Properties of softwood

Wood is the construction material with the oldest heritage in Sweden. Since wood is used for a whole host of purposes in construction – structural frames, exterior and interior wall cladding, fittings, floor coverings, formwork and scaffolding, the list goes on – it is important to understand how wood behaves under different conditions. Due to their own specific properties, each type of wood has typical areas of use.

Spruce is the wood used primarily as construction timber. Pine is commonly used for joinery, mouldings and internal cladding, although spruce may be used. Hardwoods such as oak and beech are used in flooring and furniture.

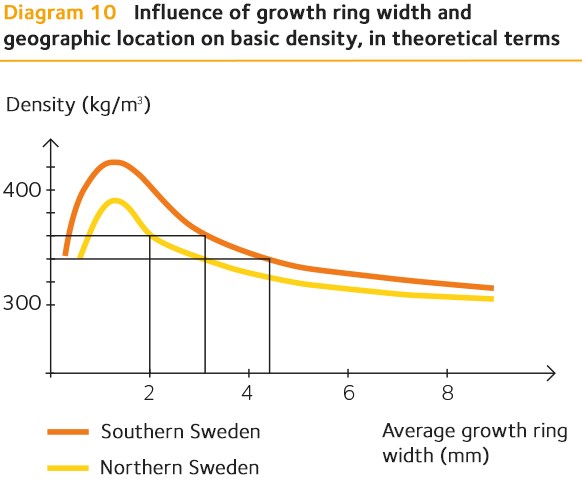

Wood from southern Sweden is denser, stronger and more durable than wood from northern Sweden. This is despite the fact that southern Swedish wood generally has broader growth rings than wood from northern Sweden. The reason for this is that the summerwood band, the dark part of the growth ring, is wider in southern Sweden. Summerwood, which weighs 900 kilos per cubic metre dry wood, is three times denser than springwood, which weighs 300 kilos per cubic metre dry wood.

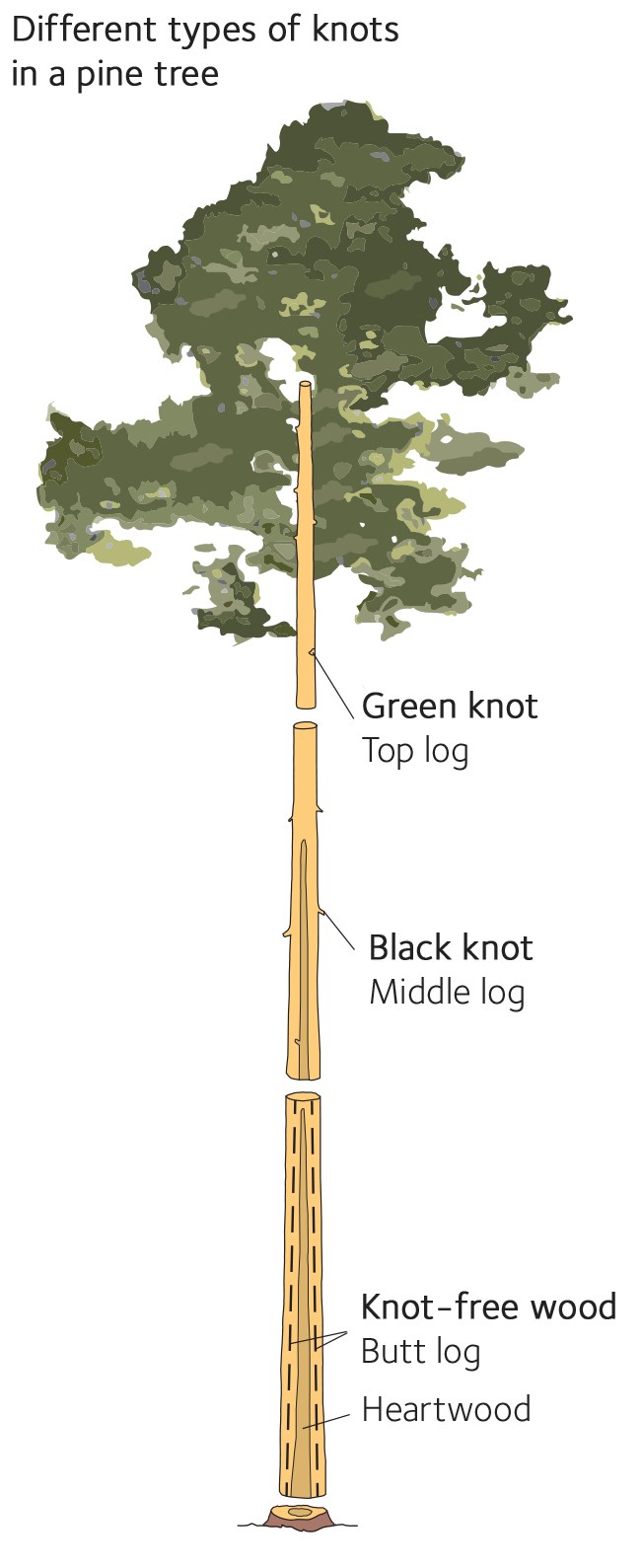

Material properties vary between the different wood species. Even within the same wood species, there are major variations between different locations, but also between different trees grown in the same location. There is, however, even greater variation within a single tree, for example between different heights in the tree, between wood that is close to the pith and to the bark, and between springwood and summerwood in the individual growth rings. Knots and other fibre distortions (imperfections) also affect the wood’s technical properties.

Normal variations for the properties of density, strength and stiffness (modulus of elasticity) within the same wood type with an undistorted fibre structure:

- Density ±20 percent

- Durability ±40 percent

- Modulus of elasticity ±35 percent.

The quotient is therefore greater between, for example, the average material strength of wood and allowable working stress, in comparison with other construction materials.

Tabel 11 Technical data for pine and spruce

The values for strength and modulus of elasticity are average values, and refer to small test samples, with no imperfections, at an average temperature of 20°C.

The figures with no brackets state properties parallel to the fibres (II) and the figures in brackets state properties perpendicular to the fibres (T).

