but in Germany in the early years of the 20th century.

In 1906, German joiner Otto Hetzer patented a method of bonding boards together to form curved structures. The aim was for the design of a load-bearing structure not to be restricted by the dimensions of a growing tree and by the capacity to manufacture different shapes and cross-sections. Another key element of the invention was to even out the effect of defects in the timber. Through sorting, the right grade of timber could be used for different parts of the cross-section, with better grades in the tension and compression zones of the structural element.

It was via forward-thinking Norwegian engineers and entrepreneurs that the glulam technology arrived in Sweden. Production first began at AB Träkonstruktioner in 1919 in Töreboda, where the factory building with Otto Hetzer’s three-piece arches, Sweden’s first glulam hall, still stands. Norwegian Guttorm Brekke purchased the patent for the Hetzer-Binder system, giving him exclusive rights in Sweden, Norway and Finland. He also gained access to the secret recipe for the glue that Otto Hetzer had developed.

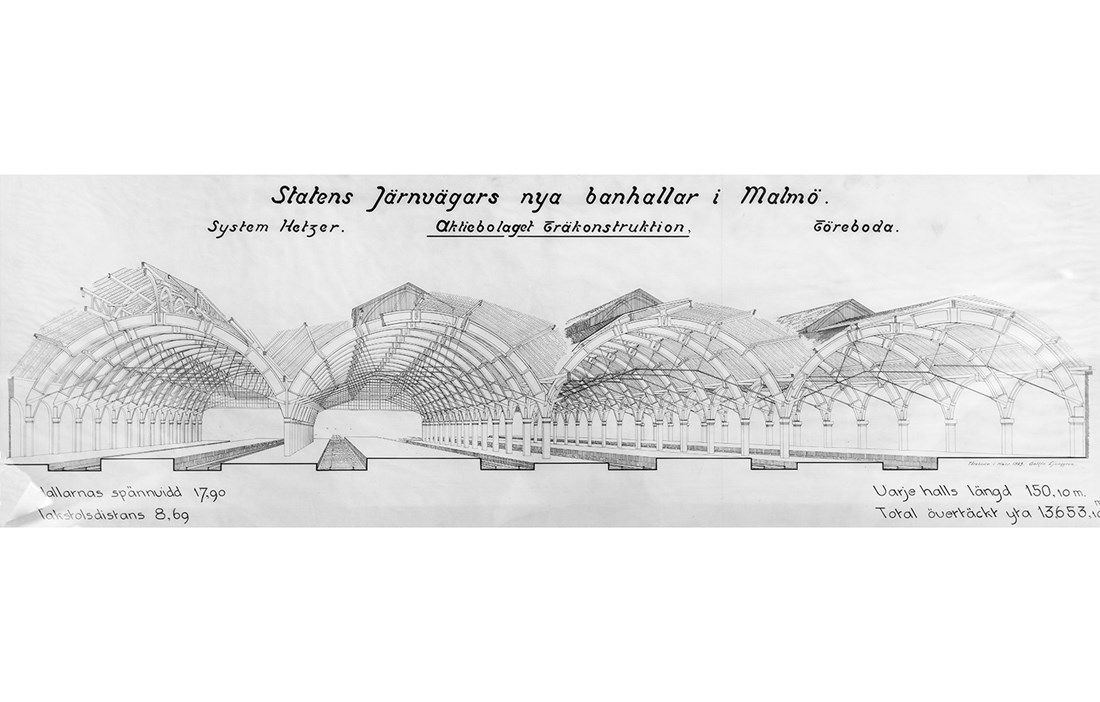

Around this time there was an extensive expansion of the rail network in Sweden, and AB Träkonstruktioner became an important supplier to the national rail company SJ, which in 1923 ordered glulam for Malmö Central Station’s train shed. The following year, AB Träkonstruktioner was declared bankrupt and the new company AB Fribärande Träkonstruktioner was formed. Their first order was for structural components for Stockholm Central Station, which proved an excellent start to the continued focus on roof structures in glulam.

