During the autumn, the first tenants have moved into A Working Lab at Johanneberg Science Park, on the Chalmers campus in Gothenburg. This is Akademiska Hus’s first building with its own innovation programme for both the construction process and the finished innovation centre. Behind the red glass façade sits an exciting, experimental environment that is intended to serve as an arena for and physical link between academia, business and society.

Construction of the 11,700 square metre premises began in May 2017. As the office block emerged, 16 innovation projects were carried out, using the building itself as a testbed. These projects focused on everything from smart energy solutions and new ways of building in wood to the form that future outdoor offices and learning environments might take.

“The fact that the building has been an important place for innovation throughout its construction has made this a fantastic project to manage. It’s exciting to see how much innovative energy is poured into a successful collaborative project like this,” says Jan Henningsson, project manager for Akademiska Hus.

The idea from the start was to use the right materials in the right place in order to reduce the carbon footprint and secure the building’s long-term sustainability. The block has therefore been built with a hybrid frame (a load-bearing structure comprising more than one material), with the basement level and the stabilising lift shaft made from concrete, while the floor structure is CLT, the posts are glulam and the beams are steel. The hybrid frame made it possible to optimise the number of floors with regard to the current detailed development plan. The advantage of the hybrid frame on this project was that it kept the height of each level down, allowing for an additional floor in compliance with building regulations.

“The frame can best be described as a traditional prefabricated concrete frame with steel posts, T-beams and hollowcore flooring. The difference is that the floor components and the majority of the posts have been switched to wood,” explains Per Hilmersson of Integra Engineering, who has been the chief structural engineer on the project.

Designing a sustainable property was a key factor both for Akademiska Hus and for Tengbom in Gothenburg, the firm responsible for the building’s exciting and innovative architecture. Supervising architect Susanne Kovacs Österberg and lead architect Kerstin Sandholt agree that the collaboration between the various parties has been both open and inclusive.

“It is fairly uncommon as an architect to work as closely with the client as we have done on this project. We’ve received support on the architectural ambition, vision and budget and been able to monitor, steer and keep the architectural objective clear for everyone involved. This has led to unusually good teamwork and a smooth process, which in turn has had a positive impact on the end result,” says Kerstin Sandholt.