All the values relate to wood with 12% moisture content.

In spite of the differences between pine and spruce, they should be considered statistically equal in construction terms.

| Property | Pine | Spruce | |

| Moisture content (%) | II | 12 | 12 |

| Basic density (kg/m3) | II | 420 | 380 |

| Density (kg/m3) | II | 470 | 440 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | II | 104 | 90 |

| ḻ | (3) | (2,5) | |

| Bending strength (MPa) | II | 87 | 75 |

| Bending strength (MPa) | II | 46 | 40 |

| ḻ | (7,5) | (6) | |

| Shear strength(MPa) | II | 10 | 9 |

| Impact strength (KJ/m2) | II | 70 | 50 |

| Hardness(Brinell) | II | 4 | 3,2 |

| ḻ | (1,9) | (1,2) | |

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | II | 12 000 | 11 000 |

| ḻ | (460) | (550) | |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m ̊ C) | II | 0,26 | 0,24 |

| ḻ | (0,12) | (0,11) | |

| Heat capacity (J/kg ̊ C) | II | 1 650 | 1 650 |

| Calorific value (MJ/kg) | II | 16,9 | 16,9 |

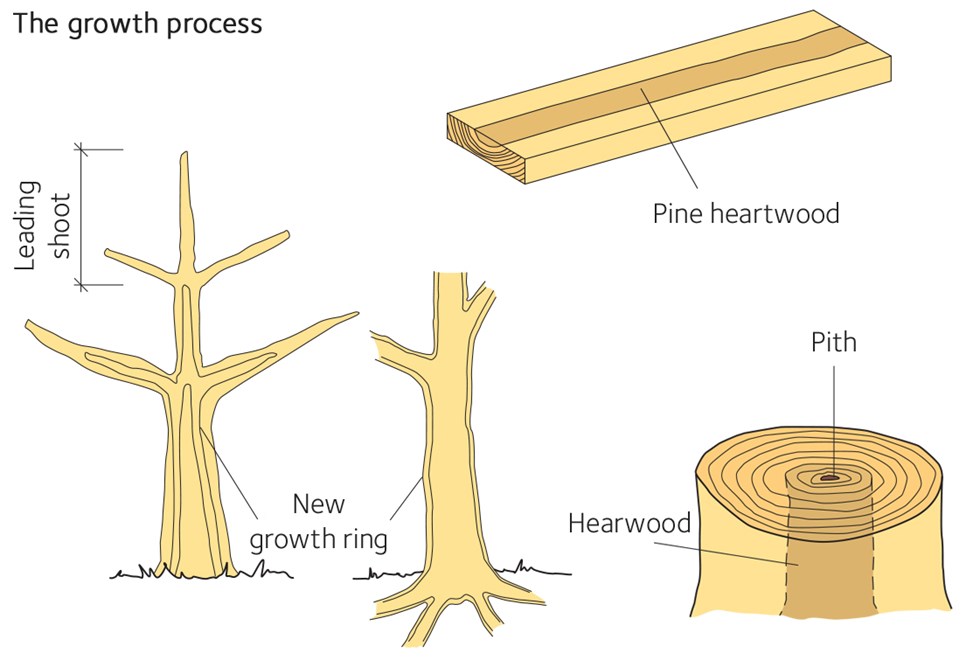

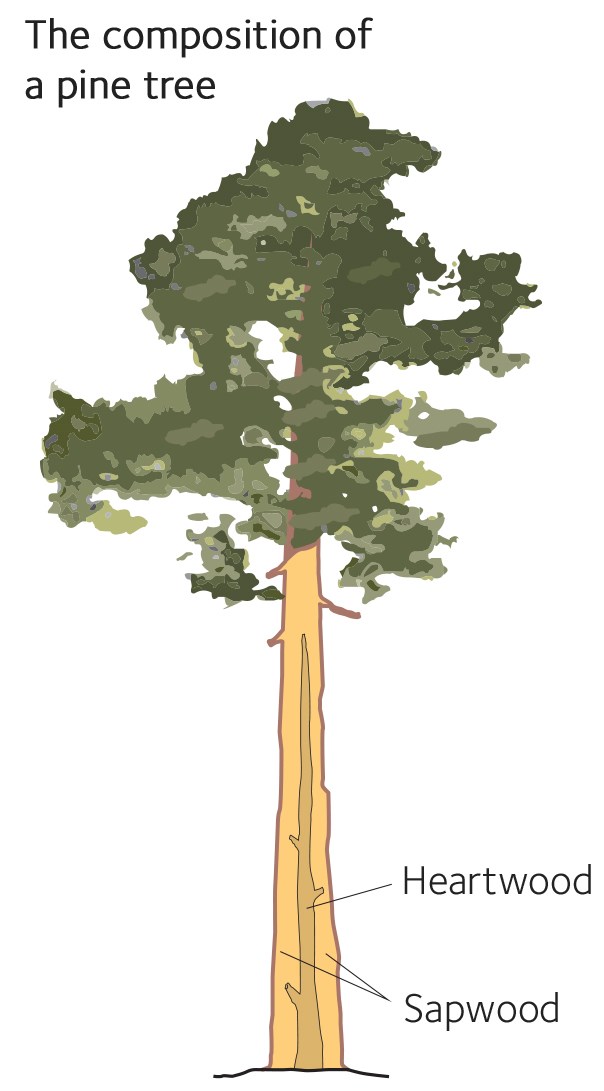

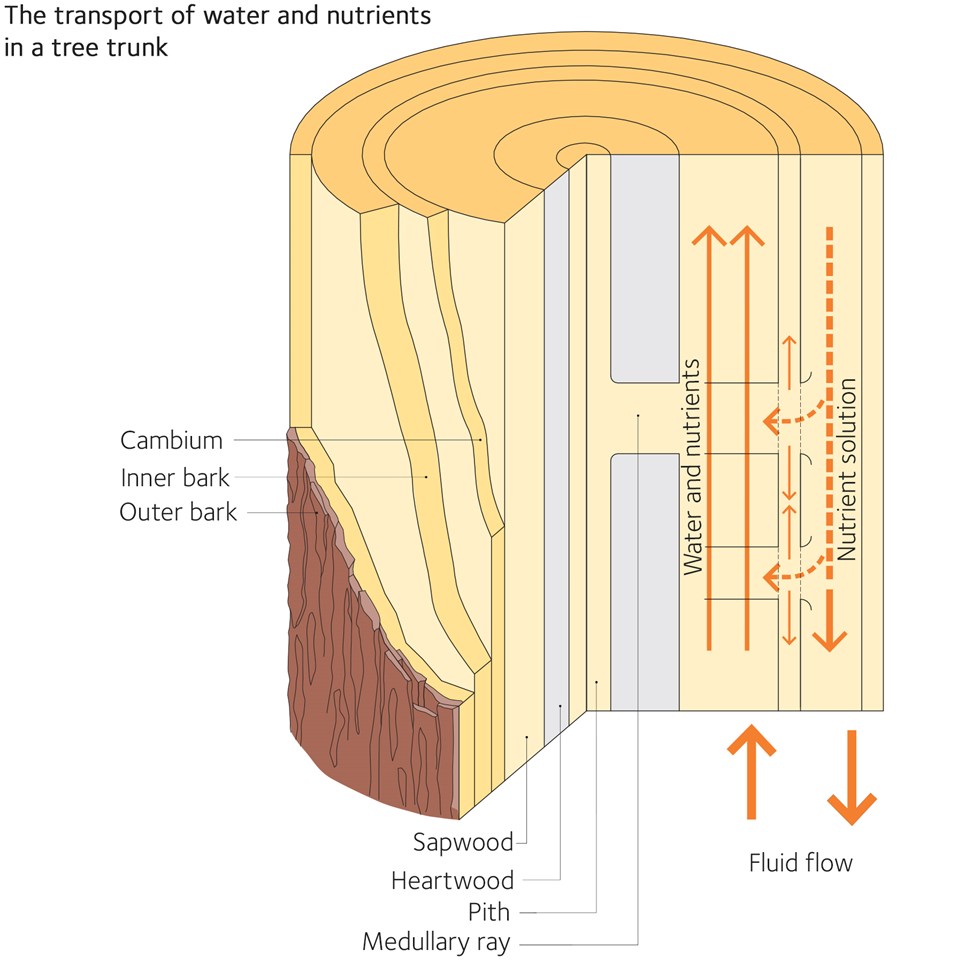

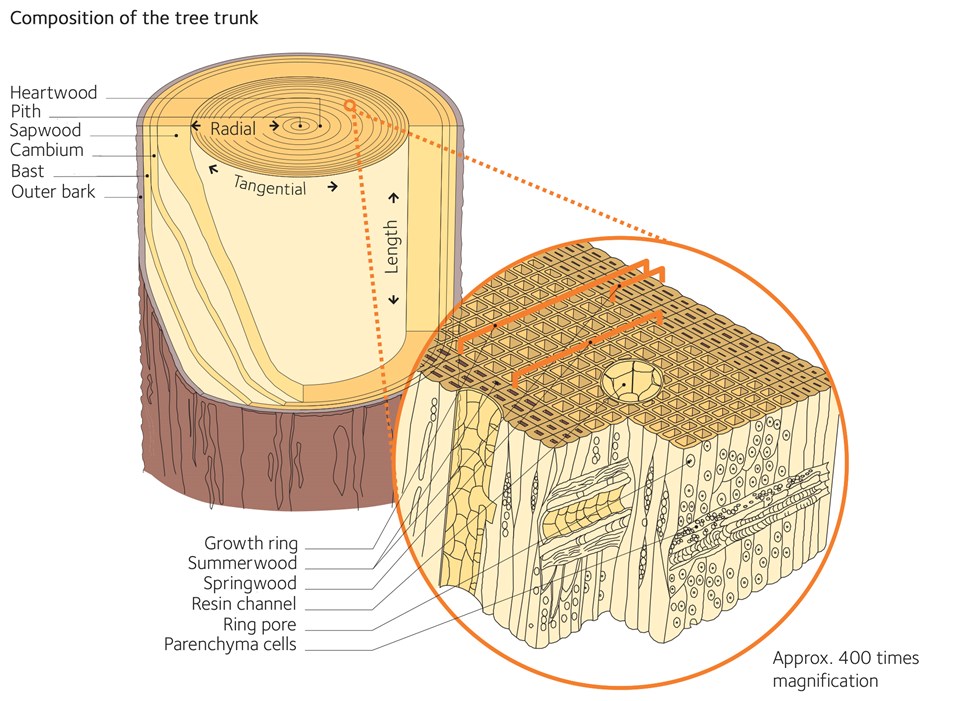

The composition and structure of the tree

Pines and spruces have a similar composition. In the centre of the stem’s cross-section sits the pith, which runs through the whole tree and terminates at the top with a bud. The pith is enclosed by the wood, which can be divided into heartwood and sapwood. The cells in the heartwood are dead and some have been clogged up with resin, which means that they can’t carry water and thus have a relatively low moisture content, 30–50 percent. The sapwood’s cells are also dead, except for about 5–10 percent, which are the nutrient-carrying parenchyma cells.

Since the sapwood’s cells are not clogged with resin, they are able to carry water and the soluble nutrients from the absorbent root hairs to the needles of the tree. The sapwood’s moisture content varies between 120 and 160 percent. Outside the wood lies the cambium, which is the stem’s growth layer. The cambium produces wood cells inwardly and bark (cork) cells outwardly. The cambium is encased with the bast (phloem), which is often referred to as the inner bark. This layer transports nutrients (carbohydrates) down through the stem and distributes them to the living cells in the tree’s branches, stem and roots. The bast is connected to the pith via medullary rays, which are living in the sapwood but dead in the heartwood. The outer bark encases the whole stem, providing protection from water loss and various parasites.

