In recent years, much of Norwegian wood construction has been about coming first, being the biggest and soaring highest into the sky. This trend is represented by buildings such as Treet in Bergen, which for a short while was the world’s tallest wooden building, and Mjøstårnet in Brumunddal, which at 85.4 metres is the current record holder. Now Finansparken in Stavanger, which opened in November 2019, has taken the crown as Europe’s largest office building in wood.

The executives of Sparebank 1 SR-Bank had long been considering gathering their operations under one roof when they announced an architectural competition for their new headquarters in 2013. In the competition brief, the bank expressed a desire for a building with high architectural and functional qualities, extensive flexibility, good operating costs and innovative solutions concerning the spatial layout and work environment. In short, a signature building that the bank and its employees could be proud of. The entry that went on to beat the 17 other candidates came from local architectural practice Helen & Hard, in partnership with Oslo-based SAAHA.

However, there was no guarantee that the bank’s new headquarters would be built in wood. To convince their client, the architects took the bank’s management team on a tour of Germany, Austria and Switzerland to see some exemplary designs. Media group Tamedia’s head office in Zürich, designed by Shigeru Ban, was one of many inspiring eye-openers. It also served as a 1:1 scale model demonstrating the tactile benefits of wood and the inherent potential of designing and building in wood.

“Wood is a good environmental choice that feels modern and forward-looking, providing a good match with the bank’s values. We also wanted our new headquarters to blend in with Stavanger’s existing wooden buildings. What’s more, wood helps to create a warm, functional and pleasant environment where our customers and employees can meet and spend time,” comments Arne Austreid, CEO of Sparebank 1 SR-Bank.

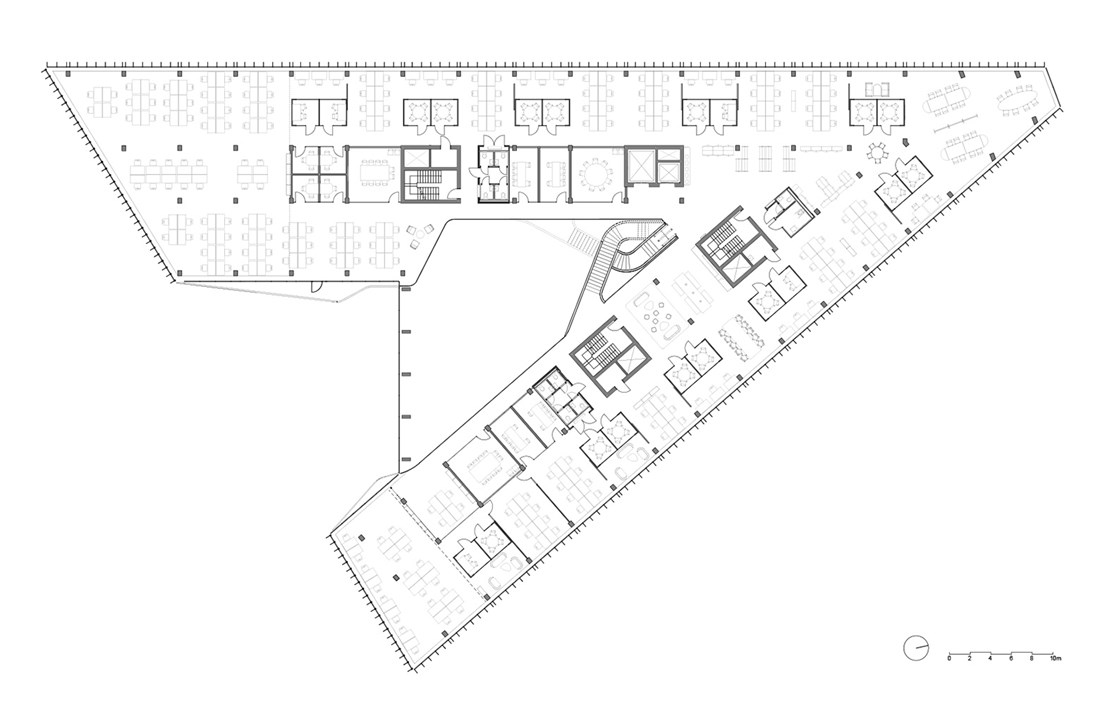

Finansparken is wedged into an almost triangular plot in the Bjergsted district, just north of central Stavanger. The plot formerly served as a car park and sits adjacent to the city’s traditional timber-framed residences. The wedge shape, both horizontally and vertically, has created a building that changes character and scale in its interaction with the surrounding cityscape. Helen & Hard entered into partnership with SAAHA, and the main concept was developed in close collaboration during the competition and preliminary planning phase. The division between façade (SAAHA) and interior (Helen & Hard) was only decided in the detailed development phase.

“The architecture is based around the contrasts between a sharply defined exterior and a softer, more organic interior. The result is far from discreet, yet it still merges in with the existing buildings,” says Njål Undheim, senior architect at Helen & Hard.

