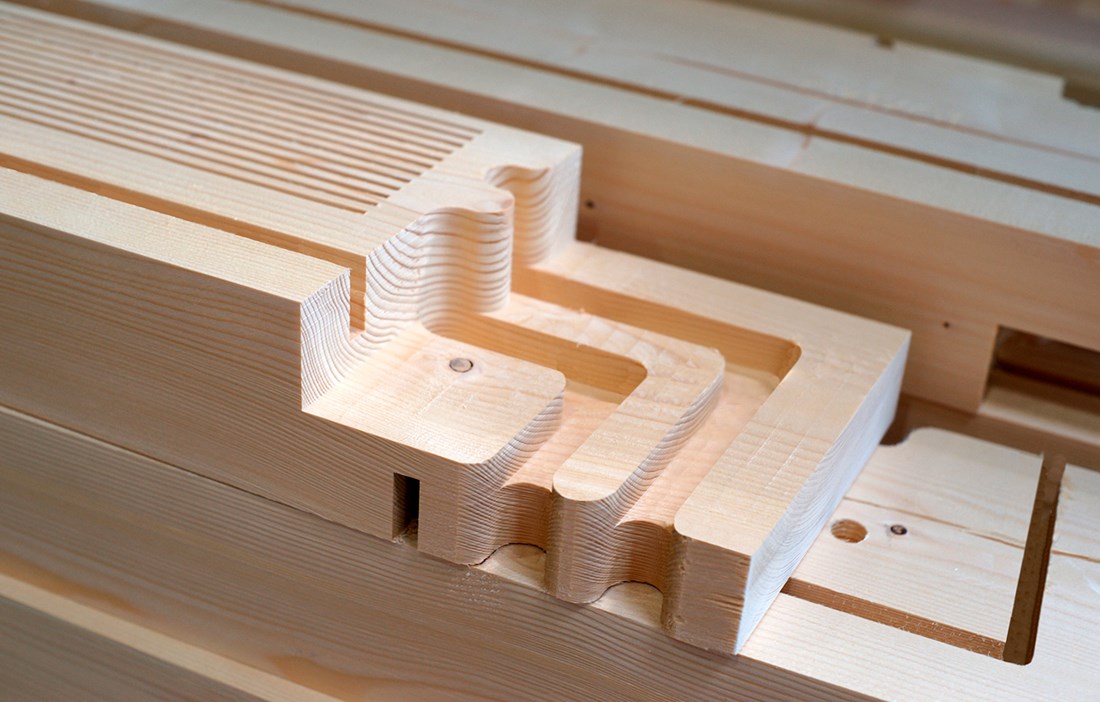

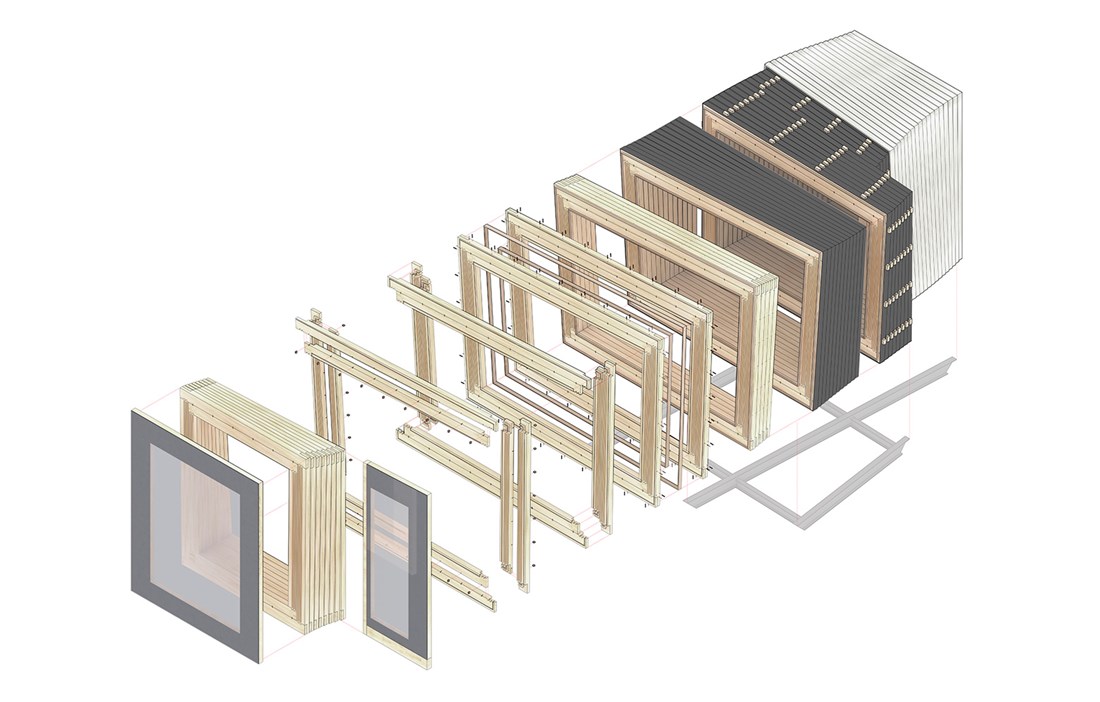

The international building exhibition IBA Thüringen in Germany offers an insight into what smart wood construction of the future might look like. In terms of the exterior, the prototype house shown here has drawn a great deal of inspiration from traditional German log cabins. A key difference, however, is that the timber has been placed vertically instead of horizontally, and that the design is based on a series of upright frames in solid wood. These in turn are connected using airtight wooden joints. This system of digitally programmed and CNC milled nodes with exact precision creates an extremely strong structure without any need for metal plates or glue.

“This is one of the building’s many advantages in terms of sustainability, because it makes it easy to disassemble and recycle the whole thing at a later stage,” explains Oliver Bucklin, research assistant at the University of Stuttgart, who headed up the design and development of the prototype house.

The project, which has been running for almost two years, has involved close collaboration between the University of Stuttgart, the University of Oldenburg, IBA Thüringen and partners from the business world. The ultimate aim is to be able to industrialise the building process and begin mass production of the house.

“We still have a few tests and steps to complete, for example to do with airtightness and insulation values. But in 5 to 10 years, it’s fully possible that holiday homes based on this prototype could be a reality. And the principle could also be used for larger buildings,” says Oliver.

Although the inspiration for the house is based on old joinery traditions, the design brings everything bang up to date. The front façade comprises a framed expanse of glass that creates wonderful views. Internally, wood elements have a soft, arch-shaped momentum that creates a warm and vibrant feel.