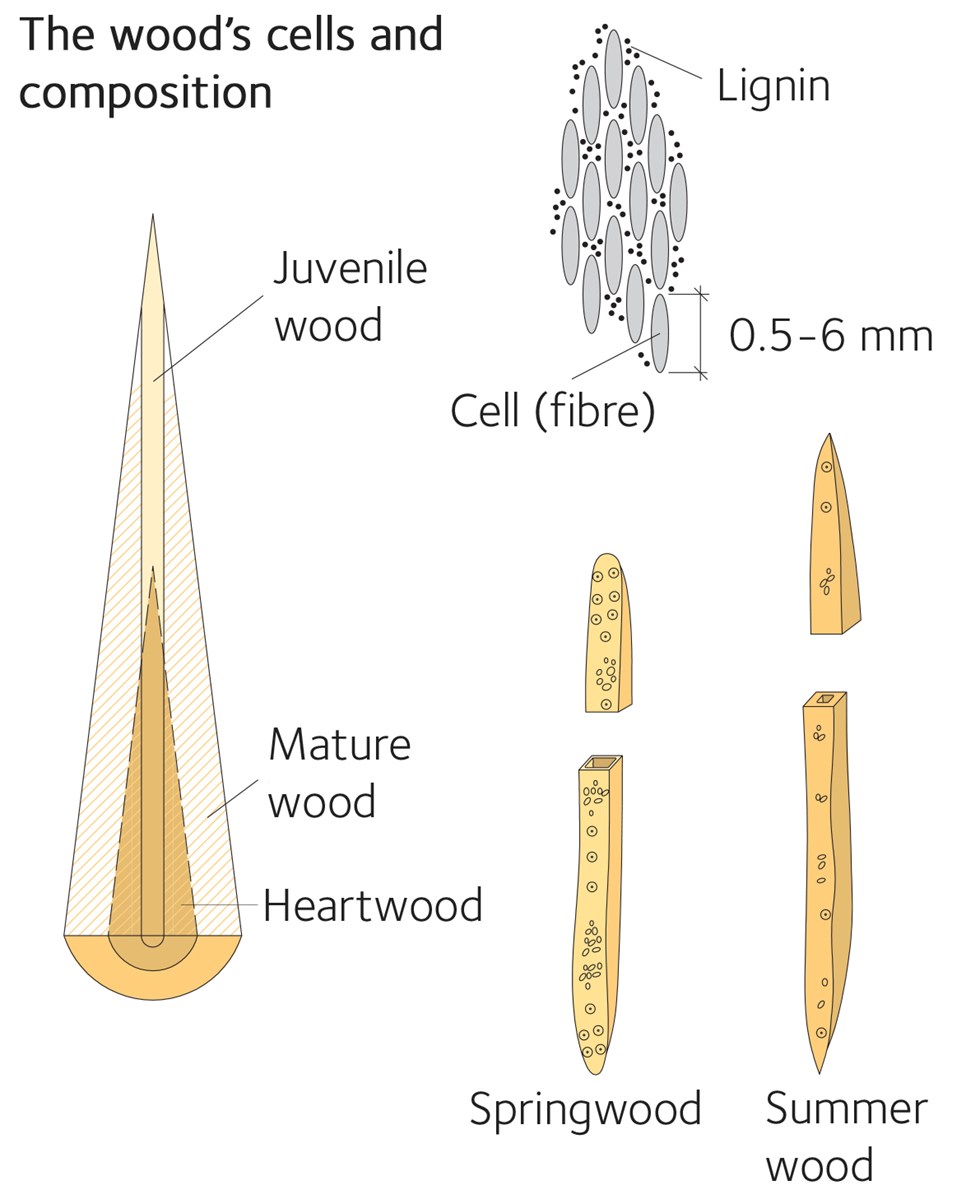

The conifer tree’s wood comprises 40–45 percent cellulose, around 20–22 percent hemicellulose and just under 30 percent lignin.

There are also 2–6 percent extractive substances in the wood. The vast majority of these are resin acids, fatty acids, carbohydrates and minerals (ash).

90–95 percent of the wood is made up of long, hollow cells, which the forest industry calls fibres. These fibres are about the thickness of a hair and vary in length between 0.5 and 6 mm. The other cells are shorter, with thinner walls.

During the growth season, new cells are formed in the cambium. The cells that are formed in spring and early summer are short and relatively wide, with thin walls. This means that the basic density is low, at around 300 kilos per cubic metre. The summer wood cells, which form during the summer months, are 20–25 percent longer and have much thicker cell walls than the springwood. The thicker cell walls mean that the summerwood cells are around three times heavier than the springwood cells, with a basic density of around 900 kg/m3. Due to the differences in density, the springwood appears as a lighter ring than the dark summerwood.

The density of the wood, a key factor for many technical properties of wood, is determined largely by the proportion of summerwood in the width of the growth ring. Judging the density based solely on the width of the growth ring is therefore misleading.

The way the growth rings develop is determined in part by the climate during the growth season. The growth rings therefore tend to be narrower and have thinner bands of summerwood in colder climates than in warm ones. As such, it is possible to see indicators of good and poor growth years, and how the conditions for growth have been affected by different silviculture measures. Growth improves after thinning due to better access to light and nutrients, and conversely growth can fall if a tree has grown too close to other larger neighbouring trees.

The width of growth rings and the proportion of summerwood varies within the stem.

In the inner part of the stem, in the juvenile wood near the pith, the growth rings are often broad with thin summerwood bands. The density is therefore low in the wood near the pith, compared with the mature wood further out along the radius of the stem. This is the case along the whole length of the tree.