The building sits on a load-bearing structure made of both site-cast and prefabricated concrete. The space below ground comprises three levels that house a parking garage for 200 cars and various utilities. Concrete has also been used in the three centrally located stairwells and in the lift shaft, which helps to stabilise the building.

The complex wooden structure is precision crafted by Creation Hols and Hermann Blumer. It comprises a framework of prefabricated beams and posts in glulam, reinforced with LVL beams in beech veneer that were pre-assembled and then erected on site in Stavanger. Instead of steel fixings, the choice went to a special connection system using 80 millimetre-thick wooden plugs in beech hardwood. The design involves 3,500 beech plugs in total. CLT has been used in the floor system to stabilise the building through diaphragm action. Assembly was completed in sections rising vertically, with each section quickly fitted onto the next.

“One of the biggest challenges was to keep moisture at bay without weather protection in one of Norway’s rainiest cities. All the glulam was therefore delivered and assembled in plastic wrap,” relates Thor Olav Solbjør, architect and CEO of SAAHA.

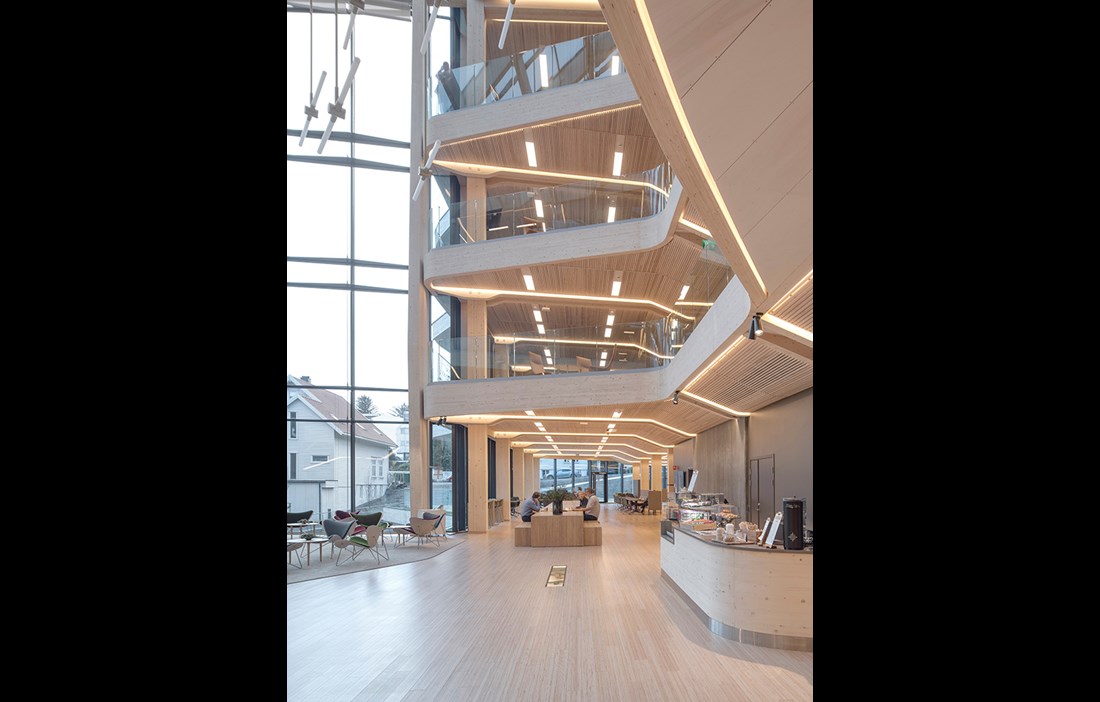

The entrance level has a double roof height, with fewer posts in order to create a sense of space. The posts and beams used in the first three floors are made of laminated veneer lumber (LVL) in the form of “Baubuche” from German company Pollmeier. They mainly delivered 40 millimetre beech veneer panels to Moelven Limtre, which glued and finished the material. Knot-free veneer has been used for the top layer on all exposed surfaces. The fact that beech is heavier and stronger gives the material high tensile, compression and bending strength, which enables more slender designs than would be possible with traditional spruce glulam. The ability to choose an extra high surface finish also makes Baubuche a good option for exposed structural elements.

The other floors use locally produced glulam, finished by Moelven Limtre. The deliveries to Finansparken are by far the company’s biggest since Gardermoen Airport was built in Oslo in 1998. CNC processing of the elements employed two full shifts over the course of a year. In all, the factory in Moelv delivered 1,900 cubic metres of CLT, 1,100 cubic metres of glulam and 600 cubic metres of beech LVL. The exposed wooden surfaces were polished by hand in the factory to achieve the best possible finish.

“The walls and ceilings are connected using 67,000 screws, based on 750 assembly drawings. The design required extremely high standards for the prefabricated glulam elements, and the holes were made with a precision of a tenth of a millimetre,” explains Moelven’s project developer and senior consultant Åge Holmestad.