Engineer David Tenning, who worked at AB Träkonstruktioner, played a key role in the development of glulam and became CEO of the newly formed company. Many spectacular buildings came about under his leadership, including the SALK-hallen sports hall in Alvik. Opened in 1937, it had eight glulam arches with a span of 47 metres. An aircraft hangar built at Västmanland Air Force Wing outside Västerås in 1937 had 10 glulam beams and a 55 metre span – the largest in the world at the time.

Sture Samuelsson is Professor Emeritus at KTH School of Architecture and the Built Environment in Stockholm and has been instrumental in developing modern wood construction in Sweden. He is also the author of Ingenjörens konst (The Engineer’s Art), a book about basic architectural history linked to materials and technical advances.

“Glulam is a fantastic material because it’s relatively light and can handle large spans. In Sweden, I’d pick out a couple of Carl Nyrén’s projects – the Mission church in Jönköping and Gottsunda church in Uppsala, both of which are incredibly stylish and wonderful examples of uncomplicated wood construction. I think we should focus more on developing applications and establishing the optimum degree of prefabrication for each project,” says Sture.

June saw the first parts go up for the frame of Sara Kulturhus, Skellefteå’s new arts centre. The 80 metre-tall building will rise to 20 storeys, which will make it the world’s tallest wooden building on its completion in summer 2021. The structural elements, around 10,000 square metres of CLT and 2200 cubic metres of glulam, are being produced at the Martinsons factory in Bygdsiljum outside Skellefteå and then transported to the construction site on the back of a lorry. The commission to deliver and assemble Skellefteå’s arts centre is the latest in a long line of major projects for Martinsons, which has considerable experience and has previously been behind a number of high-profile wood construction projects, in the form of schools, sports halls and housing all across Sweden.

Getting to deliver glulam for the world’s tallest wooden building, however, was not something the company’s founder Karl Martinson could have imagined when, in 1929, he purchased a mobile sawmill. Today, 90 years later, the company has developed a strong position with cutting-edge expertise in modern wood construction technology.

It was in the mid-1960s that Karl’s grandchild, the recently deceased Nils Martinson, headed off to Töreboda to find out how to run a glulam factory. He returned to Bygdsiljum fired up with enthusiasm and by 1965 the company’s glulam production line was up and running.

“Martinsons has always been innovative and brave and tried to find ways of adding value to wood, with glulam as a key component. In recent years, we’ve tried to simplify glulam as a product and make it easier and more accessible for builders’ merchants and end customers. This has meant promoting and raising the profile of the material, which has brought about a positive upswing,” explains Lars Källströmer, Sales Manager for building products at Martinsons.

Stig Axelsson is Sales Manager at Martinsons Byggsystem, which takes on turnkey contracts for the delivery and assembly of their frame systems in glulam and cross-laminated timber, plus their ready-to-assemble wooden bridges. He is seeing more and more people actively choosing a glulam frame, not least for environmental reasons.

“The developers have begun to wake up and understand that wood construction is a concept whose time has come. Now everyone wants the knowledge required to build in wood.”

In the 1960s, several players with varying levels of commitment entered the Swedish glulam market. The price dropped, as did the quality of the glulam beams, which failed to deliver what was promised. This prompted the serious glulam manufacturers to join forces in setting up a national institution for quality control, which was given the name Svensk Limträkontroll. A few years later, in 1973, Svenskt Limträ was formed as the Swedish glulam industry’s own body for technical information and development. Today this activity is organised by the Glulam Committee within Swedish Wood.

During the 1970s, hydraulics became increasingly common in the production of glulam. Stronger and larger machines with higher capacity were introduced, leading to the disappearance of many heavy, manual tasks. The glue used has also seen several stages of development, from the original casein glue to weather-resistant phenol-resorcinol glue. Today, melamine-urea-formaldehyde (MUF) adhesive is the main choice, producing a pale white glued joint. It is water-based and kinder to both people and the environment, and cures in seconds in a special microwave oven.