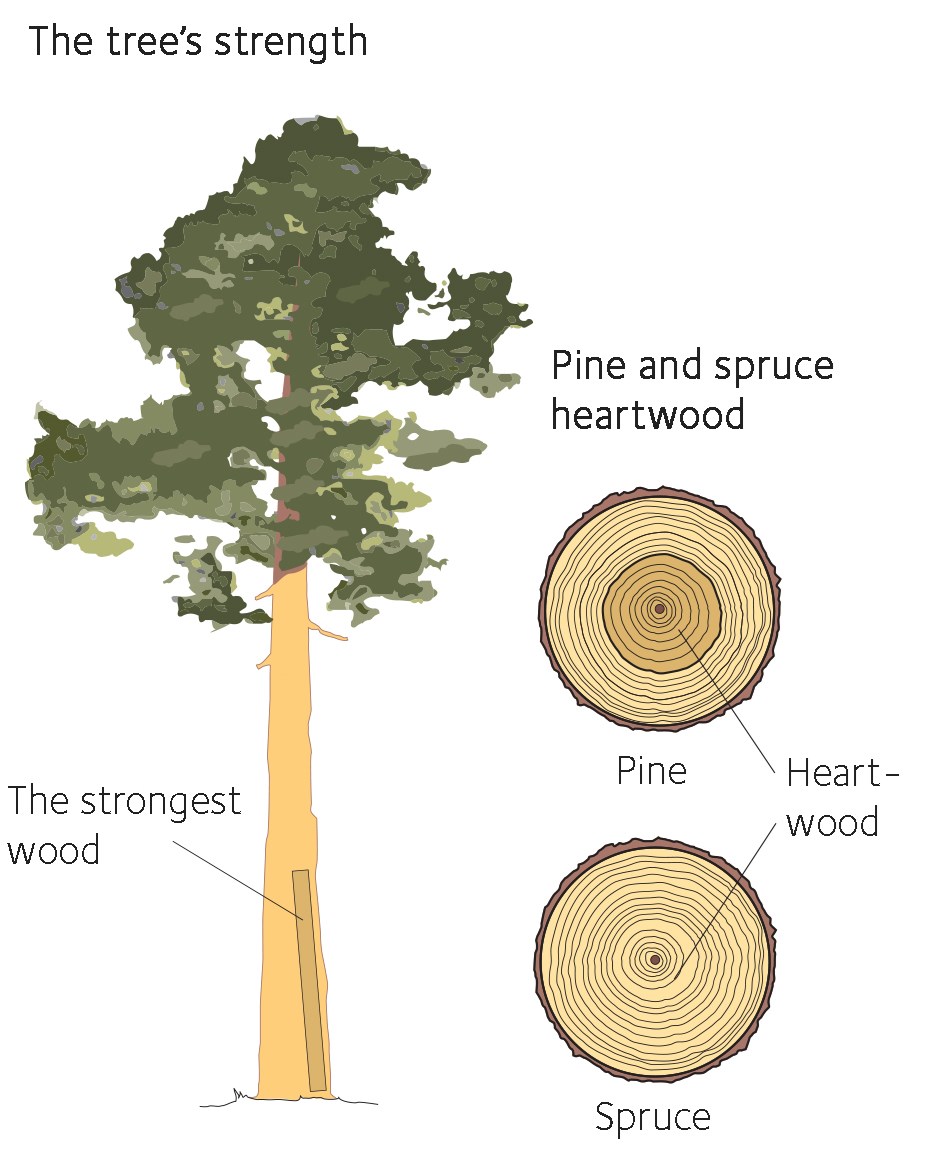

The growth rings are narrower, with broader summerwood bands, in the outer parts of the stem, particularly in the lower logs. The proportion of summerwood is thus higher, which gives the mature wood a higher density and strength. The lower parts of the stem need to be stronger to resist the stresses of wind and snow. The density is therefore higher in a butt log than in a middle log or top log.