The southern and lowest part of the Finansparken development faces towards the city’s old timber-framed residences, which are only a stone’s throw away. From here, the building rises northwards up to a height of seven storeys. Crowning everything are the bank’s reception rooms, with stunning views of the fjord and the surrounding mountains.

“Our watchwords have been transparency and openness. By giving Finansparken a fully glazed façade, we open the building up to the outside world,” says Thor Olav Solbjør.

This transparency is accentuated through passive solar screening in the form of 2 centimetre-thick vertical glass fins. These bring life to the façade and provide a look that changes with the weather. The fins are made from one clear and one bronze-coloured layer sandwiching a laminate coated with a solar film. In total, 5 kilometres of these glass fins have been used for the façades.

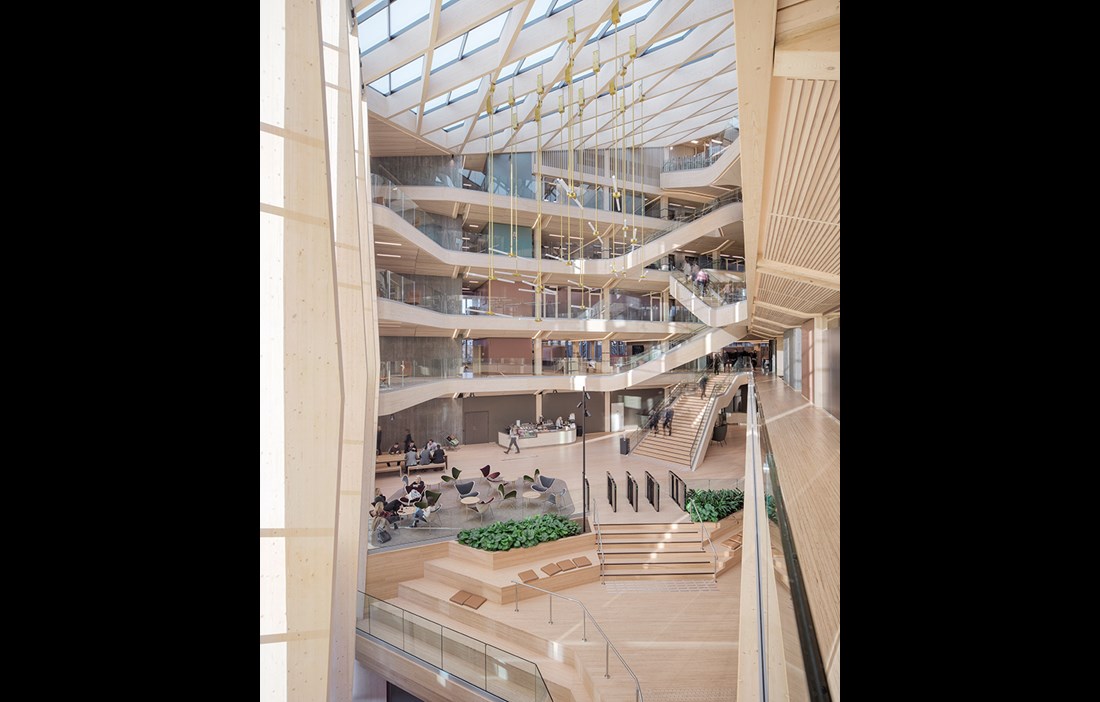

The atrium that greets employees and visitors to the left of the main entrance forms the heart of the building, with all the social zones facing towards it. What this creates is a warm, open space that draws in daylight via a fully glazed façade and a glass ceiling resting on a diagonal grid of glulam. The glass is made by OKALUX, and despite its high solar protection factor, it lets in a soft and attractive light that prevents sharp shadows in strong sunlight. The artwork Flocking lights over epic waters by Joachim Sauter also hangs in the atrium. It comprises a cylinder-shaped light fitting that communicates digitally with buoys out in Byfjorden and moves in time with the movement of the waves.

There is plenty to capture the eye in Finansparken, but perhaps the most striking feature is the sculptural staircase that punctuates the open atrium in the main entrance and winds on up through the building. The double-curved glulam beams were made by Hess Timber in Frankfurt, one of only a few companies capable of mastering the complex geometry.

Despite the project’s complexity, everyone involved bears witness to an excellent collaboration. Njål Undheim puts this down to a number of contributory factors: a client that has been clear about what they wanted to achieve, professional project management, skilled subcontractors and the fact that Finansparken is a reference project with which everyone has been proud to be involved.

Sparebank 1 SR-Bank moved into its new offices on 29 November last year, 180 years to the day after they were granted a banking licence with start-up capital of 224 Norwegian crowns, or 56 specialdalers as it would have been back then. Now the bank is looking to a future in which the new headquarters will serve as a value-creating centre of expertise for both customers and employees.

“Since the bank was founded in Egersund 180 years ago, we’ve never had a proper head office. Now we have a signature building that we expect to last for at least that number of years,” concludes Arne Austreid.

text Katarina Brandt