When the Rudolf Steiner School in Geneva was built in 1988, on land donated to the school, it was way out in the countryside. Recent years have seen development creep ever closer, and today the school is surrounded by the expanding city, with a tram stop right outside the entrance.

The Rudolf Steiner School has constantly grown since the beginning and now has around 350 students. The expansion of the preschool provision also made the need for additional space even more pressing. The school therefore decided to build an extra floor on top of the original concrete structure.

“We had no other choice but to build upwards. For one thing, we had no spare land, and we also had local planning rules to contend with,” explains Jérôme Hayoz, a member of the working group of parents and teachers that provided the link between the school and the architect.

The architect of the original building, Jean-Jacques Tschumi, had in fact planned for another floor when the school was built almost 30 years ago. It was never realised back then, but finally its time had come. The challenge then was to produce a concept for the extension that teachers and parents at the school could accept.

The challenge was taken on by architectural practice Localarchitecture. They were familiar with the renowned architecture that comes out of the symbol-laden anthroposophical design principles, since a few years earlier they had designed a Steiner school in Lausanne.

“Our ambition in Geneva was to create a whole building that concluded what architect Jean-Jacques Tschumi had begun,” explains Antoine Robert-Grandpierre, architect and partner at Localarchitecture.

But instead of building on Tschumi’s project, with an extension that spoke the same language, they opted for an airy and light design, a kind of stunning penthouse, where the gaze is drawn to the sky and the open landscape rather than the heavy concrete of the existing school building.

“From the outside, the extension looks like it has always been there, but inside, from the stairs that have been extended up to the new level, you get a feeling of stepping into a whole new world,” says Antoine.

The reason for building the extension in wood was mainly to minimise the load on the existing structure. However, the fact that the material is easy to work with and prefabricate also came into play, and the school was keen for an ecological, sustainable and attractive material to be used.

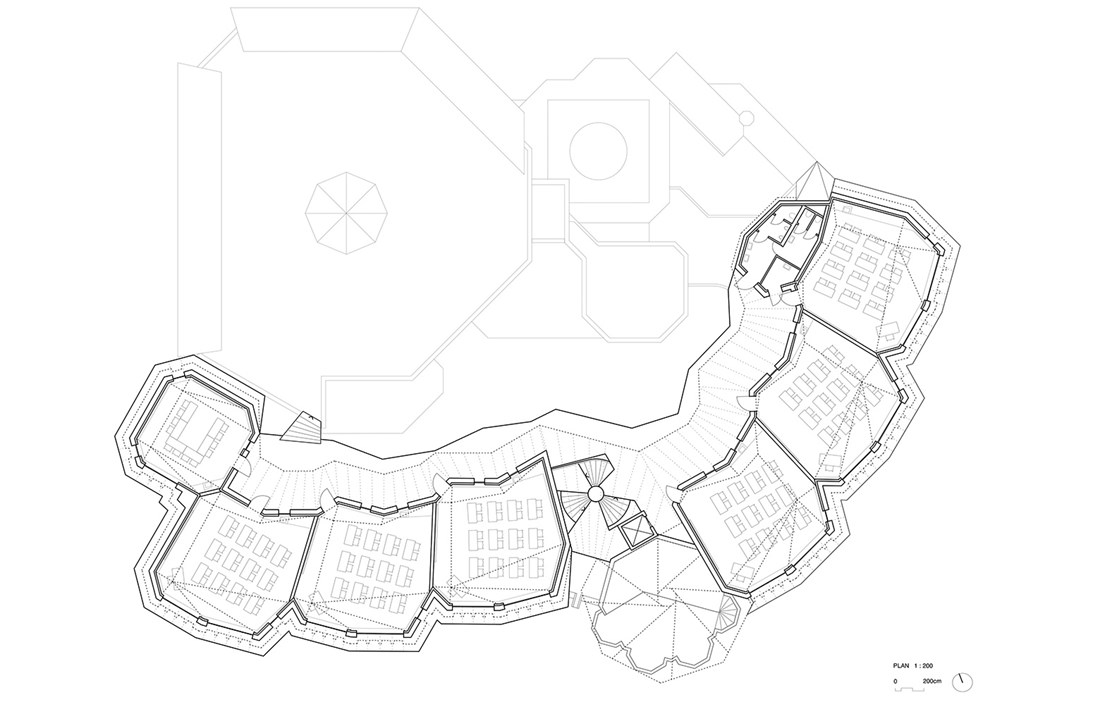

The client also wanted the school to remain open for the majority of the construction time. Localarchitecture therefore proposed a solution that avoided noise, dust and heavy lifting by building the nine-sided classrooms off-site in wood and then lifting them into place and assembling them during the school holidays.

“We’ve used wood in all the structural elements, with the exception of the access balcony, where we chose to make use of the reinforced concrete that had already been laid in the floor,” comments Antoine.

Since Jean-Jacques Tschumi and his structural engineer had an idea that a penthouse level would crown the building, concrete posts and beams were already prepared in the original school building.

The new level is therefore built entirely on the existing structure, with new walls in wood positioned directly above the blockwork walls on the floor below, and has been anchored into place with stainless steel bolts, four centimetres in diameter and spaced two metres apart.

To make space for insulation on the slightly angled roof, the level of the access balcony was raised by around 30 centimetres. Existing posts and beams have been used, supplemented by new ones in wood.

“This creates a clear boundary, where old and new meet,” says Antoine Robert-Grandpierre.

The new classrooms have CLT walls (12 cm) and ceilings (8 cm). Glulam is used for the roof beams and window surrounds. Internally, the whole of the load-bearing structure in knotty spruce is exposed, with the walls insulated on the outside and lined with larch cladding.

Antoine stresses that designing and constructing the nine-sided classrooms so they could be lifted into place and joined to each other on top of the old school would have been almost impossible using traditional 2D technology. This project also had a complex workflow and major geometric challenges, with a ‘topographical’ roof where many angles and several large windows had to be visualised.

“This was therefore one of the very few projects where we used 3D technology from the very start. In so doing, we created a tool that could also communicate with structural engineers and carpenters and, ultimately, with the CNC machine that cut the wood,” says Antoine Robert-Grandpierre.

In the next breath, he points out that the project involved more than just the addition of an extra floor with seven nine-sided classrooms. Another element of the project was a new, attractively decorated, entrance in glass and wood that connects the different parts of the school, plus an atmospheric atrium leading to the winding staircase that takes visitors and students into and up through the building. New life has thus been breathed into several parts of the Rudolf Steiner School.

“I’d say it has lit a fresh spark,” he says.

Another aspect of the school project that he chooses to highlight is the close collaboration that the architects and structural engineers have had with teacher and parent representatives from start to finish.

To avoid the project descending into chaos at the self-governing Rudolf Steiner School, with complex planning and many different voices and views, the small working group that was formed provided an important channel for information in both directions.

“But most importantly of all, the real clients – the students at the school – were included in the whole process, with regular discussions and study visits,” concludes Antoine Robert-Grandpierre.

text Mats Wigardt