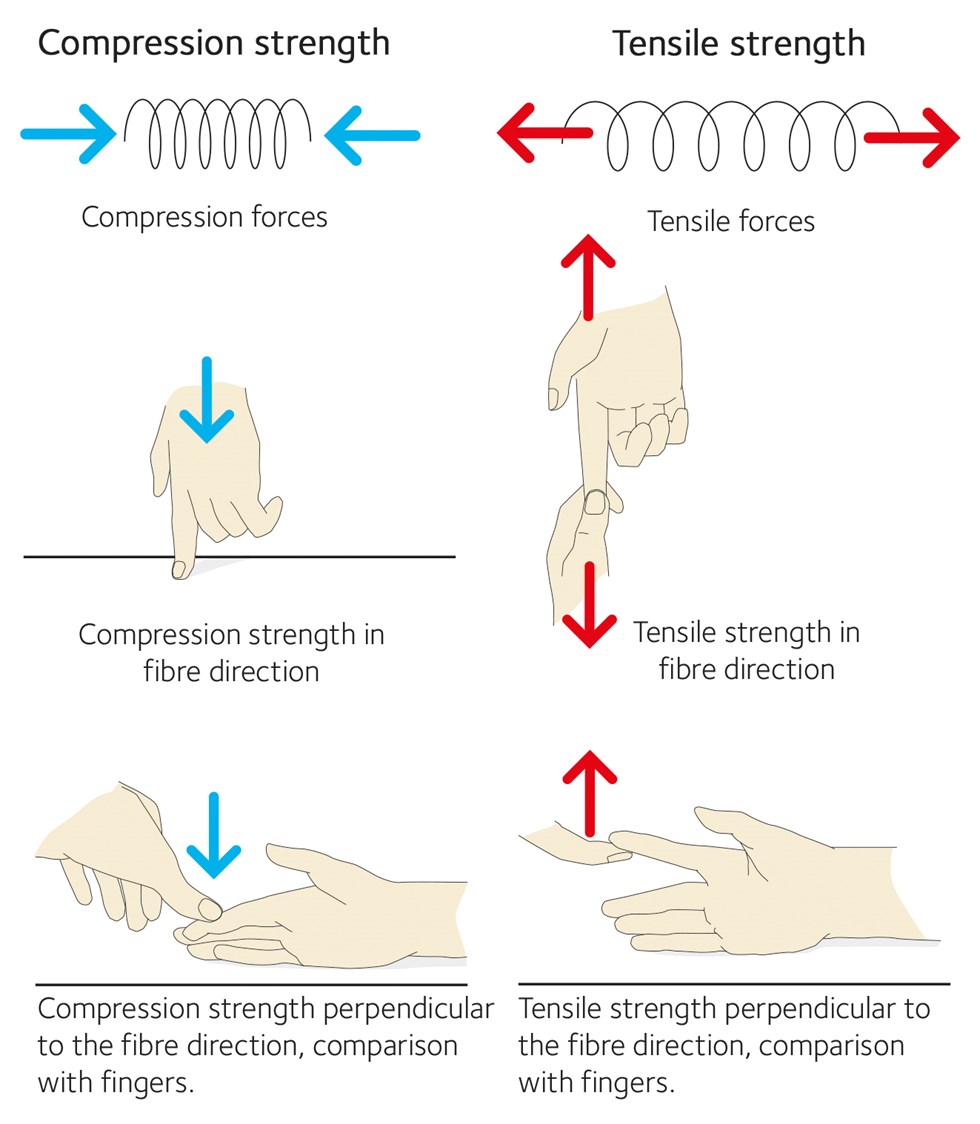

Strength

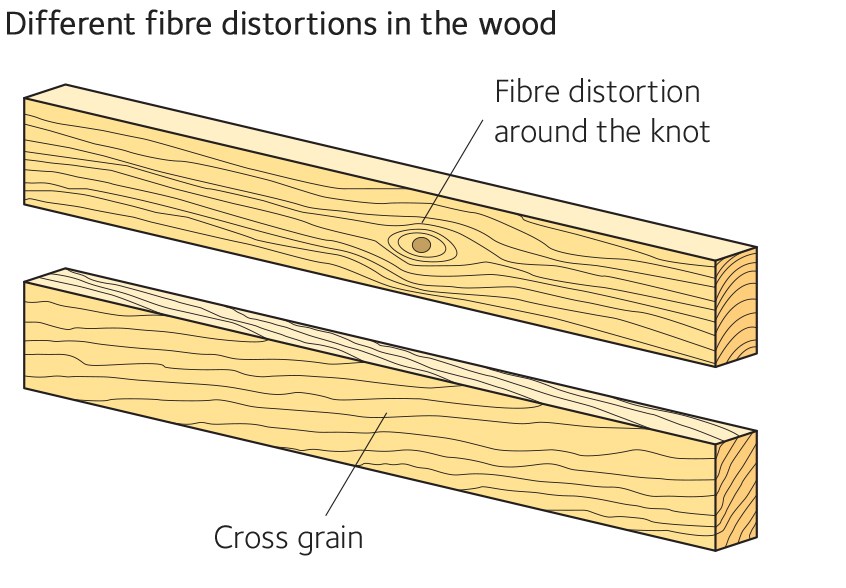

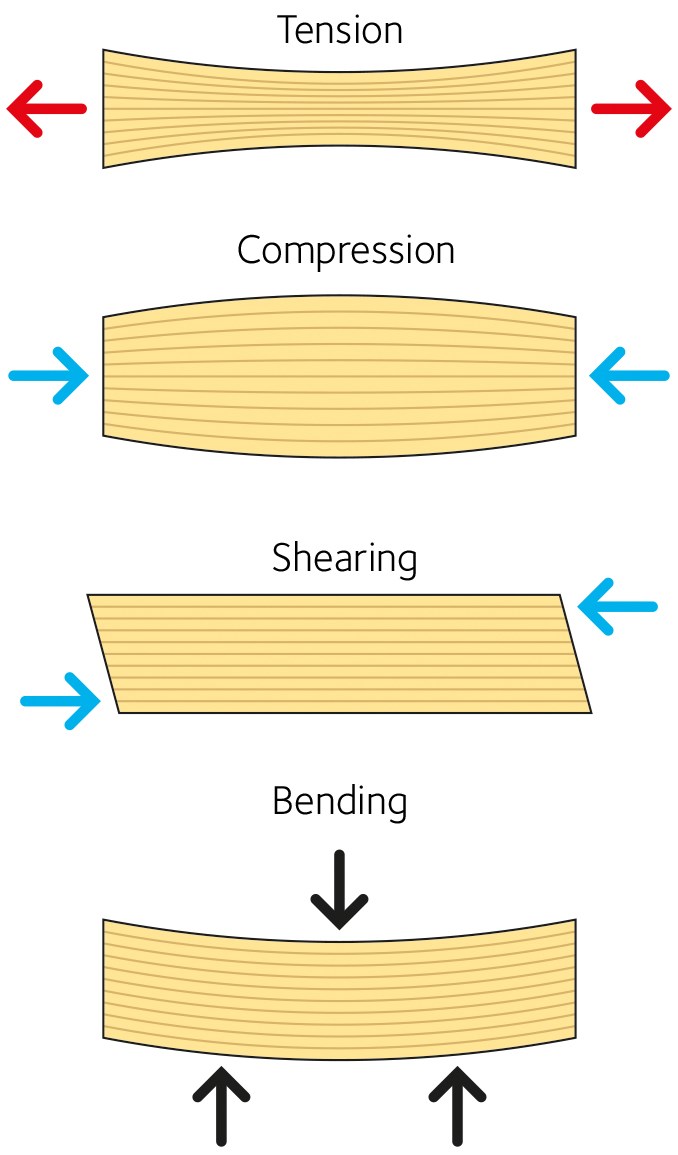

Wood is an anisotropic material, which means that it has different properties in different directions. For example, wood is considerably stronger in the direction of the fibres, i.e. following the length of the stem, than at right angles, across the grain. This is the case whether the load is caused by compression, tension or bending stresses in the wood.

The strength depends in part on the density of the wood and on how well the direction of the fibres matches the direction of the forces that arise when the wood is under stress.

The fibre direction deviates from the direction of the forces at knots and when the fibres are not parallel with the edge of the wood.

The strength is also affected by the moisture in the wood, its temperature and the period under which it is stressed. A dry piece of wood is stronger than one with more moisture, and colder wood is stronger than warmer wood. The longer wood is placed under stress, the more its strength reduces.

Fractures may be gradual or brittle. A brittle fracture is sudden and occurs without warning. A gradual fracture is preceded by some form of warning, such as major distortions or cracking sounds in the wood. Generally speaking gradual fractures, which account for most fractures in wood, are preferable.