Holger Gross is a structural engineer who was head of Svenskt Limträ up until 2006. He is keen to shine a spotlight on the people behind the glulam – the production pioneers and those taking the tradition forward in such a brilliant way.

“There is huge commitment within the industry and an extremely high level of expertise at our three home-grown manufacturers. It is noticeable that the 100 years during which glulam has been available on the Swedish market have created an openness to the material. We still have some way to go when it comes to educating structural engineers and architects, but we’re getting there. The production of the Glulam Handbook Parts 1–4 and other investments in training material have certainly helped.”

The third glulam manufacturer, Setra Wood Products, is busy on one of the company’s largest glulam project so far. At its sawmill in Hasselfors, just outside Örebro, Setra is building a new industrial structure entirely out of glulam and CLT to house a new trimming and planing line.

Setra’s glulam production began in 1965 too, in the industrial town of Långshyttan in southern Dalarna. Initially, production ran alongside the sawmill, which also housed a roof truss factory. A new glulam factory was built a little over 30 years later, in 1996, and the factory then underwent an update worth around SEK 20 million in 2007. Since then, the production line has been adapted to meet increased customer demand for engineered wood and dimensionally stable products. For example, they have invested in a CNC machine in order to better meet requests for fully finished products.

The facility in Långshyttan has a high degree of automation and a production volume of around 50,000 cubic metres per year. The business is alive with a spirit of innovation, and employees have worked on every little detail to optimise working practices for improved efficiency.

“We’re noticing a growing awareness about glulam, with the material capturing market share for building frames. This is because it’s strong, attractive and easy to handle and work with. In addition, it has an obvious place in an ecocycle society. The work that has been done in Långshyttan is admirable in so many ways. There is an incredible forward momentum, with all the staff aware that their efforts are crucial to the end result,” says Thomas Kling, glulam product specialist at Setra.

In recent years, Setra has streamlined its business and focused on the building and construction segment, which includes glulam. Over the summer, the company launched a new concept for standard halls with a glulam frame, particularly tailored to operations in agriculture, manufacturing, warehousing and logistics.

Technical advances in the industry have helped to raise the quality of Swedish glulam products. The sawmills have constantly raised the bar, for example with improved sorting equipment. This means the material supplied to the glulam manufacturers is of a consistently high quality. Combining digital technology with mechanical processing has revolutionised the industry in many ways. Computer numerical control (CNC) machines allow the beams to be processed automatically and tolerances are reducing, so large structures can be designed with many different components that are connected together with millimetre precision.

At KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, we meet Roberto Crocetti. He has a wealth of experience in wood construction, both as an engineer and former head of research and development at Moelven Töreboda, and as a researcher and lecturer at Chalmers University of Technology and Lund University. He has been a visiting professor at KTH since autumn 2017 and in autumn 2018 he made his return to Töreboda.

“So many students have a deep interest in wood. They can see the environmental advantages and are surprised when I show them what can actually be achieved.”

We end where we began, with the vigorous centenarian in Töreboda. In Sweden’s first glulam hall, Roberto Crocetti has built a test rig to try out advanced connections, floor solutions and beam designs. He is buzzing with ideas about how glulam can be developed and is open to combinations with other materials.

“I think we should be using as much wood as possible, but not to an absurd extreme. You then risk jeopardising both function and aesthetics. My students and I are looking at developing new connections that would make glulam more competitive, as well as the possibility of using woods other than spruce to improve both strength and durability. If you have even the least bit of interest in the art of engineering and design, wood is a fantastic material, particularly in the form of glulam.”

Although much has remained the same since the country’s first glulam beam was manufactured a hundred years ago, new technology, new production processes and new knowledge are helping to constantly improve the scope for self-expression through the material.

Text Katarina Brandt