Absolutely everything in the house – from the structure to the envelope, insulation and connections – is made of wood. Sawing slits into the solid, vertical wood units helps to even out tensile forces and deliver good insulation values that meet the German requirement for a U-value of 0.20.

“The slits reduce the wood’s inclination to split and even out the variations that built up as the tree grew and was subjected to natural forces in different directions. They also form effective air pockets that help to increase the house’s insulation values,” says Oliver.

The façade has been fitted with a flexible membrane that makes the building watertight on the outside, while also being breathable to let out interior moisture. The energy values are so good that the house can be used all year round, despite the severe winters locally which can see temperatures plummet to -15°C. The building is currently heated by a single radiator, but Oliver Bucklin sees passive solar heating as a potential future alternative.

“Wood is also an excellent material for achieving a good indoor climate. One of woods lesser-known properties is its capacity to absorb infra-red light, which makes it a much warmer and more pleasant material than steel and concrete, for example.”

In its current form, the building comprises 58 wood frames, each made up of 8 wood elements, totalling 464 components, plus 2 window frames. One of the biggest challenges lay in adapting the size of the various elements, both for the purposes of sawing and milling, and when it came to transporting the pre-assembled frames. The largest module that had to be transported was composed of 12 frames and measured 3.2 x 5.0 x 1.2 metres.

“One alternative in the future could be for us to create a portable production system that means the house could be assembled on site, says Oliver Bucklin.

Text Sara Bergqvist