The strength of the wood depends on how the stress occurs, there is thus the following correlation:

Table 12 Strength – Stress

| Strength | Stress |

| Compression forces | Compression strength |

| Compression strength | DragTensile strength |

| Bending forces | Bending strength |

| Bending strength | Shear strength |

The wood’s strength cannot be fully used up around the fracture limit, so lower levels of stress have to be chosen. This is due to the way the wood’s properties spread so widely, which means that safety margins have to be built in.

In terms of strength, pine and spruce are treated the same, and they are normally judged to have the same strength values:

- Compression strength is high in the fibre direction, with the grain, but much lower, around 1/6, across the grain.

- Tensile strength is high with the grain, but much lower, around 1/30, across the grain.

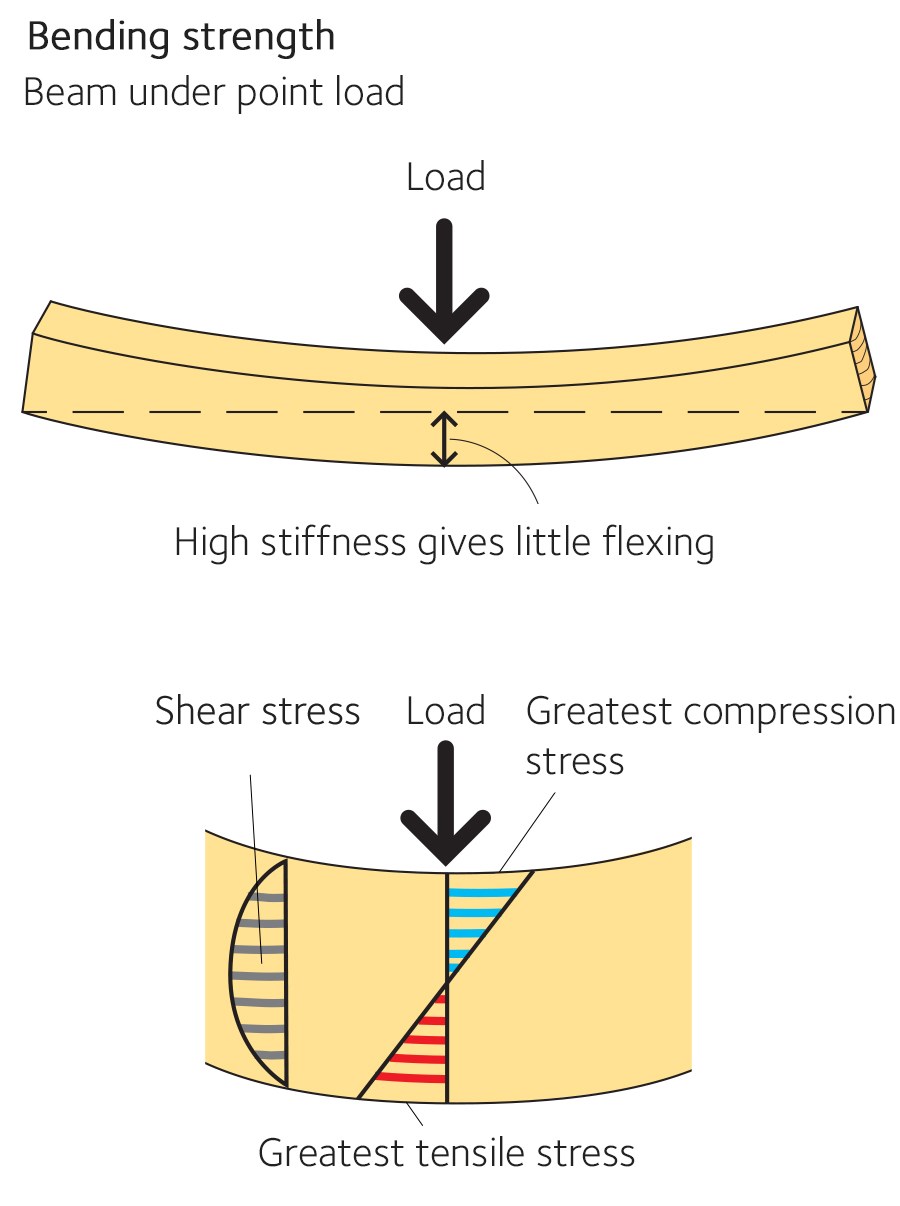

- Bending strength is usually measured with the grain.

- Shear strength is higher across the grain than with the grain, and so in most cases the shear strength with the grain is the critical factor, for example at the supported ends of a beam.

Stiffness and hardness may also be included in the strength properties. Stiffness is the opposite of bending or deformation. When a length of wood with high stiffness is bent, it doesn’t give very much, remaining quite straight instead. The degree of bending depends on the grain of the wood and on its modulus of elasticity. A high modulus of elasticity means high stiffness.

Hardness refers to the ease with which a surface is damaged by external pressure, for example heels on a floor or knocks on a table top. The hardness of wood is greater with the grain than against it.

End-grain flooring is hard and durable as the surface is entirely end-grain wood.

Apart from the direction of the fibres, the hardness of wood depends primarily on the density. In wood flooring, the springwood therefore wears more quickly than the summerwood. A wood with a high density should thus be chosen for flooring.