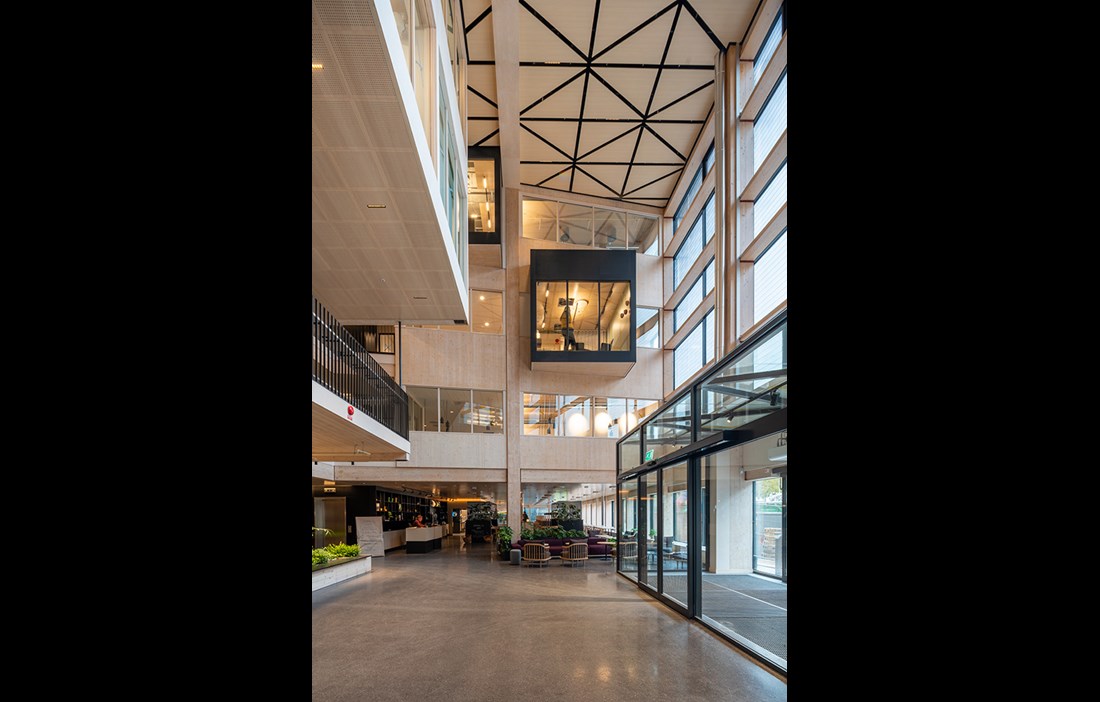

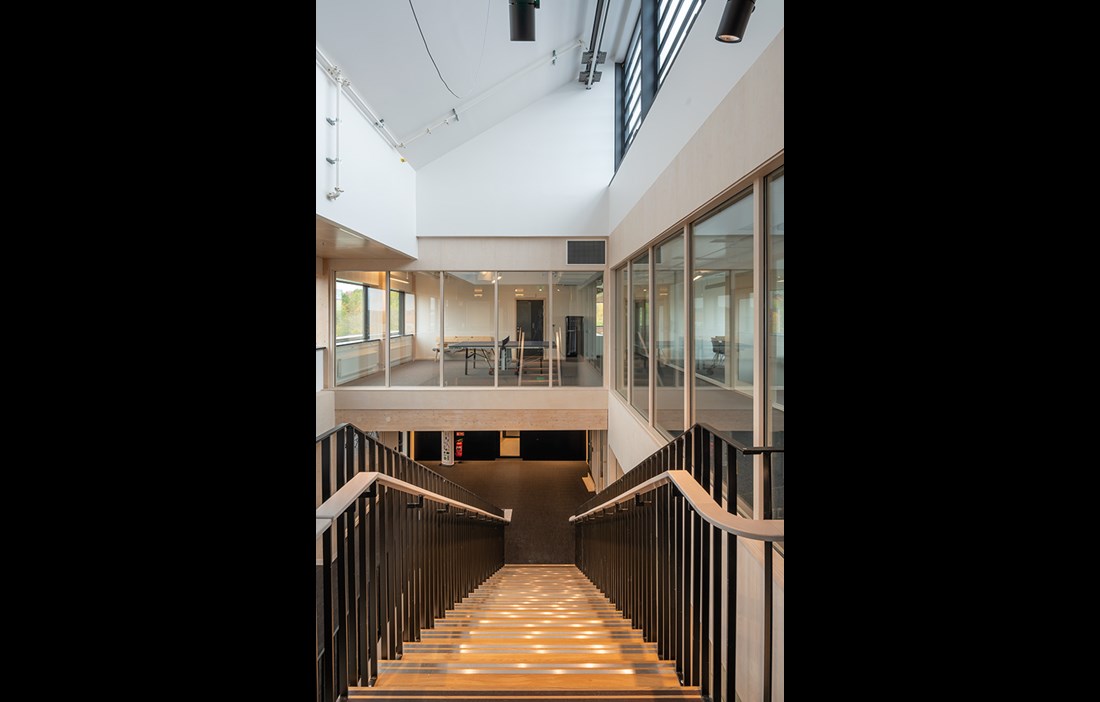

A Working Lab is at once a public and a private building, where the flow through the open entrance level invites innovative clashes between different skills and backgrounds. It is a lively space with a café, restaurant, meeting places and workspaces. Level 2 has a co-working area that people from outside can use for a fee. The five other floors are offices for tenants including Akademiska Hus itself and the national research institute RISE.

“Our aim has been to put as much exposed wood on display as possible. The material has a calming effect on people and a number of scientific studies have shown that it promotes health. Wood has been a natural feature in the design of the collaborative spaces, where the wooden structure helps to create a warm and inclusive environment,” says Susanne Kovacs Österberg.

To retain the warm wooden feel, the installations are visible or encased in wood wool cement board, which was chosen for its materiality, but also because it has a good environmental profile. The interior of the entrance hall is complemented with birch plywood on the walls and ceiling. The stairwells are lined with coloured MDF panels for indoor use.

Building in wood comes with challenges relating to damp and acoustics, for example. One of the innovation projects initiated by Akademiska Hus has therefore investigated what happens if you build in CLT without using a tent for weather protection.

The reason why a tent could not be used was that the plot was squeezed between other buildings. The project began by studying how well the cross-laminated timber stood up to moisture. The tests were performed by placing pieces of the wooden floor structure on the roof of the site offices. The pieces were left there for three months, exposed to all kinds of weather. Sensors continually measured the moisture content to see what effect moisture was having. The results showed that moisture did not penetrate as deeply into the wood as previously thought.

Building with an uncovered floor structure meant that construction work had to be fast so as not to expose the wood to moisture for longer than necessary. Various detailed solutions were planned during the build, including protecting all the end wood, which is particularly sensitive to moisture, taping the joints between the wooden blocks and constantly measuring and monitoring moisture content. Once the walls were in place, the window openings were sealed and the building dehumidifier was installed to speed up the drying process. The results of the project will now be turned into a report for use on similar construction projects in the future.

Another innovation project involved experimenting with different solutions to optimise the acoustics in the building. In a lab environment, tests were carried out to see how sound travels through wooden floor structures and a range of solutions using insulation, plasterboard or floor screed.

“Sound and vibrations behave differently in a wooden building compared with a concrete building, for example. To ensure a good indoor environment, it’s important to raise these issues early in the construction phase. With the large quantity of measurements we’ve taken, we can provide the industry with a great deal of knowledge about wood construction,” says Per Hilmersson, who was responsible for the project.

And the measurements continued during the build. In fact, they are still continuing now that the building has been furnished and completed, adding to the bank of knowledge on acoustics in large wooden structures – from planning to finished building. The results will be useful for other construction projects, generating knowledge that has not previously been collated and made available.

“It has also been exciting to look at different solutions to bring down carbon emissions in the construction phase. A climate calculation of the construction project’s carbon footprint shows a considerable reduction due to the choice of materials. Just by mainly choosing a wooden structure, we managed to reduce the building’s climate impact by up to 20 percent,” says Peter Karlsson, head of innovation at Akademiska Hus.

The joint work on sustainable construction has paid off, with A Working Lab achieving the Miljöbyggnad eco-certification scheme’s top level, Gold, in September.

text Katarina Brandt