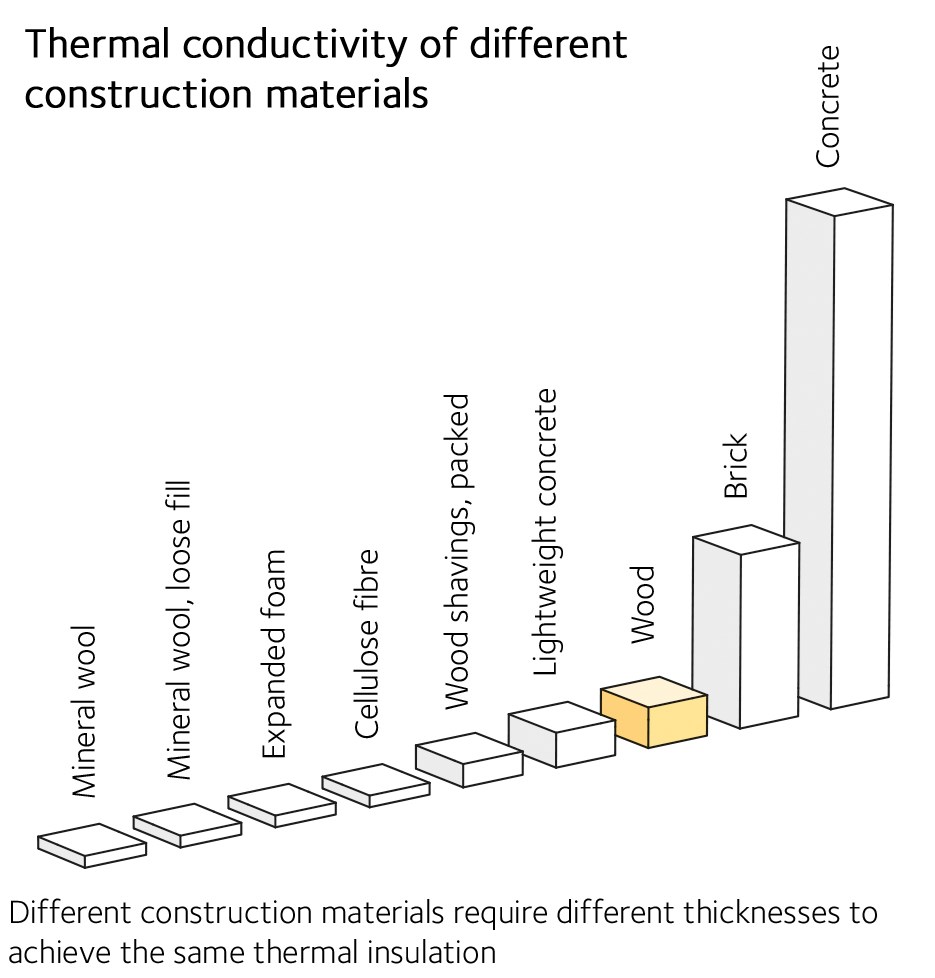

Thermal properties

Wood has good thermal properties and historically solid wood has been used as a thermal insulation material. Thermal conductivity is greatest in the direction of the fibres, and it increases with the moisture level and the density.

The thermal capacity of wood is relatively high at around 1,300 J per kg °C for absolutely dry wood.

The effective calorific value of pine and spruce as a fuel is 19.3 MJ per kg dry substance. Compare table 11 in this section.

Burning properties

Numerous factors affect wood’s burning properties, primarily moisture content, dimensions, density and fibre direction. The time until ignition can vary greatly and depends on thermal radiation, ventilation and the presence of a naked flame. The lowest thermal radiation for the ignition of wood with a naked flame is around 12 kW per cubic metre. Higher levels of thermal radiation are required for ignition without a naked flame. Wood cladding with a thickness of ≥ 18 mm (≥ 12 mm without air gap behind the wood cladding) meets class D under the European system. Burning wood only generates moderate amounts of smoke.

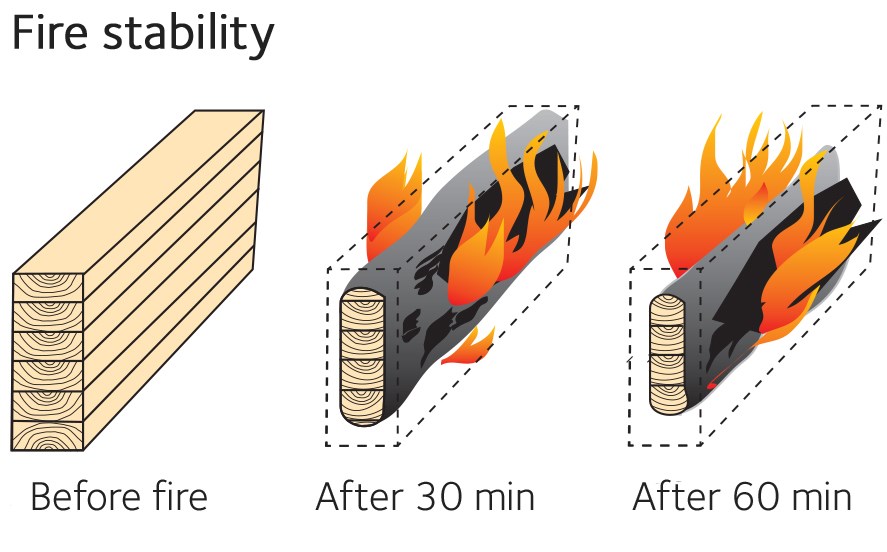

Wooden structures have good fire safety properties. Wood chars slowly and below the charred surface is normal wood, which retains its original properties. The charring rate is around 0.5–1 mm per minute. Larger dimensions and protection of the wood’s surface can make a wooden structure’s fire resistance higher.

The load-bearing capacity of wooden structures in a fire can be worked out mathematically, in line Eurocode 5 for example.

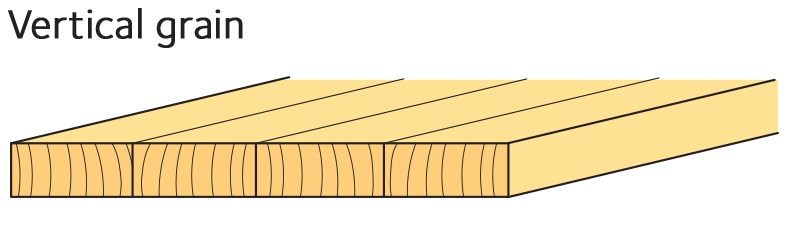

Edge-glued panels and glulam panels are usually made from wood with a vertical grain for good dimensional stability.

Edge-glued panels and glulam panels are usually made from wood with a vertical grain for good dimensional stability.